Lately I seem to be getting more from literature than from life. A misleading observation, since reading is an act performed like any other, in life, as opposed to a dream. Again, this is misleading. Leisure reading fires the imagination as dreams do.

Lately I seem to be getting more from literature than from life. A misleading observation, since reading is an act performed like any other, in life, as opposed to a dream. Again, this is misleading. Leisure reading fires the imagination as dreams do.

By “life” we sometimes mean living, in the sense of an interactive drama with consequences, like a bullring where Self is the strutting toreador duelling with the sharp horns of the Other; showing who’s boss, or if that fails, reaffirming the right to hold one’s head high, one’s fitness to occupy space on earth. Or the feminine equivalent.

Literature by contrast is that unearthly space, that Neverland, that ivory castle of possibility where only one rule is inviolable—to maintain, as Coleridge puts it “that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith”. But reading, real active reading, offers the acute thrill of discovery, strong as any adventure you care to name.

Perhaps I can rescue reading from the charge of escapism, and compare it with sky-diving, say, or surfing the glassy waves in Tahiti. I think they have a lot in common. One tends to belittle reading just because it’s so much more accessible. We are beset on all sides with reading matter, top ten bestsellers, everything preselected on our behalf. But go further to the less-trodden wilderness. There we may find adventure, including skill, danger, glamour, investment, exposure, physicality. Let’s examine these things.

I’ll grant you that reading lacks physicality. That’s the thing I most dislike about it, actually, or possibly the thing I most dislike in myself when I’m reading. I like to lie on my bed, propped on pillows, comfortable to the point of dozing off. Or, still attentive, I grudge the effort to hold up my heavy book or awkward Kindle reader. (The page-turning buttons are positioned exactly where you would like to hold the thing whilst lying on your back.) Better, I think, to have the words projected on the ceiling. But then I would have to keep my eyes open: even that is too much effort for perfect comfort. There are audio books which exist to cater for such lazy inertia, but I don’t like them. Paradoxically, they also cater for the fitness freak. In principle, you could sky-dive with your earphones plugged in tight, listening to an actor reading Silas Marner. It would be an abomination, of course. The one adventure would numb and nullify the other. Those joggers and cyclists who entertain themselves with audio books clearly find their self-propulsion through space an insufficient adventure. I’m sorry for them.

Is reading dangerous? According to my mother, reading in dim light would “hurt your eyes”, but mine still work fine sixty years later. Censors, religious or secular, have always taken the view that reading the wrong thing is risky like visiting a brothel: you might pick up some spiritual disease. There was a time when reading Karl Marx might shorten your life, if it inspired you to take up arms as a revolutionary. It used to be thought that for children at least, certain “literature”, in its broadest sense, was dangerous. Nowadays parents are more concerned with the dangers of their children not reading. “Parental guidance” is reserved for images, moving or still. To sum up, we compare estimates and conclude that the dangers of reading compared with sky-diving are marginal, or controversial. I conduct an imaginary poll and discover that most people think reading is less of a sport than chess, though more dangerous to the persons involved. Only Jehovah’s Witnesses warn about the dangers of chess. (Source: Awake magazine, 1973.)

One thing that’s noncontroversial is exposure. Almost by definition, an extreme sport is one in which spectators are watching for the chance that you might fail—get injured or die. There are dangerous sports where no one can watch. Caving is a good example: it’s dangerous precisely because you’re on your own. Reading is obviously different. If you don’t want people to see what you’re reading on the bus or Tube, you can conceal its cover. Only the book reviewer experiences the thrill and danger of exposure. He’s a special kind of reader who exposes himself for money. He duels with the author. I often feel the urge to publish a review of the book I’m reading, but it tends to be homage, rather than a critical guide; and the urge invariably fades before I’m halfway through. In the matter of exposure, reading is not in the league with motor-racing or sky-diving. There’s seldom blood or broken bones.

I mentioned skill, investment and glamour, as components of adventure. If you embark on Proust, Finnegan’s Wake or Homer, you may discover it’s like running a Marathon, testing your fitness and stamina. I don’t read to prove myself, not any more; but to harvest a gift still fresh and ripe even though the author who left it for me may be long gone.

