Phineas Gage was swift, capable, responsible. He was physically fit and a leader of men. These qualities made him at the age of 25 a supervisor on a Vermont railroad construction project; and might have helped him rise through the ranks to a senior management position in that branch of engineering. But the smooth track of his life was shattered in a single instant.

Phineas Gage was swift, capable, responsible. He was physically fit and a leader of men. These qualities made him at the age of 25 a supervisor on a Vermont railroad construction project; and might have helped him rise through the ranks to a senior management position in that branch of engineering. But the smooth track of his life was shattered in a single instant.

A certain part of the terrain was littered with huge rocks. It had been judged less costly to blast them with gunpowder and build a straight railroad, than to detour round them. It was 1847 and Alfred Nobel being only 14 had not yet invented dynamite. The established blasting method was to drill a deep hole in the rock, pour in gunpowder, poke in a fuse (a long string made of gunpowder wrapped in paper) and cover with sand or clay. This had to be firmed up by tamping with an iron rod, so that the force of the exploding gunpowder would radiate in all directions, and not just back up the drilled hole, as from a gun.

On this particular occasion, Gage was preparing a number of blasting-holes. He found it a monotonous routine, something he could do with only half his attention. He was interrupted by a question from a fellow-worker, which took longer than anticipated to resolve. When he resumed, he forgot he hadn’t yet added sand to the current hole. He tamped the naked gunpowder with his iron bar. It sparked against the rock and set off the powder like a flintlock gun. The bar shot out with the force of a cannon-ball, passing through his skull. That single moment is the basis of his enduring fame.

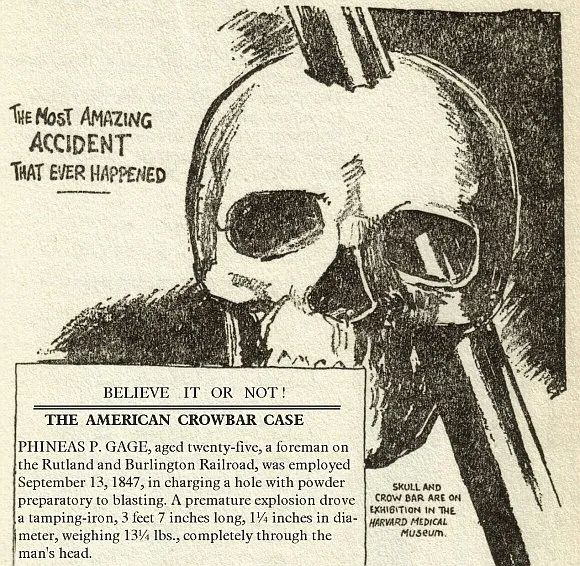

I learned about the incident when I was seven, or even six. I’d been sent rather young to a boarding school in Sussex*, more or less on the day my mother gave birth to my half-sister. My grandmother had taught me to read at four, soon after I’d arrived in England from Australia. I must have been a bewildered waif, but the Matron, Miss Woolgar, took me under her wing one day when I was poorly and sat me in her armchair with a big book to read: The Omnibus Believe It Or Not, by Robert Ripley. I was much impressed by the dramatic drawing, above. For nearly sixty years I’ve carried a mental image of Gage staggering along a track for assistance, the crowbar still in his head. In fact it had passed through swiftly and out the other side, taking bits of brain with it. In fact, as the accompanying text explains, it “made its exit at the junction of the coronal and parietal sutures …” At my age then, this fact passed over my head without lodging in my brain.

So when the story of Phineas Gage came up again in a book I’ve been recently reading by Antonio Damasio, it was familiar, like a Bible story woven into the fabric of one’s imaginative life. As for Damasio, my connection with him goes far beyond any academic interest in neuro-science. David Mickel put me on to him after my miracle cure from chronic fatigue syndrome. That illness was the great rock which blocked the track of my life. Must I curve around it, accepting its permanence? I didn’t know until a time when with all the force of my survival instinct I cursed it and rebelled against my fate. Dr Mickel’s therapy was the blasting process, miraculously sudden and effective, like a single explosion. Later, when I went to Edinburgh to study with Dr M himself, he recommended The Feeling of What Happens, by Antonio Damasio, whose earlier and more significant book I’m reading now: Descartes’ Error. It starts with an account of how Damasio’s wife Hanna, using Gage’s damaged skull preserved in the Harvard Medical School, made a computer simulation to work out which areas of his brain had been destroyed.

