I’ve thought about this question a few times recently in the night, and the answer would come promptly: what happens is what’s meant to happen happens is supposed to happen, just for me.

I’ve thought about this question a few times recently in the night, and the answer would come promptly: what happens is what’s meant to happen happens is supposed to happen, just for me.

I cannot know what it’s like for anyone else. That would be a matter of religious faith, which I’m not sure is a good thing. I only know that Alacrity is my invisible guardian angel, and exists as a metaphor in my life. But—only when I remember “her”.

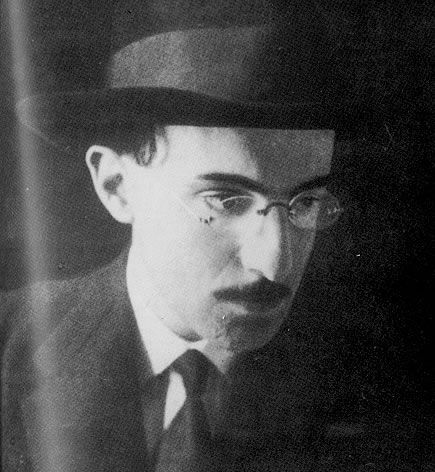

On this basis, I suppose, I was drawn last night to read something, and scanned the bookshelves above my pillow till my eyes alighted upon Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet, as translated by Richard Zenith. Opening it at random, I found these words starting on page 218:

What dreams do I have? I don’t know. I forced myself to reach a point where I’m no longer sure what I think, dream or envision. I seem to dream ever more remotely, about vague and imprecise things that can’t be visualized.

I have no theories about life. I don’t know or wonder whether it’s good or bad. In my eyes it’s harsh and sad, with delightful dreams interspersed here and there. Why should I care what it is for others? Other people’s lives are of use to me only in my dreams, where I live the life that seems to suit each one.

Thinking is still a form of acting. Only in sheer reverie, where nothing active intervenes and even our self-awareness gets stuck in the mud—only there, in this warm and damp state of non-being, can total renunciation of action be achieved. To stop trying to understand, to stop analysing. . . To see ourselves as we see nature, to view our impressions as we view a field — that is true wisdom.

… the sacred instinct of having no theories.. .

More than once, while roaming the streets in the late afternoon, I’ve been suddenly and violently struck by the bizarre presence of organization in things. It’s not so much natural things that arouse this powerful awareness in my soul; it’s the layout of the streets, the signs, the people dressed up and talking, their jobs, the newspapers, the logic of it all. Or rather, it’s the fact that ordered streets, signs, jobs, people and society exist, all of them fitting together and going forward and opening up paths. When I take a good look at man, I see that he’s as unconscious as a dog or cat, that he speaks and organizes himself into society through is different kind of unconsciousness, patently inferior to the unconsciousness that guides ants and bees in their social life. And as if a light had turned on, the intelligence that creates and informs the world becomes as clear to me as the existence of organisms, as clear as the existence of logical and invariable physical laws. On these occasions, I always recall the words of I can’t remember which scholastic: Deus est anima brutorum, God is the soul of the beasts. This marvellous phrase was the author’s way of explaining the certainty with which instinct guides inferior animals, which display no intelligence, or only a primitive outline of one. But we are all inferior animals, and speaking and thinking are merely new instincts, less dependable than others precisely because they’re new. So that the beautifully accurate phrase of the scholastic has a wider application, and I say, ‘God is the soul of everything.’ I’ve never understood how anyone who has stopped to consider the tremendous fact of this universal watch mechanism can deny the watchmaker, in whom not even Voltaire disbelieved.

I understand why, in light of certain events that have apparently deviated from a plan (and only by knowing the plan could one know if they have deviated from it), someone might attribute an element of imperfection to this supreme intelligence. I understand this, although I don’t accept it. And I understand why, in view of the evil that’s in the world, one might not acknowledge that the creating intelligence is infinitely good. I understand this, although again I don’t accept it. But to deny the existence of this intelligence, namely God, strikes me as one of those idiocies that sometimes afflict, in one area of their intelligence, men who in all other areas may be superior — those, for example, who systematically make mistakes in adding and subtracting, or who (considering now the intelligence that rules aesthetic sensibility) cannot feel music, or painting, or poetry. I’ve said that I don’t accept the notion of the watchmaker who is imperfect or who isn’t benevolent. I reject the notion of the imperfect watchmaker, because those aspects of the world’s government and organization that seem flawed or nonsensical might prove otherwise if we only knew the plan. While clearly seeing a plan in everything, we also see certain things that apparently make no sense, but if there’s reason behind everything, then won’t these things be guided by that same reason? Seeing the reason but not the actual plan, how can we say that certain things are outside the plan, when we don’t know what it is? Just as a poet of subtle rhythms can insert an arrhythmic verso for rhythmic purposes, i.e. for the very purpose he seems to be going against (and a critic who’s more linear than rhythmic will say that the verse is mistaken), so the Creator can insert things that our narrow logic considers arrhythmic into the majestic flow of his metaphysical rhythm.

I admit that the notion of an unbenevolent watchmaker is harder to refute, but only on the surface. One could say that since we don’t really know what evil is, we cannot rightfully affirm that something is bad or good, but it’s true that a pain, even if it’s for our ultimate good, is obviously bad in itself, and this is enough to prove that evil exists in the world. A toothache is enough to make one disbelieve in the goodness of the Creator. The basic error in this argument seems to lie in our complete ignorance of God’s plan, and our equal ignorance of what kind of an intelligent person the Intellectual Infinite might be. The existence of evil is one thing; the reason for its existence is another, The distinction may be subtle to the point of seeming sophistic, but it is nevertheless valid. The existence of evil cannot be denied, but one can deny that the existence of evil is evil. I admit that the problem persists, but only because our imperfection persists.