I’ve inherited a little volume, illustrated by the author, who was also my great-grandfather, entitled Dolomite Strongholds: the last untrodden peaks; published in 1894.

Don’t you love that Victorian prose, its characteristic style at once lofty and light, beloved of those who would make parodies of the works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, particularly those relating the cerebral and physical adventures of his great detective, Sherlock Holmes?

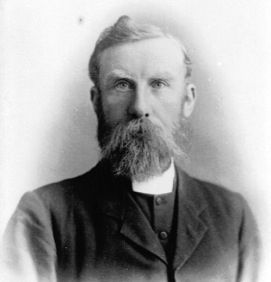

In fact I’d better cut to the chase and leave that style to the Rev. J. Sanger Davies, MA, Queen’s College Oxford and member of the Alpine Club. Let him speak for himself.

On the “Little Zinne Traverse”, the ledge seemed to me to be 100 yards long going, and 50 yards returning; let it go at the latter. The cliff above slightly overhung it, and, in fact, had protected the shelf. The drop from the edge was absolutely perpendicular, and the distance nearly 2,000 feet.

Of the breadth I am more certain, it nowhere exceeds fifteen inches on the flat, and the usual width was about nine inches. This, of course, would be six inches more than any rock climber would need if there had been any handhold.

But there was absolutely no safe hand-grip from end to end. The weathering had hollowed out the cliff which was generally of an even concave sweep, and the surfaces were all smooth and rounded out.

At two points the overhanging projection came down so low that one had to bend down to avoid it.

Yet the easy level of the path so plainly marked seemed to make it so simple that only by reflection can the full character of this long ledge be estimated; and many may pass over it without a thought of peril until some day of sad awakening.

Zsigmondi describes it as a “narrow” rocksill (Felsgesimse), and mentioned that “the inside wall lifted itself horribly smooth and perpendicular, while here and there in the split of the cliff were lumps of ice.”

Zsigmondi describes it as a “narrow” rocksill (Felsgesimse), and mentioned that “the inside wall lifted itself horribly smooth and perpendicular, while here and there in the split of the cliff were lumps of ice.”

The main feature of the place was not so much the apparent difficulty of threading it, as the long continued risk from the lengthened exposure to the perils of the way. Dangers which could not be provided against by the rope.

The ledge could not be crawled over, it was too long, and at places too narrow to allow for the width of the shoulders.

Its length precluded the possibility of using the shelf like a Telfer-wire for the elbows and arms while the body hung over the edge.

Worst of all the smoothness was so unbroken all the way that no “loca firma” could be chosen as a halting place whence the rope could be manipulated.

So we turned chest to the rock, and spreading out our arms edged along sideways, feeling our way but not able to grasp anything. This was exciting and more than I had bargained for. In the whole of my experience on the Dolomites this is the only passage that I should be unwilling to try again. Tastes will differ, but it seemed to me that in such a place no man can help his brother. The best of cragsmen can but hold his own while he keeps his balance, and he has nothing to spare at the best; a slipping foot, or a swimming head, or an uncertain eye, would settle the case of its possessor, and of his companions if roped to him.

The stiff upper lip, the studied understatement, the leisured clergyman whose language-skills were polished by a Classical education, all have flowed down the river of Lethe, leaving us with Health and Safety, gender-conscious grammar, mobile telephones which take photographs; and the faked exploits of cinema-stars.

I contacted the Alpine Club about the book, and received this reply:

Dear Ian,

We have his application for membership of the Alpine Club in 1893, some information on his later climbs, and a review of the book in the Alpine Journal. Unfortunately this is not very complimentary, but he makes a very spirited response. All this information is available in the Alpine Club Library and Archives.

The Library is usually open Monday/Tuesday/Wednesday, 10.00 – 17.00, and I work in the Archives on Tuesday and Thursday 11.00 – 17.00.

Regards,

— —

Hon Archivist

Alpine Club

I never made the trip to browse the archives, but a couple of years later my cousin Julian Rhys Williams did. So we now have a copy of the uncomplimentary review, Joseph’s spirited response and a few comments of my own based upon my own copy of the book.

I feel the same way about the blatantly unpolished, conversational style of my grandparents.

In spite of the fact that it must have sounded crude and unsophisticated, to the trained ear of the day, it sounds like music to mine.

LikeLike

You feel the same way? What way is that? That it is gone forever? Do you have recordings of their conversational style? It's interesting to compare with today, isn't it? Accents have changed a lot & other aspects of speech too.

LikeLike

I found a photo here of the Dolomites that may be relevant to the exploit described, by putting in Kleine Zinne to Google.

LikeLike

Yes, I do have some recordings of my grandfather. Some are recordings he made on vinyl. Apparently a service of some kind provided to New York City Tourists in his day. He would record his voice to send to his Mother when on extended trips.

I also have recordings of radio interviews and TV appearances he made.

This along with my own memories, some more recent than others, of my grandparents and their friends.

I have adopted some of the expressions of their day. They sound out of place, and are often misunderstood, but I enjoy keeping them alive.

LikeLike