Said Lehane, commenting on my last: “Would it also be sad to say that, through you, I’m kind of infatuated by this girl? Maybe on the way to falling in love with her.”

Therein lies a phenomenon not unknown in the world of fiction. If a reader may fall in love with a character in a story, what about the author? Certainly: just as Pygmalion fell in love with the statue he carved.

You may have noticed that my own tentative ventures into fiction lately here and here have had a common theme. A young woman lives with her parents, and meets a random stranger—me.

I write so much from impulse, I mean a place deeper than conscious recognition, that sometimes it’s only later that I understand why. Ten years ago, I wrote into existence my own Galatea. I recreated her from memory, every last detail. These days, I’m a better writer, knowing that the strength of literature lies in what’s left out.

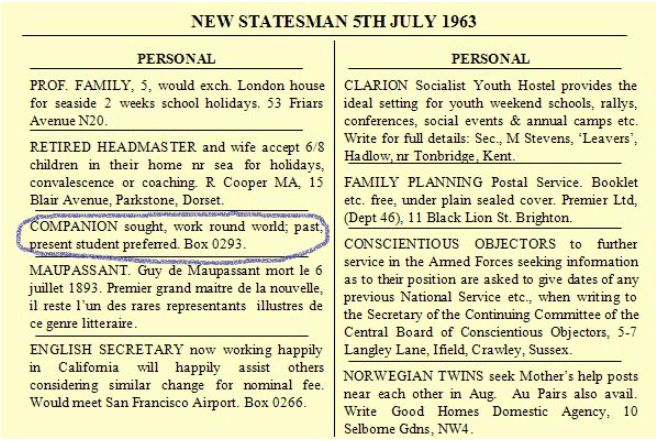

In July 1963, I’d just graduated as a Bachelor of Arts. But I’d lost everything else: my student status, friends, my girlfriend, any plans for the future. There was nothing on my landscape but a vast crater of loss. One day I bought a copy of the New Statesman at New Cross Tube Station, South East London, a few minutes after walking out of a training course for VSO (Voluntary Service Overseas). They were going to send me to what was then called French Guinea, in West Africa. I will not describe the particular humiliation which prompted my walk-out. At twenty-one, I lived in dreams. Apart from book-learning, which I was good at, my only achievement was to have survived five months in France and Italy on my own and penniless.

On the Tube, returning to my parents’ home in Staines, I saw this advert:

COMPANION sought, work round world; past, present student preferred. Box 0293.

That’s how I met my Galatea, aged nineteen. She was real, but it wasn’t till I wrote her story, in a late midlife crisis, that I became hopelessly enamoured. Thus I learned the power of writing.

Let that story, and the girl who inspired it, rest in peace.

Oh MY. A better beginning for a novel I've rarely read. I'm hooked and want to hear more!

LikeLike

Now, my dear Hayden, you put me in a quandary. What do you want, fact or fiction?

LikeLike

And then there is a third choice. You could dispense with fact and fiction, and just write the truth. I would enjoy that. (Not that the writer should do what her/his readers enjoy.)

LikeLike

Raymond, you are right. The truth is better than the fact. It is stranger than fiction – and stronger too.

The fourth choice is to let it be, and say no more. But since you want the truth, I was hoping I'd be asked for more.

LikeLike

The truth it shall be. Which means I have no idea where it will go; unlike fact, which is immutable, and fiction, which can be led on a string.

LikeLike

ah! I'm late coming back to the party here, but I'd be happy to see “truth” – for what I want from it is “story” and story isn't good unless it's true. And truth has nothing to do with the facts. And everything that is deeply true contains a wistful heart of Mystery…. a hint of maybes or what might have beens or somesuch lightly moored emotion.

(Just here from Rima Stanes' Into the Hermitage blog, and filled with mist and wonder)

LikeLike

What an astonishing site she has, Hayden! It lures you in. And it is so well done. I must go there again, devour it all. Meanwhile it's a distraction from other attractive tasks to which I'm committed.

Your comments on truth versus story are inspiring, and beam a light into a new realization, instigated by Raymond and elaborated by you, that “truth has nothing to do with the facts”, a statement which hints at a new definition of both words, and inevitably turns truth into a mystery, reachable only to the …

I don't know how to finish the sentence, but let us go for truth, together!

LikeLike

Truth, definitely, please! Truth does have something to do with the facts, in that truth and facts do not (I think) contradict one another. But truth is more than the sum of the facts. That's the challenge for those who wish to write truthfully.

Shall I place my order at Amazon now?

LikeLike

Sorry, Gentleeye and all. I've delved into the truth (my truth, I don't know of any other) and it gives me a hundred reasons to take this tale no further. I don't know what deeper truth could be extracted from it anyhow, to justify its fictionalisation into a novel. I wrote it badly ten years ago, and shared it with the man who Galatea eventually married. This inspired him to write his own memoir. So there are two accounts in existence which merged together could make up a biography spanning her life. I have decided it is properly respectful to keep them private.

My original intention was not to whet the appetite of readers, but indicate a common origin for a couple of stories which I published here recently: stories which actually give no hint of Galatea's.

LikeLike

well then, these comments rest as a tribute to style.

I still hold that, (in particular – starting with the sentence 'In July 1963,….') this was and is a lovely beginning for a story. You may excoriate me for saying it, but it has something of the robustness, the sense of what's there and what's missing, that makes such a fine beginning in Moby Dick. Yes, yes, many hate the novel, but I hold that if you just weed out some later portions the rest of it holds up magnificently, in particular the beginning. I KNOW yours and Melville's are not at all the same – if they were I'd settle back down for another look at Ishmael's travails and say nothing more.

I love broadness and specificity in a beginning. A sense of mystery that isn't addressed by the ample facts stated. The facts situate the event in a time and space, anchor it if you will. The mystery, still unaddressed, is the reason for reading. The sense that there is a story here, something with yet-hazy edges, but something that will eventually be as solid as the mundane detail that cloaks the beginning. That is what makes me draw a shawl around my shoulders on a cool evening, adjust the light and settle in for a good read.

LikeLike

Hayden, I'm indebted to you for the valuable feedback which is especially helpful at the moment. It's worth a post on its own.

LikeLike

Infatuation…the very point at where fact and fiction merges.

LikeLike

“Thou speakest wisely, Lehane, perhaps more than thou know'st,” spake Vincent, puffing sagaciously on his meerschaum, after a long silence in which loudest sounds were the ticking of the clock on the mantelpiece, and the settling of a charred log into the ashes, sending up sparks and a new tongue of flame which momentarily lit up the rows of books all around them which had gone invisible in the gathering crepuscule as they waited for the butler to turn on the light and bring in a tray of whisky and soda.

LikeLike