Today is the 70th anniversary of Desert Island Discs, a BBC radio programme in which celebrities are interviewed about their life, interspersed with their personal selection of eight gramophone records. At the end, they are invited to choose one book and one luxury to take along to the desert island on which they are to imagine themselves marooned. They are always reminded that the Bible and Shakespeare will be provided in any case. I’ve never given thought to my book choice; but when they start inviting nonentities on the programme, and my turn comes up, I’ll be sure to request that my Bible is the Ernest Sutherland Bates edition: The Bible Designed to be Read as Literature.

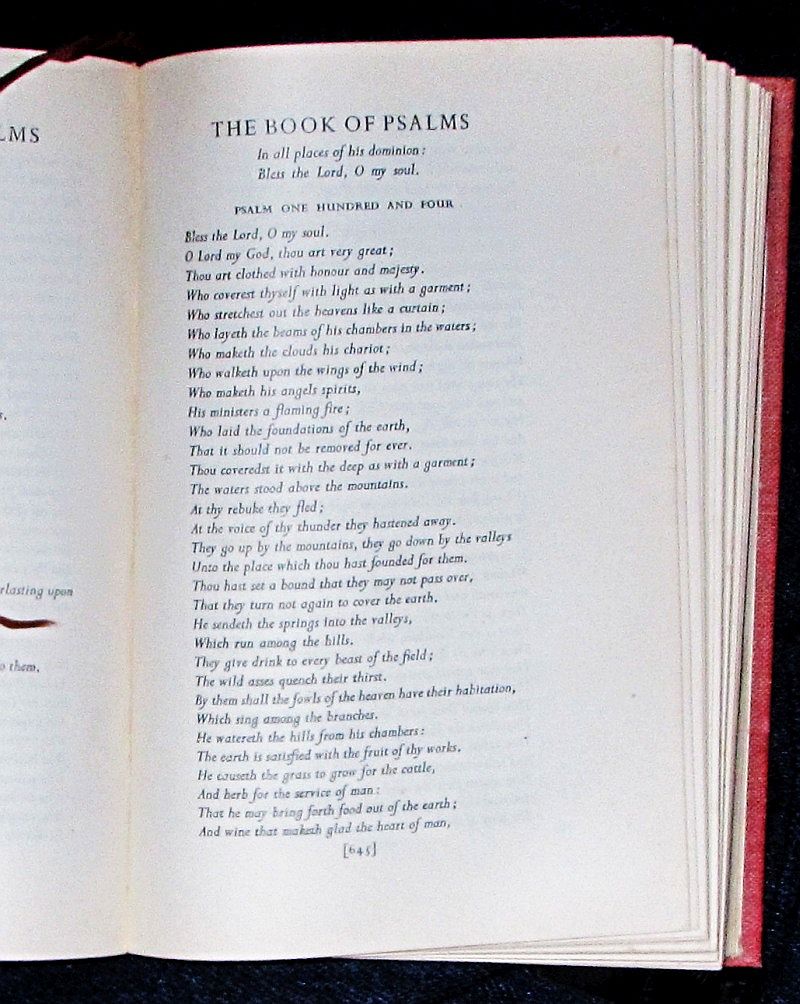

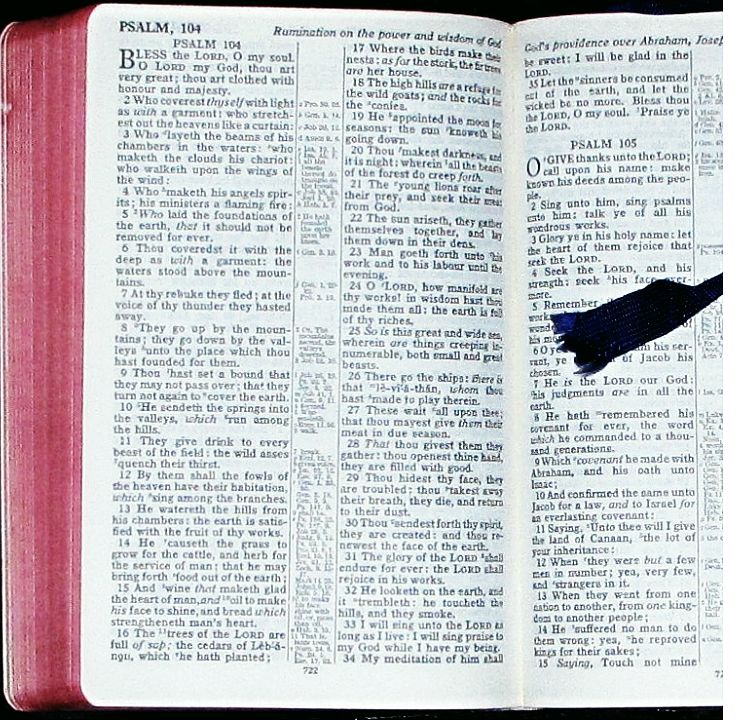

No doubt this is partly nostalgia. I was introduced to this edition at boarding school, aged ten, and learned the Old Testament stories through it. The text is from the King James Authorised Version, sonorous and poetic. Typographically it’s laid out so as to distinguish prose and verse. It’s not defaced with columns, notes, references and verse numbers; but as a regular book with chapters. Each Bible book is prefaced with a short editorial piece putting it in historical context and explaining the intention of its authors. Here are the sacred tales and songs of the tribe, this diaspora loosely known as the Western World. So this book is a ritual object for me, to read, to hold, to have it handy as required. I have an old family bible too, not my family particularly, but it has some thick pages between the Old and New Testaments headed Family Register, with spaces for Parents’ Names: Husband ….. Born ….. Wife ….. Born ….. Married ….. . The next pages are headed Births, Marriages and Deaths. None of these have yet been filled in. I bought it second-hand, and as I often do with books, patched up the spine & undertook minor repairs as needed. I keep this by my side too, for it’s in the conventional two-column format, divided into Book, Chapter, Verse, which you need in order for example to check the context of a biblical quotation.

No doubt this is partly nostalgia. I was introduced to this edition at boarding school, aged ten, and learned the Old Testament stories through it. The text is from the King James Authorised Version, sonorous and poetic. Typographically it’s laid out so as to distinguish prose and verse. It’s not defaced with columns, notes, references and verse numbers; but as a regular book with chapters. Each Bible book is prefaced with a short editorial piece putting it in historical context and explaining the intention of its authors. Here are the sacred tales and songs of the tribe, this diaspora loosely known as the Western World. So this book is a ritual object for me, to read, to hold, to have it handy as required. I have an old family bible too, not my family particularly, but it has some thick pages between the Old and New Testaments headed Family Register, with spaces for Parents’ Names: Husband ….. Born ….. Wife ….. Born ….. Married ….. . The next pages are headed Births, Marriages and Deaths. None of these have yet been filled in. I bought it second-hand, and as I often do with books, patched up the spine & undertook minor repairs as needed. I keep this by my side too, for it’s in the conventional two-column format, divided into Book, Chapter, Verse, which you need in order for example to check the context of a biblical quotation.