So when the story of Phineas Gage came up again in a book I’ve been recently reading by Antonio Damasio, it was familiar, like a Bible story woven into the fabric of one’s imaginative life. As for Damasio, my connection with him goes far beyond any academic interest in neuro-science. David Mickel put me on to him after my miracle cure from chronic fatigue syndrome. That illness was the great rock which blocked the track of my life. Must I curve around it, accepting its permanence? I didn’t know until a time when with all the force of my survival instinct I cursed it and rebelled against my fate. Dr Mickel’s therapy was the blasting process, miraculously sudden and effective, like a single explosion. Later, when I went to Edinburgh to study with Dr M himself, he recommended The Feeling of What Happens, by Antonio Damasio, whose earlier and more significant book I’m reading now: Descartes’ Error. It starts with an account of how Damasio’s wife Hanna, using Gage’s damaged skull preserved in the Harvard Medical School, made a computer simulation to work out which areas of his brain had been destroyed.

Gage was a living miracle, but it’s well-known that his survival had a dark side. All his basic faculties were intact but his personality was changed for the worse. To his friends he “was no longer Gage”. The detective work was to discover, comparing Gage with modern cases, the functions of the brain-cells destroyed by the passage of the tamping iron. We now know that they were from the region which processes emotion.

For centuries it had been assumed that emotion was the enemy of calm rationality but Damasio discovered that to be wrong. The new unemotional Gage was unable to make sensible decisions about how to run his life. He couldn’t get his old responsible job back. He was virtually unemployable after the accident, but not through what we normally think of as “brain damage”, i.e. loss of “intelligence”. You can read his doctor’s notes in this Wikipedia article, for an account of his personality change.

Why is the book called Descartes’ Error? The reasons are quite deep. I am just giving a summary here. Descartes, the “father of modern philosophy” saw mind and body as profoundly separate, with a single interface or bridge in the pineal gland. To Damasio, there can be no mind without body; no thinking without an awareness of the physical, whether it be our own body-awareness or an interaction with the outside world.

His idea, derived from neurological observation, changes everything. It makes religious theories obsolete: not completely wrong for they posited the existence of soul and God as the unseen source of the wonders perceived with senses. In Damasio I see a line between arid theology on the one hand and arid atheist science on the other.

Damasio is too erudite for me to explain further. I have understood his ideas not through the study of his books but the reintegration of my own self following a miraculous cure. I have had to find my own language to describe it. I have said in this blog that man is an animal, despite being overweighed with a huge intellect, like an elk with antlers, or a peacock with a gorgeous tail. I have discovered my own animal nature. My passions are governed by survival, my ecstasies induced by Nature, for I am its child, sucking at its teats. I am nourished by the paths that lead out from cities, and the ancientness of the open sky.

I was educated* with a bit of Latin and less Greek; forced into team games—soccer and cricket—as sole recognition of body. The headmaster viewed all deviant behaviour as incipient homosexuality. We must act as a pack of hounds, with him as chief huntsman. My rejection of competitive pursuits was seen as primitive, uncouth and shameful. I took refuge in solitary dreaming, out in the ploughed fields digging up fragments of clay pipes, discarded by the ploughman when they broke; or trying to bring down birds from the sky with a slingshot I’d invented, made from a springy stick with clay stuck to the end.

I tried in adult life to hunt with the pack. I allowed marriage and children to force me into well-paid desk-drudgery. I tried to find in religion, or rather its mystical soul, a language and guide for the unruly impulses I felt.

But how could religion work, when it was based on supremacy of soul over body; all life’s treasure leached away into the abstract realm? Religion was and is a cruel assault on a child’s mind. Like corporal punishment, its use has diminished here in England, to be replaced by the atheistical religion of science, capitalist economics and modern medicine; which is far worse. I’m for “spirituality”—except that it’s wrongly named—and always have been: but not for “beliefs”.

Phineas Gage was the first martyr and saint of neuro-science. Damasio’s work does more to explain what makes us tick than any psychology or theology I have read. But it can never make experiential religion or mystical awareness obsolete. For we possess the gift of direct knowledge, beside which science, for all its “evidence-based method”, is as speculative as theology.

Nothing in the laboratory tells us as much as our own primitive awareness. If someone tells of the visitation of an angel, or the voice of God heard on a lonely mountain-top, why should I not respect that? How else express an experience, but as it appears to you? Life is no less awe-inspiring, experience no less mystical, when we get closer to understanding the body and brain, whose soul is in every cell and neuron.

