Please note that the Norfolk House story begins at “Nest of Dreams”, so I’ve numbered that “0”. Also that the mention of my “man-flu” affliction introducing yesterday’s piece was a warning that it would be rough. It’s edited extensively now.

In “Nest of Dreams” I referred to awakening sexuality. A boy, especially if he has come into contact with no girls, doesn’t necessarily associate his burgeoning virility with those giggling, teasing creatures. It doesn’t surprise me that some take the other direction and stay that way. In my case, wet dreams had always been accompanied by images of sweet feminine kindness. Now that I was sexual in daytime reality, girls played no part; but the garden surrounding Norfolk House was scene, and possibly arouser, of my solitary excitements. Shrubberies had overgrown till they were well-nigh impenetrable. I could squeeze into cool spaces where only scandalised mother-birds and their gaping hungry chicks knew I was there. I know that something moved me profoundly in those spaces because I recall wanting to paint water-colours of the leaves and buds. I also had a project to carve a piece of old oak into an oak-leaf shape. These things were never executed, being works of art in the mind’s eye only.

The kitchen at Norfolk house was a flat-roofed extension to the original building, projecting into a wooded area. A large oak, hollow at the roots, stood opposite the window: Wattie used to amuse himself throwing carving-knives at the rats which cavorted at the base of the tree. There were blue-jays, robins, cuckoos, red squirrels. One day I found a large dead pigeon whose insides were still moving. It was full of a heaving mass of maggots. Another day I found a rotting leathern bucket. Archaeological remains have always fascinated me, ever since I used to wander on ploughed fields at boarding-school whilst the other boys played football.

We had a few guests at the house. There was also one man who rented a small apartment with his own kitchen, which I discovered one day: a former scullery with plate-racks and draining-boards of wood, in the old style. He kept it neat, and used it mainly to make tea. When he found me there in what I considered my own secret place, he wasn’t upset with me for trespassing, but said I was welcome any time. He wasn’t over-familiar, or anything creepy, but I realised—or realise now—that a well-behaved 13-year-old boy can sometimes go anywhere and not be an intruder. (It was a bit like Lucy’s boarding-house in Australia, or the ship coming to England: you could wander about and feel welcome. Except for the time I had walked up the white-painted stairs to the ship’s bridge, and been brusquely sent away by a uniformed officer. That was the sole exception to my freedom as a 4-year-old.)

Breakfast was served to the boarders in a huge “saloon” overlooking the Solent, with a veranda outside. It faced North and wasn’t very warm. Each morning it was my job to light the little square stove with mica windowpanes, using paper, sticks (I had to cut logs and split them with a hatchet) and egg-shaped lumps of moulded coal-dust. If I lit this early enough, the guests who found the nearest tables could eat their bacon and eggs almost in comfort. But sometimes I tried several times to get the coal to light, and a guest would have to help me.

The guests were male apart from Mrs Dominie, a rotund widow. My mother was reduced to acting chamber-maid and was amused to find apple-cores and chocolate wrappers under her bed. I invented a soap-opera to amuse my mother and it went on for years, fuelled by such little incidents. According to its plot-lines, Wattie our chef cast a romantic eye upon Mrs Dominie, but she coyly resisted his advances. We introduced another character, Mr Dorey. He was a tenant at my grandparents’ house at that time, a deaf old man who was constantly expecting telephone calls. As soon as it rang, he would rush from his room and snatch up the receiver. it was one of those candlestick phones, where you hold the mouthpiece in one hand and the receiver in the other, as in the Marx brothers’ movies. “Dorey here!” he would boom. “D O R E Y. To whom am I speaking? Is that Slazenger? Eh? Eh? Eh?” It was an issue because in their courting days, Blackett had used to ring my mother long distance; and if Dorey answered, it took several expensive minutes to get “that old fool” off the line, for he was too deaf to realize it wasn’t his call. Dorey, in our soap opera, was a rival for Mrs Dominie’s affection. He would attempt to ring her up but Wattie would answer the ’phone and tell Dorey to clear off, whilst the poor widow sat lonely in her room, munching chocolate (it was always Toblerone) to sublimate her frustrations.