Though no Christian, I nevertheless treat these volumes as ritual objects, sacred spaces I can enter. It is right to have the tales of one’s own people, as every tribe and tradition does. It’s absurd to ditch them because we don’t believe in them literally, or in any religious way.

Though no Christian, I nevertheless treat these volumes as ritual objects, sacred spaces I can enter. It is right to have the tales of one’s own people, as every tribe and tradition does. It’s absurd to ditch them because we don’t believe in them literally, or in any religious way.

The English version of the Sutherland Bates edition has an introduction by Laurence Binyon, revered for his poem “For the Fallen”, commemorating casualties of the Great War 1914-18. And in this introduction he commemorates a lost tradition:

Some time about the end of the last century I remember waiting for a train at a little country station; and I was approached by an old shepherd in a smock-frock who, I learned, was making the alarming adventure of travelling by train (to the next station) for the first time. We fell into talk, and as he told me of his frugal life and the contrast between present conditions and those of his youth, when there was never enough to eat, and he had “neither home nor habitation,” I was struck by the Biblical character of the speech in which his thoughts seemed to find their natural expression. The Bible probably was the only book he knew; its language had soaked into his mind and fitted all the needs of his ancient solitary calling…. His world is gone, his language is heard no more.

Now I turn to the middle of the book, to “The Book of Psalms: an anthology of sacred poetry”; and find Psalm 104, which blesses the Lord for this earth in such tender detail that it provides nourishment for the soul, quite independently of mere religion. Nourishment almost literally, for I can imagine it keeping someone alive in extremis, when no other succour is yet available; filling a gap left by humanism, science and hope for progress.

Bless the Lord, O my soul.

O Lord my God, thou art very great;

Thou art clothed with honour and majesty.

Who coverest thyself with light as with a garment;

Who stretchest out the heavens like a curtain:

Who layeth the beams of his chambers in the waters;

Who maketh the clouds his chariot;

Who walketh upon the wings of the wind;

Who maketh his angels spirits,

His ministers a flaming fire;

Who laid the foundations of the earth,

That it should not be removed for ever.

Thou coveredst it with the deep as with a garment;

The waters stood above the mountains.

At thy rebuke they fled;

At the voice of thy thunder they hastened away.

They go up by the mountains, they go down by the valleys

Unto the place which thou hast founded for them.

Thou hast set a bound that they may not pass over,

That they turn not again to cover the earth.

He sendeth the springs into the valleys,

Which run among the hills.

They give drink to every beast of the field;

The wild asses quench their thirst.

By them shall the fowls of the heaven have their habitation,

Which sing among the branches.

He watereth the hills from his chambers:

The earth is satisfied with the fruit of thy works.

