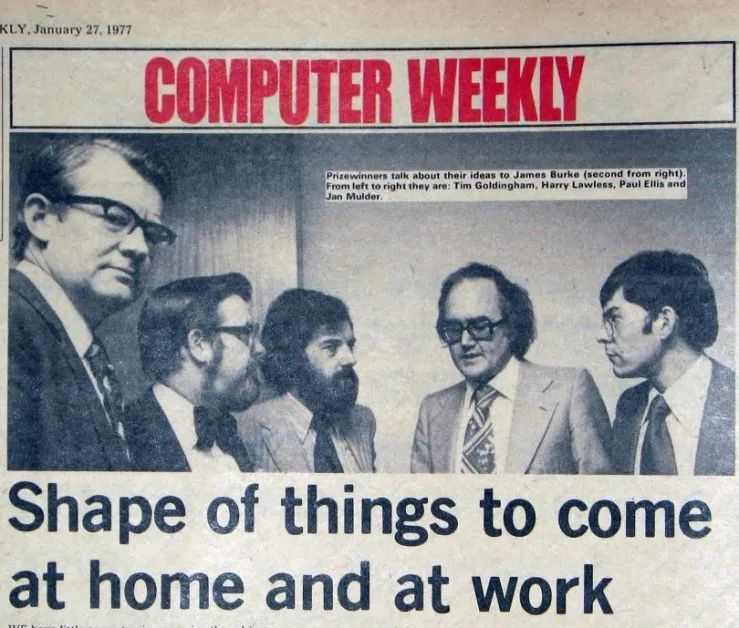

In 1976 when I wrote the essay below for a competition, it was already possible to link computers by telephone line, but an international structure, eventually called the Internet, wasn’t established till 6 years later. Its use was limited to academics and technical types keeping in touch, till Tim Berners-Lee invented the World-Wide Web, nine years after that. Bill Gates had started a small company the year before, in 1975, called Micro-soft (sic) but I didn’t hear of it till seven years later, as the supplier of PC-DOS. There were word-processors, but I’d never seen one. They were stand-alone dedicated machines. I worked for a cool software company called Zeus-Hermes (see ad below): our secretary made do with an electric typewriter, its ‘golf-ball’ had an italic font, just to show how trendy and devil-may-care we were. There were of course no mobile phones, let alone ones with ‘apps’. I had just bought my own first pocket calculator, a Casio. My essay talks about hierarchies of data and access via password, a state-of-the-art preoccupation at the time, which made the film TRON which came out six years later, seem dated.

I led a team in Zeus-Hermes which sold ‘mini-computers’ to small businesses. For around £60,000 we supplied a system packaged with about 4 visual displays, a printer and bespoke software written in Business Basic. Some personal computers were around, with little more than an operating system (CP/M) and the programming language Basic. The IBM PC didn’t arrive in the UK till about 1983. In 1978, a Japanese company, the Sord Computer Corporation, gave us one of their ‘microcomputers’ (basically like a PC as we know it today), hoping we’d write software for it and sell it to our clients. A member of my team wrote a game for it in a few lines of code, which kept us amused for hours.

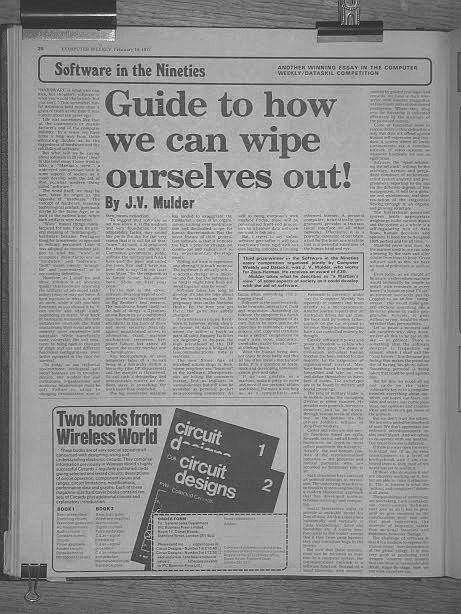

So that’s a bit of background. The prescribed essay topic was ‘Software in the Nineties’, and I went today to the National Museum of Computing in Bletchley Park to take photos and extract the following text.

“Hardware is what you can kick, but shouldn’t; software is what you would like to kick, but can’t.” This rueful definition held more than a grain of truth at the-time it was current about ten years ago.

