Anno 1956 Aetat. 14

This post picks up my childhood memoirs from where Norfolk House (5): Fog on the Solent left off.

We moved to a 1930s semi-detached house, “Cherrydown”, 8 Parkhurst Road, Newport [here photographed August 2008—it hasn’t changed since 1956]. For the first few days, my bed was in the dining room, which my parents had wallpapered in maroon with gold fleurs-de-lys. My bed was covered with a striped African cloth, with threads of orange, green, maroon and gold. On the mantelpiece and windowsill were African carvings from family contacts in Kenya: a tortoise and a lion, in pale polished wood; also a conch and a giant cowrie shell. I was pleased with the exotic formality of the room. It had a spiritual feel. I was reading The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis at that time. Each night instead of doing prayer or meditation I performed a little ritual somersault on the springy bed. At a certain point it gave me a delightful dizziness in the head, which I suppose in a later era of psychedelics would be called an “altered state”. My sense of spirituality was physical. I felt good in my body and started to be more aware of it. I suppose this was a phase of puberty.

I was 14 and my mother was 46. It was the first time either of us had lived in a little suburban house with a nuclear family: just her, me and my stepfather. Perhaps it was a first for Blackett too, for in his first marriage, he and E had run a lodging house (Powys House, East Cowes). But soon after we moved in, my mother’s “hypochondria” started. She went into hospital for a gynaecological operation (D&C—perhaps it was an abortion?) and after that she would often complain of “fibrositis”—a pain in the shoulder. So Blackett would look after her, do much of the cooking and shopping, though he had a full-time job. My main chores were firelighting and cat care. Each morning in the winter months I had to rake out the ashes and sweep the front-room hearth clean. There was a way of keeping the fire “in” all night, by covering it with ashes to make it burn slowly. When that didn’t work I had to crumple newspaper, lay on sticks, place nuggets of coal carefully on top and make sure it lit successfully, before going to school. I always remembered Baden-Powell’s Boy Scout challenge: to light a fire with not more than two matches, but often failed.

The cat had to be shut up in the coal-store each night. It emerged gratefully when let out in the morning, its white paws and nose blackened by coaldust, which isn’t a good form of cat-litter, for it reacts chemically with urine to produce strong ammonia vapour. Furthermore, cat excrement isn’t fun to discover when you are shovelling coal in the dark. Then the cat had to be fed. Sometimes we bought Kit-E-Kat in tins, but we had a frugal budget and the usual expedient was to buy the cheapest cuts from the fishmonger: coley side-fins from behind the gills. These had to be boiled with stale white bread for about half an hour, stinking the house out and driving the cat frantic with anticipation. When cold it congealed into a jelly and lasted several days.

I got my own room before too long, the smallest bedroom with a window that looked out on flat fields with the Medina estuary in the distance. The house had three bedrooms but my mother insisted on her own, on the grounds that Blackett snored. Being a light sleeper was one of her hypochondrias. If some distant dog had barked in the night, she’d endlessly complain at breakfast about not having slept at all. I reckoned all this was to ensure Blackett made her the centre of his attention, and I wished he would resist, for all our sakes; but he indulged her devotedly, whilst muttering to himself.

My room was my domain and my retreat. I painted my bookcase in white gloss, also a wooden chest in red and white like a magic mushroom. Apart from books, my best companion was my own radio, for out of school I was a loner. It needed coaxing to pick up the various BBC stations. I had an aerial strung out over the back garden like a clothes line. In 1956 there wasn’t any teenage pop music, not that I knew of anyhow. But I knew songs like “Sixteen Tons”: “I was born one morning when the sun didn’t shine; I picked up my shovel and walked to the mine. I loaded sixteen tons of number 9 coal . . . sixteen tons and whadda you get? Another day older and deeper in debt.” These were songs for the whole family, not just rebellious teenagers. Next door was a family who each Sunday would listen to 3-way Family Favourites on the Light Programme, loud enough for me to hear in our garden. Servicemen stationed in Germany or Aden would send messages and song requests to their families back home, and vice versa; so that’s how I learned pop music: “Love and marriage”, “Buttons and Bows”, “Bell Bottom Blues”, “Never do a tango with an Eskimo” and so on.