He causeth the grass to grow for the cattle,

And herb for the service of man:

That he may bring forth food out of the earth;

And wine that maketh glad the heart of man,

And oil to make his face to shine,

And bread which strengtheneth man’s heart.

The trees of the Lord are full of sap,

The cedars of Lebanon, which he hath planted,

Where the birds make their nests;

As for the stork, the fir trees are her house.

The high hills are a refuge for the wild goats,

And the rocks for the conies.

He appointed the moon for seasons;

The sun knoweth his going down.

Thou makest darkness, and it is night,

Wherein all the beasts of the forest do creep forth.

The young lions roar after their prey,

And seek their meat from God.

The sun ariseth, they gather themselves together,

And lay them down in their dens.

Man goeth forth unto his work

And to his labour until the evening.

O Lord, how manifold are thy works!

In wisdom hast thou made them all;

The earth is full of thy riches.

So is this great and wide sea,

Wherein are things creeping innumerable,

Both small and great beasts.

There go the ships;

There is that leviathan, whom thou hast made to play therein.

These wait all upon thee,

That thou mayest give them their meat in due season.

That thou givest them they gather;

Thou openest thine hand, they are filled with good.

Thou hidest thy face, they are troubled;

Thou takest away their breath, they die,

And return to their dust.

Thou sendest forth thy spirit, they are created,

And thou renewest the face of the earth.

The glory of the Lord shall endure for ever;

The Lord shall rejoice in his works.

He looketh on the earth, and it trembleth;

He toucheth the hills, and they smoke.

I will sing unto the Lord as long as I live;

I will sing praise to my God while I have my being.

My meditation of him shall be sweet;

I will be glad in the Lord.

Let the sinners be consumed out of the earth,

And let the wicked be no more.

Bless thou the Lord, O my soul.

Praise ye the Lord.

And it is heartening to find, in Binyon’s Introduction, from which I’ve already quoted above, this passage, which could itself have been inspired by Psalm 104:

It was DeQuincey, I think who noted in the precept ‘Let not the sun go down upon your wrath’ something characteristic of the literature of the Bible; namely, the seeking for a harmony, a correspondence, between the actions of mankind and the larger movements of the universe in which man’s life is set. And I think that this is one thing that may especially impress the mind in reading Hebrew poetry. There is no description of things for their own sake; they are vividly seen, but all things are related to one another; we are made aware of them all—the mountains and the streams, the vineyards, the olives, the desert places, the sheep and cattle, the wild ass and the lion in the wilderness, the tender grass, the rocks, the sea and the ships upon the sea, the fishes under the water, the stars, the rain, the wind and in all this world men moving and going about their business, acting, suffering and rejoicing; all these are related to one another because united by the presence in the poet’s consciousness of the pervading power of the invisible Creator. A modern reader may have quite other ideas about the constitution of the universe, a quite different approach to it; but he will hardly deny that it is a living and mysterious whole; and through this profound conviction of the pervading, eternal spirit, touching all life with a kind of glory, Hebrew poetry has a grandeur of horizon together with a kindling warmth and passion which we find in no other poetry with the same constancy or to the same degree.

Having called myself “no Christian” I’d soften that and call myself a lay sympathizer, who doesn’t go to church, doesn’t believe that Christ died for his sins, nor in an after-life; is agnostic (as he thinks everyone has to be, really) about the existence of God. He likes the idea of Christianity, especially a particular part of it: in my case the most inclusive and doctrine-free form of Anglicanism. He sees his parish church as a bastion of tradition, a community centre, a rallying-point in times of war and crisis. He believes in the idea of an ancient culture that’s kept alive. He’s unmoved by all the controversies and hatreds, the extremists and fundamentalists on both sides of every divide.

And he doesn’t take it too seriously. In summary, he sees the Bible as literature.

LikeLike

I think I would usually fall under the category of “lay sympathizer” as well. I find the stories and the mystique of Christianity very appealing, and I admire Christ as a character as well as a person. I believe in his idea, which I don't think has been adequately understood by many Christians. It has been taken too literally, and yet not literally enough at the same time. I believe it truly could save the world, but not in the sense these people think. (That sounds cryptic, but it would take much more than a comment to explain. I have touched on it already in things like that Christmas Post – both the dream and the essay!)

Oh, but then there are those other days, when I hear about things like Ken Ham and his Creationist Museum, when the Fundamentalists here in America are elbow deep in someone else's business, when some jackass like “Joe the Plumber” says something stupid like God will protect him as he travels the Middle East when “God” hasn't seen fit to protect so many others in that region, and my heart and mind are…not so open. I know that I should separate the people from the religion, but there are days when it's hard not to feel that the people are a product of the religion.

Maybe we could start a new church of “lay sympathizers” who don't really believe in anything substantial, who start no wars and organize no protests for our creed, but who merely hold on to hope and toast beautiful sentiments and dream of old and ancient stories ;D

LikeLike

“…when they start inviting nonentities on the programme…”

^This made me smile as well.