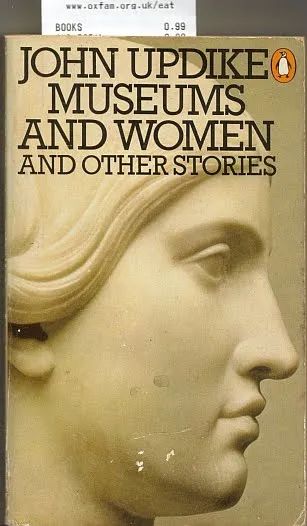

This essay was inspired by John Updike’s short story, “Museums and Women”, first published in The New Yorker, 1967. It’s a set of linked anecdotes, each of which involves a museum visit and a woman, the first of whom is his mother. He’s fascinated by a collection of small bronze nudes:

They were in their smallness like secret thoughts of mine projected into dimension and permanence, and they returned to me as a response that carried strangely into parts of my body. I felt myself a furtive animal stirring in the shadow of my mother.

My mother: like the museum, she filled her category. I knew no other, and accepted her as the index, inclusive and definitive, of women. Now I see that she too was provincial, containing much that was beautiful, but somewhat jumbled, and distorted by great gaps.

Updike’s story helped me find an illustration for this post: a woman in a museum. He writes:

I one day discovered a smooth statuette of a nude asleep on a mattress.

I searched Google Images to see if I could find such a one. What I found was the disturbingly seductive combination of a marble Hermaphrodite, of Roman origin, and a more recent mattress, sculpted by Bernini in 1620.

One of his anecdotes is of “the girl who was to become my wife”. He struck up a conversation with her on the museum steps in the snow, where she stood smoking in ragged sneakers. I quote:

“… It would never occur to me, for example, to stand outside in the snow in bare feet.”

“They’re not really bare.”

Nevertheless I yearned to touch them, to comfort them. There was in this girl, this pale creature of the college museum, a withdrawing that drew me forward. I felt in her an innocent sad blankness where I must stamp my name. I pursued her through the museum….

Oh, that innocent sad blankness! How many girls have tantalized me with that space, where I just wanted to stamp my name! And thus, in my reading, I find that sharp poignant joy of discovery, rolling back all the years to the love affairs I had, and especially the ones I merely imagined. Updike’s narrator proposes an equivalence, of museums and women:

Both words hum. Both suggest radiance, antiquity, mystery, and duty.

Yes, but it’s not the museums I miss.

I love this post! There is a subtle and yet delirious absurdity at times, probably my favorite kind of humor, the sky-diver listening to audiobooks, your imaginary poll, ect.

I also love reading, and you do a fine job of capturing exactly why, the places it cultivates in the imagination, the relief from the perpetual challenges of dealing with other people. I don't begrudge reading's lack of physicality though. I get about as much “physicality” as I can handle from my job, and I welcome the mental diversion as a refreshing change. Although, the Kindle projected on the ceiling…now that's lazy, and yet…an undeniably great idea 😉

LikeLike

Glad you liked it, Bryan. You got in so quick I was still editing it at the time.

LikeLike

I do think that reading can be an extreme sport if you let it be. Not so much a physical sport but a mental and emotional one. Much like if you played chess where one piece had to actually defeat another one in some manner of combat in order to make a successful move. Some books are more sedentary emotional entertainment where you drift along in a happy daze and lay it down at the end with a smile. Others you have to wrestle with and take you on a mental roller coaster. When you finally close it again you feel like you have gone ten rounds with Jack Dempsey. Battered, bruised and maybe even bleeding, but smiling at the final bell. In victory or in defeat, you are happy that you survived the battle and managed to walk away from it in the end.

And on a side note, I have always been a fan of Bernini. he put so much eroticism in his work that it startles me even to this day that he did most of his work for the church.

LikeLike

The essay emotionally swung back and forth into many scenarios. You must have used up some calories not only in the reading that generated it, but in the sensations that formed the creation of the post. Not to mention the exercising of the digits in typing up the construction of your words.

Nice one! Or, in Facebook response style'thumbs Up'.

LikeLike

Ah, Vincent, I openly admit to being an unrepentant reading addict. The idea of not having something to read, not having a book “on the go” is inconceivable to me.

When I am travelling, I always take too many books with me for the period planned; the idea of ending up somewhere with nothing to read is just too ghastly!

One of the wonderful things about books is that they all contain worlds within their covers – worlds which can be revisited.

A beautiful post … from one reading junkie to another.

