I’ve never taken this trail before, this walk to Marlow on the first day of February, on a cloudless frosty day. How often it happens, on my wayfaring, that something triggers a memory, perhaps of a single second in my life, usually in childhood, for it was then that I most frequently encountered something for the first time, and entered openheartedly into—that experience. That second expanded then and expands now, almost to infinity. Perhaps it was a colour, something sparkling, something translucent, something which glowed; the slightly blue-tinged green of a field, with its shoots of young wheat. Or a newly-ploughed field, where the plough had brought to the surface a large white flint, and I stared at it. You see, there’s a feeling, but I can’t say what it is.

I’ve never taken this trail before, this walk to Marlow on the first day of February, on a cloudless frosty day. How often it happens, on my wayfaring, that something triggers a memory, perhaps of a single second in my life, usually in childhood, for it was then that I most frequently encountered something for the first time, and entered openheartedly into—that experience. That second expanded then and expands now, almost to infinity. Perhaps it was a colour, something sparkling, something translucent, something which glowed; the slightly blue-tinged green of a field, with its shoots of young wheat. Or a newly-ploughed field, where the plough had brought to the surface a large white flint, and I stared at it. You see, there’s a feeling, but I can’t say what it is.

And then I try to communicate in words, and find that more words won’t make it easier. Fewer words are better, when the task is to point towards something that can only be felt. It is not my description that will make things clearer to the reader. It can only be the reader’s own journey, which I must not hinder—to an untouched place, an archipelago of imagination.

I’m fully aware, John Myste, that I have not responded to your generous comment on the topic of poetry, appended to my last. I shall be lazy and not respond point by point, but merely dedicate this whole post to you, hoping you will forgive. Like you I am utterly beguiled by the magic and possibilities of poetry. Like you I am unimpressed by most poetry. It had an impact in my teens and I still like the same things now as then; my favourite of all time being one by Laurence Ferlinghetti: “Away above a harborful …”. Poetry takes us to places we don’t know but its magic is to make them reachable and even shareable.

And this is how I would define my god, if I wanted to use the word, which I most certainly don’t: a Presence, an attentive Presence, there in times of need; the need to give thanks and the need to beg, and the need to surrender one’s life to something higher. To surrender in advance if you will, because death will come willy-nilly, death the force majeure. It forces us to let go of all that we know with our mortal mind. But perhaps there is an immortal mind, always hidden, or perhaps not so hidden. Perhaps the immortal mind takes wing after death, why not? Yet one can dwell contentedly not knowing.

At this point I have just been overtaken by a fellow wayfarer, on this beautiful footpath. She’s walking faster. She said something as she approached from behind, so that I wouldn’t jump in surprise. What a gracious person! One of those angel-sent strangers who greets and passes on, the human manifestation of an invisible Presence, leaving me to resume this conversation with the world.

It’s a spot on the map called Burroughs Grove Hill. There’s nothing much here, apart from the landscape. I take a bridle path which wends its way, over hill and down dale, till it reaches Marlow Bottom. It’s undoubtedly ancient, probably prehistoric, but in this moment I feel it as mediaeval. I wouldn’t be surprised to encounter a travelling vendor carrying silks, ribbons and lace, to show to the high ladies in the castle; a juggler on his way to the Fair; a mountebank, or a jester in cap and bells, clad in motley. Or, I could see in my mind’s eye a boy here, driving his pig to market with a stick.

It’s a spot on the map called Burroughs Grove Hill. There’s nothing much here, apart from the landscape. I take a bridle path which wends its way, over hill and down dale, till it reaches Marlow Bottom. It’s undoubtedly ancient, probably prehistoric, but in this moment I feel it as mediaeval. I wouldn’t be surprised to encounter a travelling vendor carrying silks, ribbons and lace, to show to the high ladies in the castle; a juggler on his way to the Fair; a mountebank, or a jester in cap and bells, clad in motley. Or, I could see in my mind’s eye a boy here, driving his pig to market with a stick.

The well-known Ridgeway, a few miles west of here, is reputed to be the oldest road in Britain, dating back to prehistory, but give me this one, which has no name! It has been spared the indignity of motor vehicles. They run on parallel roads, ones which go round the hills, not up and down them. It’s too steep here for any but foot-traffic.

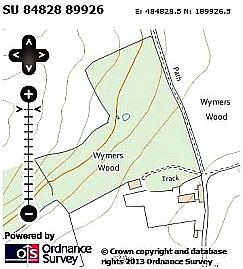

Birds are singing joyfully in the hedgerows, as if to herald Spring. I don’t know which path to take. I am near to a copse closely planted with young ash trees, I recognise them from the smooth grey bark and the black buds. There are paths through it, and paths beside it.