LikeLike

I don't mind helping start a new church, “of the Latter-Day Sympathizers” perhaps. But I wouldn't want to join it. Thought of writing to join David Abram's “Alliance for Wild Ethics”. But then I thought “Uh? Why would I do that?” Am already a member of the human race, and a loyal subject of the Animal Kingdom. And when the nonentities go marching in, I want to be – in – that – number.

LikeLike

Bryan, I've appended a new 'Postscript' at the bottom of the post.

LikeLike

Yes, I like that postscript.

What strikes me as “characteristic” of the Bible (and perhaps it's related to this postscript) is how present the realm of God and Heaven is to the Earthly realm in which the stories are set. And yet, at the same time, God and Heaven are not quite of this Earth as the gods of Mt. Olympus or the Egyptians gods were. Rather, it all exists in another dimension of some sort, just slightly out of step with our own, the division between them paper-thin. God, quite regularly, either talks directly to people or reveals himself in unmistakable signs and wonders. Cloaked angels frequently show up to intervene in human affairs. There's never any question about these things. It's simply “God spoke to so and so, and told them to go forth to such and such a place.” It's not even like, Abraham heard a voice and believed it was God. It's just presented as straight-forward fact. The matter of doubt rarely ever enters the picture. It's just will they listen to God or won't they.

This implication adds up to an all-pervading subtext which creates a certain world, or a certain view of the world within the text. And I think that's what Christians find so appealing. The idea of Heaven and Earth in such intimate contact, just a breath away from each other. I think they try to view the modern world in which we live in this same light, looking for signs and wonders and the working of God's Will woven tightly into Earthly affairs.

LikeLike

Your latest comment, Bryan, really got me thinking, even to the point of planning out my next post, on the subject of The Cult: being in the world but not of it, by living in a bubble – an almost invisible membrane which protects you from everyone else's wickedness, but most of all from the seeds of Doubt.

For if we turn Belief on its head, what do we get but shying away from Doubt?

For in Nature there is Chaos, by which I mean all kinds of stuff, no clear pattern, just impressions. Eagerly we learn to “join the dots” (as in those children's drawing puzzles), to make sense of all the phenomena, for then we have power over the apparent randomness.

For surely there is a perceptible pattern. It used to be the role of culture – of civilization – to set out the pattern, enabling us to live in harmony. But that goes back to the time when civilizations lived mainly behind their own frontiers.

If we are to believe the historical tales in the Old Testament (I think we would do far better to read between the lines, and draw our own conclusions), we see that doubt was uncommon. Members of a different civilization, i.e. tribe, are conquered or put to the sword. No one says “Maybe their gods are more credible than ours”, or perhaps they do, but the tellers of the tales are not amongst them. The tellers of tales are free to describe them as “the ungodly” and rail at their wickedness constantly. And since this goes on a great deal in the Old Testament, we may be infer that there was a lot of scepticism, free-thinking and unorthodox living going on.

My thoughts are undeveloped on this. But your words above help me understand this ferment of religious intolerance, from both sides, that we are experiencing; especially given that it is no longer fashionable to put your enemies to the sword for failing to worship the same God, and our tribes don't stay minding their own business within their own time-honoured lands (did they ever?) but mingle indiscriminately under the same jurisdiction.

So a great deal of defensive effort has to be put into keeping the membranes of culture and belief impermeable against doubt. On both sides.

An attitude which leaks out into politics as well. In America. Most of what I've written in this comment is an attempt to understand America. Not to mention my own 30 years in a cult. I really do hate to mention that.

LikeLike

'No one says “Maybe their gods are more credible than ours”, or perhaps they do, but the tellers of the tales are not amongst them. The tellers of tales are free to describe them as “the ungodly” and rail at their wickedness constantly. And since this goes on a great deal in the Old Testament, we may be infer that there was a lot of scepticism, free-thinking and unorthodox living going on.'

Yes, exactly, my friend! If someone were to somehow pluck you or me out of time and drop us into the period of The Old Testament, we would find a world (at least in our eyes) much like our own, with all the same doubts and uncertainties. We would say the Hebrews believe this, the Persians believe that, and Babylonians believe in…and so on, just as we do when look at all the diverse religions today. We would find various people praying and moaning and rolling in the dust for their gods but we would never find the gods themselves, only the same blue sky and twittering birds. The Bible is not written from such a perspective – nor, of course, could it be, nor even would it have been, if such a thing had even been possible. It's a document of belief, so confident in that belief that it doesn't even bother to declare itself as such. It is written entirely within its belief structure. God created the world and he cares and protects and speaks to his chosen children, the Israelites. That's just how it is. As I said, this certainty has a definite appeal.