LikeLike

Then, Francis, you need a Kindle reader! You can fill it with hundreds of books' worth of reading matter.

As for those worlds which can be revisited, I think it applies only to a memorable minority of books. To forget the unmemorable majority comes naturally, of course.

LikeLike

I suppose I do use up a few calories when reading, ZACL, but would guess that measured in nano-calories per word, writing uses up more than reading by a ratio of at least 1000 to 1. I think it would be impossible to measure actually, for writing isn't just the scribbling and typing but all the unconscious brooding as well, including whilst asleep—I reckon.

LikeLike

Rev I agree with your every word except one: “always” – for I have not always been a fan of Bernini. But I certainly am one now. See, for example, this detail from The Rape of Persephone. It looks shockingly modern, too.

LikeLike

I saved that picture and I am going to have to look at it again and again, I believe. I've always been fascinated with the great sculptors and to be able to do something like that with stone and make it come out looking like living giving flesh is nothing short of certified genius. My mind just reels. Thank you for bringing that lovely tidbit to my attention!

LikeLike

I am a keen bibliophile myself. My Library currently consumes much of the space in my tiny house.

A friend recently suggested a acquire a kindle(a device for storing and reading thousands of books electronically). After much thought I realised why this idea presented some distaste. For me reading is more than just a means of intellectual stimulation its a tacticle experience. I love the feel and even the smell of an old book. I'm sure this has some profound psychological meaning however I am never more comfortable than when reading a well written book whilst my senses are being similarly soothed.

LikeLike

Yes, Asclepius, the resistance to Kindle (flip side of loyalty to books) is almost universal. I've felt it too, but a new loyalty to the Kindle kindled in me quickly, because this Mk3 version (out nearly a year now) is so good, and meets so many hitherto undreamed-of needs, that books and bookshops can't meet.

I buy on price, getting a second-hardback when I can, for the reasons you mention, if it is the cheaper option. Most of what I read on Kindle is self-downloaded rather than from the Kindle shop. Stuff I write myself, things off the Net, out-of-copyright things from Gutenberg (most of which are available in Kindle editions, otherwise easily converted).

For the booklover in you I would offer this: that since getting the Kindle in February, I've bought more real books than ever before. Because more reading leads to more curiosity and more connections!

LikeLike

Rev, I believe you! Let us start a sculpture appreciation society. Do you know I helped make a film about Michelangelo in Florence? For Coronet Films of Chicago (now defunct)?

Still, Michelangelo doesn't have the sensuous appeal of Bernini, who knows how to make breasts look like breasts, and not pomegranates.

LikeLike

I'd love to track down a copy of that film somewhere. I definitely prefer Bernini's female sculptures to Michelangelo's. It seems like all of his women were badly disguised men. It makes me wonder. If Michelangelo was obviously so preferential to men, why did he make them so poorly equipped? Were I so inclined to make my own statue of David to serve as a model of the perfect male form Victoria would have had to use a palm frond rather than a fig leaf.

LikeLike

I wanted to track down a copy of it too, and you'll see from the comments thread on that post that the son of the cinematographer made contact. i was hoping to discover if Leo Rogelberg remembered me after all these years, but the trail has gone cold.

As for the matter of sculpted male dimensions, you might take the trouble to check up on a 20th century sculptor, Eric Gill, who used to live not far from here, though long before my time. It was he who created the type face Gill Sans. He also sculpted the statue of Ariel which adorns the BBC's Broadcasting House, built 1932. The BBC's founder, Lord Reith, thought that the boy Ariel looked too well-developed, so Gill lopped it a bit, so to speak.

As for the Michelangelo film, it can be bought on DVD from Phoenix Learning Group for $25 and you can watch a sample (filmed in Rome – I wasn't involved). I wrote to them but never got a reply. I would like to get a copy though!

LikeLike

The film is also available in various educational libraries in the US.

LikeLike

Whew! That led me on a merry chase. Loved Gill's work. And I'm kind of glad I never knew him. Personally, anyway. What is it about those with creative genius that makes them all completely barking mad?

LikeLike

I just updated the post a little. And Rev, if you are still there, I did buy a copy of the DVD of the movie I helped make, through Amazon. It's only 16 minutes long, and (presumably in the manner of all Coronet films) is devoid of credits. But there are bits I remember.

LikeLike