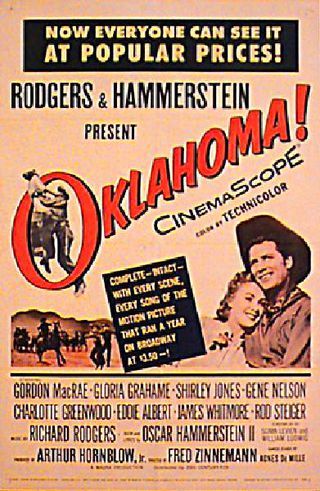

But one summer evening I chanced upon a radio performance of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!. I see now that a movie version had been released the year before, but I’d never heard of it. I had hardly heard of Gilbert and Sullivan either, till I found a gramophone record (an EP) with overtures: the Yeomen of the Guard on one side and Patience on the other. Such songs and tunes were to keep me going for months and years.

But one summer evening I chanced upon a radio performance of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!. I see now that a movie version had been released the year before, but I’d never heard of it. I had hardly heard of Gilbert and Sullivan either, till I found a gramophone record (an EP) with overtures: the Yeomen of the Guard on one side and Patience on the other. Such songs and tunes were to keep me going for months and years.

When I did discover pop, my favourites were Buddy Holly, Brenda Lee, Eddie Cochran, Fats Domino, the Everly Brothers: but I heard about Buddy in 1959, when he had already died, and Eddie in 1960 when he had also died. Their respective songs “It Doesn’t Matter Any More” and “Three Steps to Heaven” had become posthumous hits.

These days, it’s commonplace to link one’s childhood with children’s TV programmes and pop songs. But we didn’t have TV and my radio was a secret connection with a wider world. Pop was something I picked up second-hand, hearing imitations sung in the school playground, such as Presley’s “Hound Dog” or Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-A-Lula”. It was not part of my inner world and I had no curiosity as to where it came from. I do recall that there was some damage in a local cinema when Blackboard Jungle was shown, with Bill Haley’s “Rock around the Clock” being blamed for the hysteria. Till I checked just now, I thought the film itself was called “Rock around the Clock”; for I never went to see it being, I suppose, a head-in-the-clouds snob.

Vincent:

You said:

“I always remembered Baden-Powell’s Boy Scout challenge: to light a fire with not more than two matches, but often failed.”

This might be interesting to you. I live less than five miles in Florida from a road called Baden-Powell. There is a Boy Scout camp there (“Camp Shands”).

If you don't believe in the “coincidental” nature of God, then perhaps you won't understand how this is significant to me. BTW, I am adding this blog to my blogroll. I hope you don't mind.

Tim

LikeLike

Do you know where Baden-Powell is buried? Yes, it is near to my heart. He spent his last years in Kenya and is buried in Nyeri. :o)

http://www.scouting.org.za/seeds/paxtu.html

LikeLike

magical!

i was immersed reading this first class autobiography.

just one thing, you mentioned servicemen stationed in germany and india. and if i am not wrong, the year you associated is 1956.

but british left india in 1947. by 1956 only die-hard india lovers were here, no servicemen who miss their country.

[I subsequently corrected India to Aden—Ed.]

LikeLike

Music is real drugs to me. Ecstasy. Altered state. Pleasure and pain.

Music and also increase self-esteem and confidence. Choose the right songs.

LikeLike

There is something about radio that can have a much more intimate feel than the visual media that have displaced it in most content areas.

LikeLike

I think I agree with Paul about that difference, music by radio (no visuals), and otherwise (esp modern must-have videos), never thought of it before, but the difference is quite a difference to me, maybe that video has ruined music for me…of course video is quite different than attending an intimate (relatively speaking), live performance, no comparison to me.

I truly enjoy the humanity involved in your memoirs, I love the childhood memories and stories, they really connect with me, the child in me, still, it is like being home for a spell.

Real treasures Vincent!

LikeLike

My parents were both huge Buddy Holly fans so I must admit to having a soft spot for the bespectacled Lubbock rock n roller. And It Just Doesn't Matter Anymore was, and still is, my personal fave.

LikeLike