* Merrion House School, Sedlescombe

The above piece is dedicated with special thanks to Marc Lord who especially requested me to make the story of Phineas Gage into a post. It's my small contribution to July 4th, when Britain mourns the untimely loss of its best colony.

LikeLike

Why would any self respecting English person mourn the day one of their colonies broke away from the yolk of tyranny?

Really, you guys need a cold shower…

LikeLike

I’ve heard it said that Americans in general cannot get jokes based on irony. And I accept that they’ve simplified our spelling. But if you change yoke into yolk, you end up with egg on your face.

LikeLike

science is mechanics, struggling with the infinitely complex and changing. Holding too closely to the latest scientific announcement is no more than 'belief' as I see it. That said, I have no experience of angels and godly voices, and I've some of science, so am more inclined to throw in with the later.

I may regret commenting, but am fascinated by “yolk of tyranny.” Makes me muse on unborn life within tyranny, rather than the binding of “yoke.” That said, given the frequency w/ which I misspell… the 'yoke' is often on me.

LikeLike

This is an interesting piece, and I think it captures the essence atheist vs. believer argument. On one hand, our physiological aspect does display evidence-based forms of adaption in emotion, reaction, etc. However, our experiential aspect dictates that the physiological aspect is not the complete human being as you've pointed out here.

Your conclusion may very well be the final one, here Vincent: who are we to dictate to someone else what they should believe (i.e. religion, politics, etc)?

Even though I agree that 'spirituality' is an inadequate term to capture a true experiential existence of connectedness with life, the universe, and everything… I'm glad to know you're over here on the Dark Side. 😉

May the Force be with you.

LikeLike

Gerry, indeed, I have never met such an English person, self-respecting or otherwise. It was a flight of fancy, but thanks for the suggestion!

Hayden, I take your point about science versus inner promptings but I guess it's our nature to acquire beliefs and a measure of the maelstrom in the world today that beliefs are such a hot issue.

As for mis-spellings, these too are a feature of the age. My beloved works as a secretary, and being educated in Jamaica has a higher standard than the English in their own language, so she was deeply embarrassed yesterday when she sent out hundreds of copies of a document (which she had not typed herself) including the phrase “route cause”. Only one recipient noticed, and I advised her that few seem to care any more.

LikeLike

Timjamz, yes, point well spotted. I no longer believe in a detachable soul that has an after-life, in the “believer's” sense. I just think that science – or shall I say in this case Damasio – gives us new and more potent or timely metaphors with which to ponder existence.

But no matter the metaphors used, there will always be bits of experience left over unexplained.

LikeLike

in the last post you described about amala and kamala, or feral children. do they have emotion as we know the word? what if the same would have happened to one of those? would that make any difference to their lifestyle?

so, was gage close to his animal instinct which is i guess more welcomed.

LikeLike

No, Ghetufool. With Amala and Kamala I suppose they had developed wolf-behaviour at the most formative years and could not adapt otherwise.

With Gage, the damage to parts of his brain didn't make him closer to his animal instinct. It made him unable to cope with ordinary life. I'd never advocate that humans become closer to animal instinct, but to recognize that too much emphasis on the “new brain” at the expense of the “old brain” which we share with the animals can be harmful.

LikeLike

Hey! Glad I asked you to write on Gage, which is such an opportunity to muse upon the human mind, though not usually so lyrically and insightfully as you do here. Thank you for the nudge to get over here, and I wished you hadn't been so patient.

Actually, you see, it has been difficult to find you: when I click on your name in the comments section, your 4 blogs come up, and tho I've clicked on them all, there was a misleading constraint. In my browser, the comments pop-up window is rather small, and clicking through to a comment author link opens a second tab up in that little window without enlarging the whole. Clicking on a second blog link squishes yet another tab in and jumbles the formatting of its contents. So I had always been going to Reading Without Tears as your main blog.

Now that's set to right, so I'll link to Perpetual Lab off my main page. I will also steal this entire post, which has dazzling things to say about the seat of the soul. Elk antlers indeed, my friend.

LikeLike

Marc, there is a way around that Blogger constraint. If you click on the time at the bottom at the bottom of the post, you will get a version of the post with all its comments on a full page, not a small box. When you follow a link in that full page you will be able to navigate to it still in a full page.

Having got the technical bit out of the way, good to see you here and I understand that the choice of blogs is another barrier to getting here.

LikeLike

Someone found their way to this post recently as my blog statistics relate. Thank you, dear reader! I may republish — on social media: Facebook, Instagram, X and Bluesky..

LikeLike

[…] See also this post […]

LikeLike