Life was sometimes like that at the customer’s or manufacturer’s end of the computer industry. In a sense we have come a long way from those alienating doubts as to the ruggedness of hardware and the reliability of software. But what will we be saying about software in 20 years’ time? In this brief essay I have tried to take a “Martian’s view,” a wide-eyed non-partisan look at some aspects of society as it could develop with the aid of that peculiar modern thing called “software.” The word itself, we may be sure, takes its origin as the opposite of “hardware.” The concept of hardware, meaning technological artifact, goes back maybe to the Stone Age, or at least to the earliest time when such artifacts were bartered. “Ware” means things manufactured for sale. From its general meaning of “ironmongery,” hardware became Pentagon slang for armaments, as opposed to military personnel. Later it was adopted as convenient jargon to label the “ware” of computer manufacturers as “hardware” and “software”. “Soft” meant merely “intangible” and “non-material” as in my starting definition.

However, as I shall try and show, softness is an abstract qualify that hardware (meaning the artifacts of advanced technology,) may or may not have. A hard machine is what it is and no more, while a soft machine functions as you choose it to. It can evolve and adapt itself, responding to needs. Way back In biological evolution, the soft vertebrates overtook the hard crustaceans; their structure was innately more responsive and adaptable. While superficially more vulnerable, the soft creatures, by being open to changes of shape and size and different functional configurations, were better equipped in the race for survival. So today as our technical environment, ecological and social balances are in transformation, the models for our institutions, organizations and economic relationships must be soft. Failure to adapt to changing cirrcumstance, now as then, means extinction.

To suggest that software as we now know it is the medium and very foundation of this adaptability factor, may sound like pie in the sky for the very reason that it is still for all that, “ware.” As such, it is produced for those who can afford it. Commerce, government, public utilities, the military and NASA have paid the piper and called the tune. You and I have not been able to say “Let me taste your Ware.” for the response, as to Simple Simon, has always been “Show me first your penny.”

To the man in the street, software, meaning applied computer power, may have appeared as Big Brother’s best weapon. The mainframe beast itself, at the hub of things, a Tyrannosaurus Rex in its air-conditioned cage, has demanded tribute of its attendants in the form of more and more security. Security against unauthorised access to information, fraud, machine malfunction, terrorism, fire, power failure: but above all against the enemy number one—human error. Any incompetence, or even temporary lapse, of a human being in a hierarchy—the monster is threatened. To call such a demanding and unreasonable master an obedient slave is stretching the truth.

The big mainframe machine has tended to exaggerate the totalitarian aspects of an organisation, causing over-centralisation and diminished scope for human discrimination. But the worst feature of third-generation software is imposing too high a price on change, on continuous and radical, not to say experimental, developments. Writing software is expensive and altering it is more so. The hardware is actually soft—it accepts change in a microsecond, but the software is so hard it might have been soldered together wire by wire! Software takes too long to develop: it’s like the joke about the ten month waiting list for pregnancy tests on the National Health Service.

Tyrannosaurus-type hardware is, however, dying slowly in favour of data collection where the action is (such as POS, point-of-sale). Enquiry facilities are beginning to bypass the high priesthood of the DP department, Space is bridged by telecommunications, time is real-time.

The new Stone Age of inscribed silicon chips is here, where programs are “burnt-in” to the hardware. Microprocessors are hitting the consumer market, first as implants in various devices, but will soon be available as personal pocket data-processing computers. As well as being everyone’s own Machine Friday. these will be personalised front-end processors to whatever data network we want to link into.

But, I regret to say, unless software gets softer it will be a reactionary force, rigid with our own lagging concepts, a limiting factor when everything else is forging ahead. Software in the Nineties needs to be heuristic, interactive, fluid and responsive. According to folklore, the computer is a dumb beast, with no intelligence of its own. But to be more precise its capacities to remember, repeat, process, sort, copy and translate make a perfect complement to man’s own slow, inaccurate, unreliable, easily-bored, lateral-thinking brain.

What the human being does not enjoy he does badly and this all too often means mechanical tasks. It is a question of teamwork and developing cornmunication, give-and-take. If we can confide in a machine, make it privy to more and more of our personal affairs and foibles, the more it can help us, as a sympathetic and informed listener. A personal computer, heuristically programmed, provides a transactional interface to all other networks. Effectively, it is a powerful extension of our brain, a tool for the brain as a machine tool is a powerful extension of the human hand and eye. Research is currently under way (as Computer Weekly has reported) to connect the brain directly to a microprocessor. Another journal reports that an Australian drives his car from the back seat by walkie talkie: controls on the car respond to his voice. Merge the two and you have a car controlled entirely by thought. Clearly, software is power and power is freedom—to him who has it. But, since the dawn of civilisation, individual human freedom has been limited for the majority by the exigencies of group survival. Men have been forced to combine in hierarchies, take on roles, define themselves as members of castes. The archetypes are to be found in military and feudal groupings.