In my mind I sometimes separate people who can decode an effect, and those who are manipulated by it. Perhaps an arbitrary distinction, but a useful one to employ here. Growing up with a number of people who believed in the Bible wholeheartedly and quite literally, I know that these people look at the Bible and think that's how things used to be. In fact, their faith almost necessitates such a viewpoint. So, they long for a return to that certainty, when God led the Israelites by hovering directly over them as a pillar of fire. Then, they blame and rail against heathens like you and me (me, at least) who have undermined that certainty, who have chased God off the world's stage. And they're right – but not the way they think.

(I am very interested in hearing about this “cult” though.)

LikeLike

The story of The Golden Calf provides a fine example. When I was a wide-eyed kid, fully submersed in Christianity, as in a warm bath, it struck me as foolish that the Israelites would abandon God so easily and begin praying to the Calf. But that's viewing it all through the lens of Biblical certainty. If you look at, as we look at the world today…well, that sort of thing happens all the time.

LikeLike

When I was younger I got in an argument (meant to be friendly discourse, turned into something else) with the pastor of a youth group trying to convince me that coming to church (and his bible study class) was what I needed in my life.

I said “I've read the bible. It's hard to read and understand. Why don't they rewrite it so it's easier to comprehend?” He replied “These are the words of God Himself (speaking in capital letters and literally thumping the bible in my face) and we are mere mortals. Who are we to change the words of God?”

I countered with “The bible is translated from fourth century manuscripts at best. The closest thing we have is written three hundred years after the so-called events. And I seriously doubt that the people back then said Thee and Thou and Shalt and Unto. I'm sure most of them spoke in conversational tones, just like everyone else. Not fourth century colloquialisms. Those translators changed the words into what they thought sounded heavy and godly. Why don't we just change them back?”

That conversation didn't go very well. After a very short time I was no longer really welcome there anymore because I kept pissing him off.

It's that kind of rigidity that has turned me off of most religions over the years.

LikeLike

You had a lucky escape, Rev. Or rather it was your inner health and natural immunity that protected you from a metaphorical virus that finds its victims amongst the unhappy, for it grants them a rigid 'happiness' that denies the very void from which it arose.

LikeLike

Bryan, bless you for the Golden Calf! You have provided me with the perfect metaphor which I might borrow for use in describing “The Cult”. To be honest, I see it now as the Heart of Darkness (“the horror! the horror!”) and it would be impossible to speak of it in ordinary language. For me, it's a no-go area of mindf—. Squirming unhappiness disguised as its opposite. An AIDS-like virus that attacks the psyche—and physically crippled me too. Some kind of heroin or crack that all but destroys you.

I was lucky to escape, but the bonds, my friend, were inward. The language and rituals became invisible over the years, so that there was nothing to see. It became a secret language amongst the initiated, where the blandest thing had its own sinister meaning.

I'll have to find a form of language to describe all this, without succumbing to its horror. A roundabout, almost a science-fiction way.

But my heart says “Don't even go there.” It's a Chernobyl of the soul, Bryan. (And I'm writing this comment also for another reader, who will know what I mean, yet deny everything I am hinting at.)

LikeLike

Describing the eldritch horrors lurking there….

Did you perhaps study at Miskatonic University?

LikeLike

Daniel Dennett wrote a fascinating article in the Christmas edition of the New Statesman magazine on how certain kinds of social phenomena (including religious ideas and practices) can be better understood by analogy with the behaviour of bacteria.

Unfortunately, the NS does not have that article on their website, but there is a reasonable synopsis and consideration of it which gives the flavour that you can read in this blog

It seems relevant to the matters under discussion here.

LikeLike

I never even heard of Miskatonic University till now, Rev. But I'm grateful for the tip, and will try to make sure that my grandchildren don't apply to go there.

And your mention of eldritch horrors is just in time. That's not the tone I mean to evoke. Will moderate language accordingly.

LikeLike

Gentleeye, that link came precisely at the right time! Bless you for it. I particularly latched on to that notion of the membrane.

I think when I write about The Cult, it will be in terms of its universality: a form of social behaviour which pervades life in various ways, & which can get a strong hold on a person when the conditions are favourable—like a bacterium!

LikeLike

I was all set to object to that bacteria analogy as deliberately inflammatory, but then I read the article and found it very apropos of our discussion.

On a side note: I wonder if the use of fossil fuels would also qualify as a “parasitic tumor” on society, one far more malignant than the Japanese tea ceremony. Certainly there's no good reason, technologically, why we can't have cleaner-running, fully electric, cars at this point. If we were still lighting our homes with oil lamps in this computer age, we would consider it absurd, and yet that's basically where we're at with our vehicles. It seems like the use of fossil fuels persists because, like the tea ceremony or religion or any number of things, it is so entrenched economically, politically, socially, and even structurally.

LikeLike

My instant reaction to your comment on the fossil fuels being a parasitic tumour on society is to agree, but take it further and include the car itself.

The significant difference between the petrol or diesel car and the electric one is presumably pollution.