A website tells me (I check later):

“There is a buffering strip, Kimber’s Copse (Compartment 3), to the eastern side of the wood to protect this ancient wood from further damage by agriculture practices or development pressure. This is naturally regenerating well with mostly ash and some oak seedlings.

The site has an extensive network of well-used public paths that are clearly appreciated by the local people who walk them. There is strong support from the Marlow Residents’ Association for the management regime in the wood.

Once again, my memory goes back to my time as a five-year-old, in Holland, in 1947, though I was never there in this season. Almost all my memories of that time are of wandering alone in the open air, absorbing new experiences. Certainly I went the mile or so to school on my own, and I don’t think I always took the most direct route. It was near Arnhem, not long after the war ended. I didn’t see wreckage of planes, they would have been quickly recycled I supposed, but there were little items scattered in a field: nuts and bolts, tiny fragments of mirror, glinting in the sun.

I was only five, but I can visit it again, with my adult brain looking through the child’s eyes, a kind of Remote Viewing, but in time, not space. This life is glorious. There was a metal plaque against a tree, I tried to photograph it on my mobile phone. It wasn’t too legible but this was the gist:

“Part of the surrounding nature reserve is dedicated in loving memory of Olga McDonald who loved nature and reading and hated ginger biscuits … & inspired our interest in all living things … educated us not just to look, but to have a…”

Later, coming near to a few houses, there’s a tree hung with catkins, sure sign of wintry regeneration. It’s also hung with several green net bags of peanuts, already pecked clean by the birds.

And I feel that whoever took the trouble to put up that plaque, remembering a grandmother, I guess, and whoever hung bird food on trees out in the countryside at some distance from their own house and garden, did so feeling a Presence.

Now I come to human habitations. The footpaths are sacrosanct. They go straight through between the houses, narrower now between the high fences of adjacent back-gardens. Over these walls I hear men’s voices, like the droning of bees, women’s like the chatter of birds in a tree. The sunshine is bringing out householders and their neighbours on any excuse to rejoice and look for premature signs of Spring.

I hear children’s voices in the distance, echoing in the woods. I descend a steep urban footpath with a handrail in the middle, to which someone has strapped a child’s wristwatch. I gaze closely at its dial. It’s working, telling perfect time, waiting for its carefree owner to come back looking for it. Who says time and tide wait for no man? I have just seen the disproof. This place has somewhat of the free-and-easiness of the place I was born in the Forties, in Bassendean, a suburb of Perth, Australia, in which I spent my first four years.

I may be wrong but I think that the moments which I go back to, the ones which expand almost into infinity, are those which weren’t used up the first time round. They happened but they weren’t fully lived and savoured. How fortunate to be able to live them again.

By the time I get to Marlow, I’ve walked eight miles. I take the bus back.

This is great. I know what you mean about poetry. Like many writers I went through a “poetry period” when I was young. A filled plenty of notebooks, most of it with garbage. Somewhere along the way I moved on to other things and other forms. I also like the idea of poetry, but when I actually encounter a poem my first reaction is usually…uggghhhh. I still love some poems, “The Raven”, “The Road Not Taken”, “Death Shall Have No Dominion”, but so much more of it seems like a chore to read. Perhaps, ironically, I'm putting a more prosaic face on what you're saying. Also:

“…those which weren’t used up the first time round. They happened but they weren’t fully lived and savoured.”

I have nothing to say or add to this. It's perfect the way it is.

LikeLike

You never need respond to a comment unless you are moved to do as. I offer this as the non-gentlemen's perspective. I often do not respond to comments, as I feel they stand on their own and are complete.

“The moments which I go back to, the ones which expand almost into infinity, are those which weren’t used up the first time round.”

That line is the quotable in this piece.

LikeLike

Vincent your description

“And this is how I would define my god, if I wanted to use the word, which I most certainly don’t: a Presence, an attentive Presence, there in times of need; the need to give thanks and the need to beg, and the need to surrender one’s life to something higher. To surrender in advance if you will, because death will come willy-nilly, death the force majeure. It forces us to let go of all that we know with our mortal mind. But perhaps there is an immortal mind, always hidden, or perhaps not so hidden”

is one of the most beautiful definitions of God I have come across so far.

LikeLike

and, a beautiful description. You are very fortunate to have such wonderful countryside nearby for walks neither overbuilt nor completely desolate.

LikeLike

Thanks, Ashok. I retraced my steps over some of that walk yesterday, going with my wife, on a more blustery but warmer day. We both felt how fortunate we are to have those walks nearby. Yes our start and end point was from a supermarket next to a noisy motorway, down muddy paths strewn with litter and abandoned supermarket trolleys. It didn't look promising at all, but I knew it would transform completely within ten minutes into that beautiful countryside.

LikeLike

John I am moved to respond now. You are a gentleman sir.

LikeLike

[…] “And then I try to communicate in words, and find that more words won’t make it easier. Fewer words are better when the task is to point […]

LikeLike