Matt Lowe of the blog “Liberal Jesus” wrote a post pointing to an article in the New York Times. Matt admitted “I can’t figure out quite what I think about it. I need a little goading I think.”

I hastily appended my own working definition of happiness: that it’s when one can say “I don’t ask for more than this. No conceivable event could snatch this from me.”

Professor Sosa in his article proposes that happiness is not merely euphoria, the kind that could be induced by certain drugs, perhaps, or some joyful event, real or imagined. It has to be linked to something solid in the real world. He offers a thought experiment: would you plug in to a “happiness machine” that would feed you with certain realistic illusions by manipulating your brain function? This makes him digress into how we decide between options. In extremis we follow instinct; but when we are rational we imagine the outcome of each option and act accordingly. Which has nothing to do with happiness as I envisage it. “I will be happy if I win the Lottery” expresses a double hope, that achieving the one will also achieve the other. It has nothing to do with now.

But I stay with Prof Sosa for the time being, when he asks “Would you plug in to the Happiness Machine or not?” To him, the choice is between happiness seized from Reality, or happiness injected by a Dream Machine.

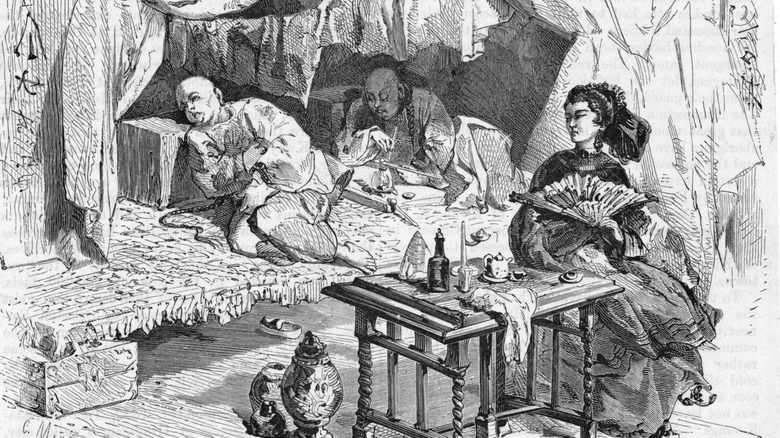

So then it occurred to me that we already have these machines. In the nineteenth century, an opium den was the paradigm, leading Karl Marx to make his famous observation about religion, reproduced below thanks to Wikipedia:

whose spiritual aroma is religion. Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people. The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.

I n the nineteenth century, an opium den was the paradigm of a happiness machine, leading Karl Marx to make his famous observation about religion:

n the nineteenth century, an opium den was the paradigm of a happiness machine, leading Karl Marx to make his famous observation about religion:

A clear-eyed modern critic of capitalism would see how thoroughly it outperforms religion. What does it do but produce opiates? It creates a hunger for unnecessary luxuries and fosters the craving for them. In Western civilisation we’re already plugged into a happiness machine! This rather nullifies Sosa’s thought experiment, for we have been brainwashed, if that’s not too strong a term, into seeing happiness as something sitting on the shelf with our name on it, not yet claimed. So happiness is a combination of security—I could have this now if I wasn’t prudently postponing it—and eager anticipation—thank God it’s Friday!

I think Sosa is hardly in a position to offer his thought experiment to his students and readers of the New York Times. Anyone who’s already plugged into such a machine, albeit a metaphoric one, is not unbiased enough to make an informed choice between reality or ersatz. This may not be obvious. As he says:

There’s an important difference between having a friend and having the experience of having a friend. … Now, of course, the difference would be lost on you if you were plugged into the machine—you wouldn’t know you weren’t really anyone’s friend.

Quite.

In my original comment to Matt Lowe on his blog I rather ineptly mentioned Fernando Pessoa. I was thinking about his semi-fictional narrator in The Book of Disquiet, who time and again prefers dreams and unreality to the Lisbon of his immediate environment. Opening his book at random I find this: “Direct experience is an evasion, or hiding place, for those without any imagination.” Pessoa, through his persona Bernardo Soares, is being deliberately provocative and paradoxical. For Soares, common reality is a form of escapism. He finds his true dwelling in an imagined world.

My challenge to the professor goes like this. In a world where most people’s reality is tainted with capitalistic opiates (of which his imaginary machine would be just one other), isn’t it better to dwell in the clean air of one’s own inner space? I read once that car advertisements aren’t so much to persuade you to buy a particular model, but to assuage your doubts after you’ve already bought it. So when you look at your car from the outside, or indeed from the inside, the ad tells you what kind of a person you are, and flatters you for possessing those virtues. The car may not please you, in fact the manufacturer doesn’t want it to please you more than a couple of years, but he wants you all the same to feel good about yourself for buying it.

I’d sooner be like Bernardo Soares, described by Richard Zenith, translator of Disquiet as

a prose writer who poetizes, a dreamer who thinks, a mystic who doesn’t believe, a decadent who doesn’t indulge. … The semi-fiction called Bernardo Soares … is an implied model for whoever has difficulty to adapting to real, normal, everyday life.