But the damage caused by cars, in my opinion, is hugely greater. They have destroyed the sense of local community as a self-regulating bastion against family disintegration, unsociable behaviour, neglect of the vulnerable, some kinds of crime, etc.

They are isolation cells separating us from nature and one another.

I know the USA is a big place, but it managed OK with its railway system up to a certain time, and since then it seems you need a car the moment you are old enough to get a driving licence. I presume that not having access to a car, e.g. through poverty, confines you to something like a ghetto?

I imagine that not having unlimited availability of fuel is the spectre of hell to Americans generally, and one of the main justifications for foreign intervention & alliances.

Were I looking for a thesis to write I might try to link American hunger for fuel to the 9/11 bombing. I hope this is not considered intrinsically offensive. Wikipedia says “… the al-Qaeda leader was motivated by a belief that U.S. foreign policy has oppressed, killed, or otherwise harmed Muslims in the Middle East …” I follow its link to US Foreign Policy and search on “oil”. I find “President George W. Bush identified dependence on imported oil as an urgent 'national security concern'.”

Gosh. Wikipedia makes it so easy to write a worthless thesis (a phrase which I find myself unable to say aloud).

But I do think that such dependence on the motor-car, as we quaintly call it, as opposed to the automobile, does destabilize the world.

I imagine a counterfactual history where the Pilgrim Fathers and other white immigrants “went native”, and adopted the ways of the “Indians” they found already there.

I'm so attached to the footpaths and bus-routes we have here. If some strange bacterium caused parasitical tumours in all the private cars in England, it would be a recoverable catastrophe not much worse than the earthquakes in New Zealand or Japan.

(My step-brother lives in the epicentre Christchurch and his wife is Japanese.)

LikeLike

If fossil fuel dependence could be considered a parasitic tumor, then our cell phone addiction must be considered malignant from the way it grew and spread so quickly.

LikeLike

Why is it malignant, though? What are its malign effects? Is it destructive?

In Africa for example cellphones are considered very beneficial in communities otherwise isolated.

LikeLike

Eh, I don't know if I would go quite that far.

Don't get me wrong. Cars can be a major pain in the ass. The upkeep of one can be a constant headache. Plus, the fact that driving is such a necessity here in the U.S. basically means that they have to make the driving test so easy that any idiot with a face can get a license. As a result, you have millions of people on the road who have no business behind the wheel. It's hardly an ideal situation. And I agree with many of the other points you made.

However, I don't think that retrogressing to a horse & buggy, railroad transportation system is remotely realistic, or even particularly a good idea. The argument that people “got along” that way in the past is like saying, “People got along living in caves and everyone in the village wiped their excrement on the same dirty mammoth hide, so we don't need all these houses and cities and toilet paper.” I've noticed a tendency on your part to romanticize the past, a crediting of our forebearers with a certain unearned nobility, as though they are to be commended for depriving themselves of the creature comforts and technology that we regularly indulge in. I'm sure you realize how silly that is. People restricted their travel back then to railroads and horses because they didn't have a choice, because the car hadn't been invented yet. They are no more noble for that than we are for not using teleporters and warp drives. I'm sure even the 19th century had it's “Vincents” decrying the iron horse and its noxious smoke stacks as an abberation in the name of “progress.”

Not that I wouldn't entertain alternatives…or some sort of public transportation system, but it would have to be a workable, feasible solution. I mean, I like a good walk as much as you do, but as a practical means of getting around…I'm not sure you fully appreciate what a sprawled out country we have over here. Perhaps it could be done, but it would take a radical redesign of our entire society, and I don't see that happening any time soon.

I sympathize with your affection for walks and your romantic view of the past. I romanticize about the past myself, but I realize that I'm doing that. The past is a swell place to visit in my dreams, but if I went to live there I'd probably get tuberculosis and end up buried alive.

LikeLike

Plus, any proposed solution that involves some kind of mandatory retrogression always faces the same problem. Implementing it would basically mean outlawing people from using their minds to come up with any kind of new ideas or new inventions.

I wouldn't want to live in a world like that, and I'm sure a lot of other people wouldn't either. The Amish may look like they have a pleasant, idyllic society, but God help any little Thomas Edison's who have the misfortune of growing up in their community. They probably take them out back behind the barn and beat the impulse out of them with a stick.

LikeLike

We are not opposed on this, though we may have a different idea of an ideal world. We cannot go back to the past. The future may be threatened, in the sense that we cannot go on with the same kind of progress or even the status quo.

I'm actually feeling sad that it might hit America hardest, as well as frightened what America may do to keep its way of life. But most of all is sympathy for our descendants. It may be misplaced sympathy. They will adapt a lot better than I.

LikeLike

I understand. Such feelings are not uncommon, but they exist along a continuum, rather than a statement about this particular moment in time. The future looks bleak, the past bright and sepia-toned. Of course, the opposite argument could just as well be made, the past is bleak, and the future is hopeful and full of possibility. Since the future is what we have to deal with, I think the 2nd is the more productive of the two. The future is what we make of it.