The king or military leader is in modern terms the managing director or prime minister. He presides over generals, barons, directors and so on down, through various levels of executive. At the bottom are the private soldiers, serfs or shop-floor workers. Castes and roles are not merely functions based on skills. Rewards, status, and all kinds of limitations on freedom must reflect position in the hierarchy. Actually, the real bottom consists of the institutionalised outcastes—the prisoners and mental patients, who are accorded no functional role at all. Such structures have survived all political attempts at revolution. The underlying reason is to be found in systems engineering, a modern theoretical approach that has developed midway between sociology and computing. Social hierarchies exist to provide a workable model for flow of data. All that takes place horizontally and vertically is ‘data transactions.’ Love and friendship are of course non-functional to the model; except that if they cross caste barriers they may constitute bugs in the system.

But now that these transactions can be mirrored in real-time by a computer system, the communications network is a software function. Instead of a social hierarchy, with seniority marked by graded privileges and rewards, we have a data hierarchy, with humans plugged in as functional units of distributed intelligence. Where they plug into the hierarchy is indicated effectively by the structure of the password system. Caste or functional level of responsibility is thus defined in a way that does not offend against human self-expression and freedom. A system where all levels communicate via a common network of video screens, or whatever hardware we use, is egalitarian.

Software, the “spirit inhabiting the network” will not be the arbitrary, narrow and prejudiced construct of technicians, called system analysts and programmers, reporting to the top via the different degrees of line management. It will be a genuine and spontaneous, real-time, resolution of the exigencies flowing through it, an organic and growing structure. The hierarchical password system lends appropriate weightings to the various inputs and the system as a whole is a self-regulating mix of data flows, human decisions and opinions. It need not be designed 100% perfect and for all time—mankind was never thus. As the mariner used to, we can take a bearing by the stars and alter course from hour to hour.

Given software such as this, we have no need of politicians as such at all. Even today, as we should all be aware, a referendum machine would technically be simple to install, with terminals in every home (“a button on your TV set” as someone succinctly put it).Coupled to an on-line “swingometer,” this would make general elections something like a monster phone-in radio programme. Policies, it goes without saying, would be elected, rather than personalities. Let us pause a moment and ask ourselves why, deep down, we feel all this to be pie in the sky—at present.

There is something that the software designer is frequently up against, which I shall call the “trust barrier.” It is the same gut feeling that makes the primitive shy of having his photo taken. Something personal is being taken that could be used against him. But for this, we could all lay our cards on the table, voluntarily key in to a computer network everything about ourselves, our hopes, our fears, our sales and wants, our curriculum vitae, our opinions and creative ideas and in return get some of the answers. But we don’t trust the others. We are not a united brotherhood of man. We don’t appreciate our enforced interdependence on this small planet. And we refuse to co-operate with one another. Our consciousness is deficient. If there is a way open for every individual one of us, to raise consciousness to a level of brotherhood, and I am convinced there is, then most of the world has yet to realise it. Of those who do realise it and are sincerely working on it, few yet are able to voice it effectively. This at bottom is what the “privacy and computers” debate is all about. The possibilities of technology are overtaking, have overtaken, our consciousness. Software can’t give us all it has to give, until we give ourselves to the consciousness pool, and until that pool represents the interests of humanity rather than sectional interests and exploiters, however “benign.”

The challenge of software is to be a medium to express the transactional interdependence of the global village. It is also very good at producing total weapon systems and models that can show us in considerable detail, stage by stage, how we can wipe ourselves out.

This was wonderful! A glimpse at a “Vincent” from yesteryear AND a look at a part of your life that we don't hear too much about.

As for the essay, it seemed quite ambitious in its scope…and indeed, “prophetic”, as you say. I must confess, I tried to keep pace with it as best I could, but at some points it all just went clean over my head. I'd debate the finer points of software, but I'm clearly out of my league AND my weight class on this one.

LikeLike

Sorry about that Bryan. I had not foreseen the possibility that 35 years later I might republish it for a more general audience. In fact until I read it, after the trip to the museum to photograph it, I felt embarrassed about it, and thought that I might at best find a quote or two worth repeating.

In the event, it wasn't too bad, though you'll note the obligatory dose of cultishness injected into the last paragraph:

“Our consciousness is deficient. If there is a way open for every individual one of us, to raise consciousness to a level of brotherhood, and I am convinced there is, then most of the world has yet to realise it.”

That's the main bit that makes me cringe now.