Postscript, 29th June ’18: Returning to this post several years later, I feel it only right to question whether I still consider Pessoa admirable in this regard. Is he not another escapist into fantasy, no better than the consumerist’s “happiness is tomorrow”, or the drug addict’s retreat? I decide to open his Book of Disquiet at random to see if he has an answer:

He tells me that he relates to what is in front of him. In Martin Buber’s terminology, the relationship is “I-You”, rather than “I-It”. Not only that, he speaks to his unknown reader in “I-You” terms as well. It’s mutual.

My illustration comes from http://www.opioids.com whose Home Page is prefaced with these words, attributed to Aldous Huxley:

“If we could sniff or swallow something that would, for five or six hours each day, abolish our solitude as individuals, atone us with our fellows in a glowing exaltation of affection and make life in all its aspects seem not only worth living, but divinely beautiful and significant, and if this heavenly, world-transfiguring drug were of such a kind that we could wake up next morning with a clear head and an undamaged constitution – then, it seems to me, all our problems (and not merely the one small problem of discovering a novel pleasure) would be wholly solved and earth would become paradise.”

LikeLike

“a mystic who doesn’t believe”

Like Meister Eckhart:

“I pray God to be rid of God.”

LikeLike

Thanks for the Xmas card. I'm glad you are enjoying life.

I hope you are both well and have a good 2011.

Sometimes I look at your blog and feel I am not learned enough to comment.

LikeLike

This comment has been removed by the author.

LikeLike

Vincent, Thanks you for the wonderful Christmas Gift, personally signed by you. It is a beautiful book written in an enrapturing literary style.

Hope to see a printed version soon.

Hope you are not delaying that because you want to make it perfect. It already is.

LikeLike

Happiness is the absence of fear.

LikeLike

Thanks Ashok! Now please clarify: are you, by this, placing your advance order for the printed version? If so, I feel encouraged.

Looking for your email address a few days ago, I stumbled upon a list of publications that you offer free as e-books, and somewhat less free as printed books. I only knew about one. You have been too modest to mention the others!

LikeLike

Rob, you are certainly learned enough to comment. When are you going to restart your blog, or start a new one? Thanks for your good wishes. Come and see us when you can!

LikeLike

Davo, you’re right. Absence of fear generates happiness. Sometimes I use another definition: happiness is when you wouldn't want to change a thing.

LikeLike

Yeah, Raymond, that Meister Eckhart was pretty radical – to the point of heresy, I should imagine. I had an anthology of his stuff once, I think they may have been sermons. It was exciting stuff.

LikeLike

There was a short story by an American writer named kurt Vonnegut about a happiness device. In the story, the device had an addictive quality that overtook the lives of those who used it and ultimately lead them to ruin. The “rent” for it was not much, but once someone succumbed to the addiction, their ability to earn any income at all was compromised. The idea that ultimate happiness must necessarily lead to ruin, I think may be worth exploring. What is the purpose of the infinitely happy fellow? How does reality look to him? Does he want to grow? Can he? Is he now settled into his eternity with nothing more to do other than feel joy? Has his story ended in a death of bliss?

Your Marx quote is very good. In America, we always hear that Marx said: “Religion is the opiate of the masses,” which is close. Unless we are studying Marx, we only get this fragment, which is less sympathetic to religion than the full quote. The incomplete quote made famous by our poor educational system sounds like a cynical indictment with no inherent ambivalence. The full quote is profound, rather than merely an aggressive reinforcement of a dogmatic position.

“To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up the condition that requires illusions.” That needs to be included, as the thought is not complete without it.

LikeLike

Yes, John, “the idea that ultimate happiness must necessarily lead to ruin” sounds ripe for exploring. My immediate thought is that Nature (I mean our human nature) provides us with carrot (happiness) and stick (misery) as a guide to our actions much more reliable than reason, which leads us to foolishness much of the time.

If you provide the donkey with an endless supply of carrots he won’t be any further use to his owner. The purpose of the carrot is to dangle it on a string in front of the donkey’s head. But that’s when we are talking of how to manipulate others.

I discover that in a country which approaches ever closer to peace, prosperity and stability (I speak of England) its people find just as many things to complain of in the world of society; but they are more trivial. Within the human psyche, the possibility for dysfunction and neurosis is endless, and not improved by a greater harmony in society at large.

But I am not sure how it is possible to compare the happiness of one person with another. One must not forget that happiness is not the label attached to a real thing, but a word, conventionally used in various contexts.

Let me declare that “there is no such thing as happiness”. But in so doing, I am implicitly declaring that Plato was wrong when he said that the idea embodied in a word exists in its ideal form, in some Platonic heaven.

Wittgenstein was right, but his battle has not yet been won in the public arena. It’s all too easy to get caught in the popular fallacy that abstract words have a meaning which transcends the way people use them.

If you take the word “honey” it has a real-life referent of course. But if you use “honey” as a metaphor for happiness, words are simply tools and pointers. A monkey pokes a stick into a hollow tree, trying to get honey. Imagine the word as a stick, and the hole in the tree as the human mind. You might get some honey that you can lick off the stick, or you might not. But the stick is nothing but a stick.

I think this is what our education systems need to clarify, before they even start talking about Karl Marx, or indeed the Bible.

LikeLike