Not that there aren't problems. American culture seems like it's on some deliberate collision course designed to destroy the soul, character, and integrity of the people. The “progress” with fossil fuels is no kind of progress at all, but rather a stagnation.

See, I read the article as talking about things which hold back progress and evolution, riders which have outlived their usefulness and overstayed their welcome, but which have dug in and cultivated their own survival in one form or another. The tea ceremony is an innocuous example, a tradition which persists for its own sake and which even has a kind of cottage industry build around it. The use of fossil fuels is a far more serious problem. It's clear to see that we should and could be beyond them now, but unfortunately it's also clear to see why we're not.

The automobile itself, on the other hand, could very conceivable find itself in the very same boat in the near future. Something could come along which should rightfully replace the automobile, but the entrenchment of society and the industry itself will resist it. In fact, it's practically inevitable that this will happen. In the meantime, the objection that some piece of technology or other, whether cars or smart phones or computers, should never have happened or that they're “destroying the world” – while debatable case by case – is not, I believe, the point that the article was driving at. In fact, I believe they were trying to serve up an inoculation to this very sort of suspicious resistance to change.

LikeLike

To be honest, I read the article only in the context of my next piece “The Cult”. But on the topic of transportation, the thing I like about the internet is its role in obviating the need to go anywhere physically.

Last night I watched the 1986 remake of The Fly in which Jeff Goldblum's character Brundle invents teleportation. It is infinitely better than the 1958 version, thus illustrating to my sceptical eye that there is such a thing as progress!

Brundle suffers easily from car-sickness. He looks forward eagerly to the day when his invention will transform the world. As horror films go, this one can hardly be bettered.

I had thought the 1958 version couldn't be bettered but it was tame when I actually got to see it.

It was in the school playground in 1958 itself when a fellow-pupil told me the plot. I didn't manage to see the film myself, except in my mind's eye: a depiction which stayed vivid in my imaginary cinema for fifty years. Now made obsolete!

LikeLike

Oh yes, The Fly is a definite classic (the '86 version. I never saw the original.) It works well as a horror movie. Turning into the monster is even worse than be stalked by one.

Also, our discussion of progress and transportation reminded me of these lines last night:

Well, he cursed all the roads and the oil men,

and he cursed the automobile.

He said, “There's just no place for an hombre like I am

in this new world of asphalt and steel.”

Then he'd look off some place in the distance

at something only he could see,

and he'd say, “All that's left now of the old days

are these damned old coyotes and me.”

LikeLike

In other news: After seeing every post footer floated with links to The Pagan Sphinx for as long as I can remember, I finally gave in, checked it out, and now I'm following.

LikeLike

Excellent! Gina has pointed out that these links are not a result of shameless self-publicity on her part. They seem to occur spontaneously.

LikeLike

Books as sacred places is a truly fundamental idea. And you put in well.

In his “Politics and the Engish Language,” George Orwell famously parodied a passage from the King James translation of Ecclesiastes…

“Now that I have made this catalogue of swindles and perversions, let me give another example of the kind of writing that they lead to. This time it must of its nature be an imaginary one. I am going to translate a passage of good English into modern English of the worst sort. Here is a well-known verse from Ecclesiastes:

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

“Here it is in modern English:

'Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.'

“This is a parody, but not a very gross one. ….”

Orwell had a point when he argued that biblical language is largely better than modern [political] language.

It's just that the bible is chock full of nonsense also.

LikeLike

“All that's left now of the old days

are these damned old coyotes and me.”

Thanks for the introduction to Don Edwards and his song, “Coyotes”. Wonderful. And a perfect illustration of the role in the world of the old man: to remember, to remind. To tell the young folks that things happened before they were born. They may have been washed away in the stream of time, but they were worthy, and they are irreplaceable. Just as there is a consciousness today of keeping species from going extinct, there are other things too. They might not be species. They might be ways of life, old languages, forms of behaviour, sounds, sights, scents, and so on. But their passing is to be regretted. When someone dies, he is mourned by those who knew him and valued him, even if he was bad and the world is a better place without him. How much more should we mourn those things which exist within living memory, but are no more?

I come from a generation whose parents, grandparents and teachers valued the past more than the present generation's parents, grandparents and teachers. So I feel connected to people and events going back to Queen Victoria and Alfred Lord Tennyson, for example. I feel connected to Tennyson through a myrtle bush I'm carefully nurturing in the backyard, cultivated from a cutting of a cutting of a myrtle garland worn by his bride, on 13th June, 1850. Which is nearly 162 years ago.

But the thing which connects all of us to the past, as a constant wonder to behold, is us and the rest of Nature. We are all, in a sense, living fossils, in that we go back a very long way, demonstrating by our very existence that we have survived extinction. This is not quite the accepted meaning of “living fossil” but does convey a sense of how to live today in consciousness of the weight of the past.

And this may explain why, the older we get, the more conservative is our outlook: the past weighing more heavily than the future!