LikeLike

I just took those sentiments in the closing paragraph as signs of a more youthful idealism. But I have only to look at my own old notebooks to sympathize with how cringe-inducing those kinds of things can seem in hindsight, years later.

LikeLike

Sounds like there needs to be a great leap of faith on the part of humankind and I'm too cynical to believe this will ever happen. For one thing, people enjoy their autonomy too much.

I've always liked the idea of having my brain connected directly to a computer, and think this sort of action might facilitate a leap of faith eventually and lead to more of a sense of brotherhood.

This is such a very intriguing post. I'd love to hear more.

LikeLike

Yes, Bryan, but it could be a great deal worse!

Rubye thanks for your comment. You'd love to hear more? Perhaps my latest post will grant your wish!

I've been looking over at your blogs too. Both highly intriguing. I shall return soon!

LikeLike

Very interesting, entertaining, and informative time capsule, Vincent. I'm not versed in the intricacies of software, but it's fascinating to see the concerns you brought up and where we are today. As far as the cost factor goes, it makes me see how Apple has worked with the software/hardware issues to some degree and people seem to trus Apple–at least that's my impression. Your commentary on systems thinking caught my interest. We are all indeed systems within systems working together with our own place within the system. You “voice” is still very much the same as it was in 1976.

I may be wrong, but in 2012 it seems we trust software too much, myself included. Thanks for sharing. How wonderful to be able to visit your piece in a museum!

LikeLike

Don't know how I missed this post. But I've been on and off for the last few weeks with other things.

Your descriptions put me in mind of the movie “Colossus-The Forbin Project” where the first huge mainframe computer actually takes over the world in a very “1984” type way.

And I'm with Bryan. I followed the monograph avidly but alot of your thoughts, even back then, were way out of my weight class.

LikeLike

Rev, the museum which houses an archive containing my essay also contains the actual real-life Colossus computer. It's closed to visitors at present because they are refurbishing it–presumably to get it working again, so it can take over the world. I rather think it won't be switched on all the time, as it's made of thousands of valves, which must require megawatts to warm up, and give out a lot of heat.

Next time I go, I'll report and bring back some photos–when the refurbishment is complete.

LikeLike

I've done the usual 2-minute research & compared the computer mockup used in the movie you mention with the real-life Colossus in Bletchley Park, and they are not the same animal.

See for example the real thing, built in England in WW2, versus the Hollywood version, using parts of the IBM 1620, released in 1959.

LikeLike

That always throws me. Valves. Makes me think of a steampunk computer. And then my mind just runs away with me.

LikeLike

Well it was a steampunk computer, unless I have the definition wrong. But I haven't seen the movies that you may be referring to.

LikeLike

I am trying to remember you – I worked for Zeus Hermes too…

Jacqueline (formerly Ebbutt)

LikeLike

Well, I remember Charlie Ebbutt very well. You are surely related to him, but I don't remember any other Ebbutt on the payroll! Tell me more, please. When did you work there?

LikeLike

Anyhow, you can see me in profile at the right of the picture above.

LikeLike

I am trying to pull the cobwebs out of my memory – I wish I could say I remember your face and I am terribly sorry I can't. I was Jacqueline Lee when I worked at ZH and married dear Charlie after I left. I worked from Cork Street and Moscow Road. Incredibly interesting times. I was probably more into pattern recognition, cybernetics and epistemology at the time. I went on to work for Lloyds Bank and then as a professor of IT at Southbank – now I'm 'retired' and run a publishing company.

LikeLike

Ah, it was Charlie who gave me the job. I was at Capper St and then Tottenham Court Road, always as a project leader on commercial systems. Clients were Ocean Trading (Southampton), Datakeep (London East End) – can't remember all of them straight off.

So you are “retired”? I am retired without the quotes, having turned 70 this year, though I still do some IT work occasionally.

Yes, they were such interesting times! I wish I had stayed longer at ZH but it seemed to change after the move to Tottenham Court Road …

I suppose Charlie is no longer with us?

LikeLike

Were you with ZH at the time of the Autonomics crash? Did you know Zac? I loved your article – we had a test harness at Lloyds in the 80s that took 9 months… not quite 10, but there you are – talk about turning on a 6 pence. Before ZH I worked on Atlas – there was a sign up for Christmas parties – No Canoodling in Core Store! The thermionics just couldn't take the heat…

LikeLike

[…] yesterday reading my own essay written 35 years ago, I was curious to know what would have beaten it into third place. I remember at the time having a […]

LikeLike

[…] also this previous post and also my own essay for the same competition hosted by Computer […]

LikeLike