At school Mr Bell, our dapper art master, had introduced us to scraperboard (scratchboard in US) as an art medium. I must have been quite creative, because I started a strip cartoon, executed in scraperboard, of the Life and Loves of Mrs Dominie. I suppose many children are multifariously creative but without a focus and a mentor it’s hard to get the skill. In my case there was such a huge gap between fantasy and achievement that I tended to give up easily. In those days it never occurred to me to write: essays were drudgery. A picture is worth a thousand words, they say. But now I see it differently: a thousand words can express much more than a picture.

PS September 7th, 2022

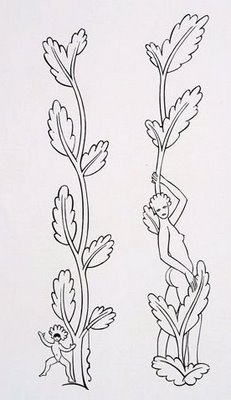

Further to the illustration above, my solitary sex might have been stimulated by this woodcut copied in 1934 from the original pencil drawing by Eric Gill:

I see what you mean, yes these kind of art pieces are powerful and full, more even than a picture, more practical for all, the artist and the owner or reader, most accessible and immediate and re-experienceable.

I love the flavours you are imparting thru the characters, and the growing understanding of yourself to yourself and to the reader, that in itself is more than worthy. You whet my appetite for the things you won't give me, tease me, almost show me, almost tell me, like the soap-opera and the scraperboard strip, not to mention the little details about the other characters that you don't indulge but almost do..

Add to that the reality of it, the factualness and certainty of the place and time, all adds up to a tasty treat that is addictive and hard to get, please, more if you please Vincent!

LikeLike

Wonderful! I, too, used to invent stories about those that surrounded me … only the animals were given personality and dialogue as well.

I absolutely adore your final lines on the written word vs. art. To echo Jim: “more if you please!”

LikeLike

Ah, Jim, that scraperboard strip, you see, if you want to know the facts, I only did it once, but it may have survived somewhere, though not with me. I also had another kind of soap-opera, actually it was a dish-washing opera. My half-sister is 7 years younger and she only used to come in the school vacations and so we didn't know one another that well. But we used to wash dishes together when she was old enough and i would tell her stories made up on the spur of the moment, and she liked “Bertie the Burglar”. I filled an exercise book with his adventures, and illustrations too done in coloured pencil. Bertie was a well-meaning criminal with a family to support and it was hard to make up stories in which his essential innocence was asserted and his wrongs righted, but together we managed it.

To me art is still a primitive response to the beauty of nature. I want to copy its magic in order to possess it for myself. The buzz is to achieve a likeness. When I started to paint in pastels (have hardly done any) I've always been inspired by dwellings on the side of hills: and now my study window looks out on to one such. But drawing and painting is such hard work!

What age were you when you stopped inventing stories? Have you actually stopped at all?

LikeLike

Intriguing for me in as much as I am also a keen photographer in addition to my love of story telling. I think the truth is some pictures can speak more than a thousand words, some words can say so much more than a whole series of pictures. The key, I believe, is to be able to identify the stronger. This is very appropriate to the life of a writer when deciding whether an *idea* is a short story, a poem, a novel, a screenplay, a stage play, etc, etc. We all know it very rarely works across all of these.

And to answer your subsequent question…the day *I* stop making up stories will be the day I draw my last breath I suspect.

LikeLike

Even in your reply, you describe a scene that was too, something in my life, the dishes and helper thing. The painting and drawing are hard work, but that is a zone, and in it, it comes automatically thru momentum, but is harder to achieve that as my age increases, still works tho Vincent.

My inventions, I think like for you, are always based on some facts and realities, sometimes they are all fact and real but leave details out, paintings are also like this for me usually anyway. Yours are great, keep writing Vincent!

LikeLike