LikeLike

Amen to that, Brett! I had a quick peek at your blog, which I have never visited before. And as for your post on slow cities, olé to that too! To me, this little town (I call it Wye Vale) in Buckinghamshire is a slow town, regardless of being so much uglier than Barcelona; and regardless of the young immigrants racing unsociably down the local streets in cars so expensive that I cannot but think “drug dealer?”

LikeLike

That song is one of my favorites. It's like a mythical elegy.

And it's true what you say about the past. There IS a feeling of loss when the world moves on, and even more so, I'm sure, when it eventually comes to feel that the world has moved on without you. I'm turning 36 next week and there are already plenty of things that I yearn for in my memory, just out of the fact that they are lost to time. There are all those little things that happen right in front of me, a building gets torn down, a new something-or-other gets implemented and I groan inside and think, “Did they have to change that too?” It's disheartening.

When I was looking for my house, I deliberately made it a point to find an older house. In fact, this place, built in 1927, is fairly new compared to what I had in mind. I love the old Victorian homes around here, but finding one in good shape for sale isn't easy. The race in home building, at least here in suburban American, in the last 50 years or so has definitely been to the plain and ugly (to borrow from Ecclesiastes ;D ) And of course, I've talked before about my affinity for the typewriter and the printed book.

So I more than sympathize. It's that inevitable dilemma, torn between a curiosity and an eagerness for what the future holds, and a…well, as my own past self said:

Sometimes we wish that we could crawl back into these memories and somehow live inside them all over again, not to change things, but just to be there again, to feel the way the air felt different then, to look into the eyes of someone who has long since slipped away, to really savor and appreciate those moments in a way that was impossible the first time around when we had no idea how fragile and transient they were. But the wave of time pushes us farther and father away from these memories. We struggle against the sweep of the wave, straining to reach back and grab a hold of these things. But the wave says, “No. We have to keep going.”

And I'm sure, as you say, that the scale tips more in that direction as we get older. And I most certainly appreciate those who have endured, who have persisted, who have seen it all pass before their eyes, and who tie us to that past. They ALWAYS have the best stories to tell.

LikeLike

A long time ago people assumed that the ancient history in the Bible was true simply because they didn't have anything else to compare it to but as time went on they gradually got used to the idea that it wasn't literally true, and it didn't have to be. Science can and should teach us about the way the world works but why the world and the universe is is best left to poets and philosophers, and yes as well, to literature in general.

LikeLike

Bryan, I’m definitely at the point where the world has moved on without me. It didn’t ask my permission to make all these changes, just did them sneakily behind my back!

LikeLike

Yes, Susan, amen to that. The role of religion has inevitably changed, now that there are more believable explanations for things. There are those with long memories who don't like the changed role. Religions by their nature are conservative.

But literature is a good resting place. The old books themselves don't change, and can be appreciated without belief or interpretation.

LikeLike

Gentleeye, I did manage to get hold of the original article by Daniel Dennett, through my library, which offers access to Infotrac and an electronic online version of the New Statesman.

So your tip has opened a door to important discoveries. Thank you!

LikeLike

I am delighted to hear it, Vincent. Another reason to defend our libraries – the home of many sacred spaces (and portals)!

LikeLike

A few years ago, (already at a respectable age…whatever that is!), when I started to read blogs and seriously commented on a few, I was encouraged to start a blog. When I told a (very interesting, very well read) gentleman that I would put on my profile that my favourite book is the Bible, he replied, “Then I would not follow your blog.”

I was so amazed. Still am….

I could have said so much about people who are afraid of a book that they don't believe in. And who are afraid of people who read and admire the language of this book. But I said nothing…

Today I'm glad. You said it so much better than anything I would have written.

Thank you.

LikeLike

It's good to find you here, Claude! And of course I agree with what you are saying.

You've inspired me to persist with my ongoing task to produce an e-book omnibus of this blog, to be called “A Wayfarer's Companion”, in which the themes are indexed, the better posts given more prominence, and selected comments are included.

LikeLike

It's very good, presently, to have access to “A Wayfarer's Notes”. But it would be fascinating to read “A Wayfarer's Companion”, re-arranged as you describe it.

As I'm already at a respectable age, I hope you will hurry the process. I would so much enjoy sharing my reactions to the book.

All the best to you, and yours, for the Holiday Season.

LikeLike

And to you too and yours too, Claude. I'll email you about the omnibus edition.

LikeLike

“Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?”

Epicurus.

LikeLike

Brett! We haven't spoken for a long time. Such questions as those of Epicurus are still being asked, of course, and my latest series of posts has had a subsidiary aim of obliquely addressing them.

Essentially, let those who use the word God sort it out for themselves. It's a dead end to assign attributes to God and defend them in the witness box. God is essentially unknown except for numinous subjective experience & the rest is mythos as Karen Armstrong calls it in her book The Case for God.

LikeLike