AUVERS 1890

“”He could not be persuaded to say when he would go. Not until May 16 did he wrench himself away, and then only after the sun had fallen and night had hidden the colours. In Paris, Theo, waiting anxiously day by day, suddenly received a telegram; Vincent was on the night train. Theo could not rest, imagining him having had an attack during the long journey, running amok, injuring himself or others. By the time he left for the Gare de Lyon the next morning Theo was a white-faced bundle of nerves.

To Jo at the window of their appartement (they were in the Cite Pigalle) he seemed gone an age; then an open fiacre drove into the courtyard below and two men waved up at her—Theo and the brother-in-law she had never seen. When they walked into the sitting-room she was astounded; the red-bearded man who came forward to greet her looked far healthier and stronger than Theo, his face was ruddy, his bearing confident and he was smiling cheerfully; he showed none of the signs of insanity she had feared—he did not even appear nervous. She could scarcely believe that he had come straight from an asylum where he had had fit after fit in the last few months.

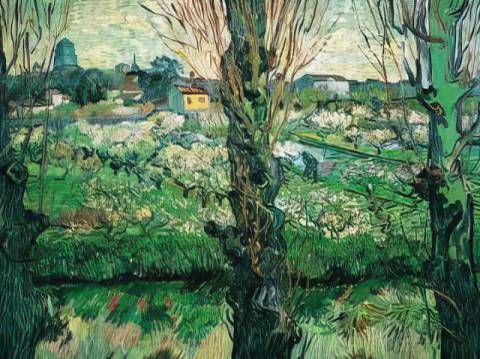

They looked at his namesake asleep in his cradle, then Theo fetched out Vincent’s paintings. Theo’s favourites had been framed and hung—De Aardappeleters over the dining-room mantel-piece, the Vue d’Arles and the first in the sitting-room—but piles of unframed canvases were stored in every available corner, under the bed, under the sofa, in the cupboard, and almost filled the little spare room. They were all taken out and spread one by one on the sitting-room floor; Vincent in his shirtsleeves, pipe puffing hard, knelt down staring hard at them with Theo bending over him; the place was in chaos but they talked happily and earnestly. The next morning Vincent was up early, examining his work again; he had never before seen it gathered together; he and Theo discussed it by the hour. Other painters dropped in—Bernard, Lautrec, Guillaumin. St Remy was never mentioned.

For a day or two Vincent seemed contented. In the morning he went out to buy olives—he had developed a passion for them in the south; all must eat them, he insisted—and he began a new self-portrait—his best. Jo marvelled at his normality; Theo, she began to think, had exaggerated his condition. Then all at once Paris, the visitors, the talk, the noise of the traffic, the lack of country air and colour—and perhaps something else that he could not acknowledge—affected him, and Jo detected unmistakable signs of abnormality—a sort of excessive form of the nerviness displayed by Theo from time to time; he became irritable, touchy, unbearably restless: he must go, he said; time was passing, he had much to do. He did not even try to discover if Gauguin were still in Paris—he dared not face this longed-for companion showing the slightest hint of nerviness. He left that day for Auvers, promising that he would return soon and make their portraits, and urging them to visit him when he had settled in.

At Auvers he called on Dr Gachet; he walked up the hill over-looking the Oise and climbed the terraced garden to the house, a massive building dimly lighted by tiny windows and in hope-less confusion, stuffed with antiques—”black, black, black!”—and looking and smelling like a museum. He found his host etching in a room rather like a dungeon. Gachet was in his early sixties, a widower, thin, nervous, emphatic. He specialised in diseases of the heart and travelled to Paris once or twice a week to give consultations, but his mind seemed to Vincent to be more on art than medicine; he was for ever painting or etching, he had been a friend of Courbet, Daumier, Daubigny and Manet; Cezanne, Pissarro and Guillaumin had all stayed with him in Auvers, and his house was filled with Impressionist canvases, most of them unframed and unhung.

He took Vincent into a large yard at the back of the house where ducks, chickens, turkeys, peacocks, cats and a goat, Henrietta, roamed amicably and he introduced him to his children, a girl of nineteen and a boy of sixteen. The boy, Vincent noticed with a sense of reassurance, had a distinct look of Theo. On the whole Vincent felt that he would get on well with Gachet. The man was mad, of course, as mad as he, but that was no handicap, a bond rather. They even looked alike—sufficiently so for Jo to comment on it when she saw them together; there seemed generally t0 be a curious family resemblance between the Gachets and Van Goghs.

Gachet had a passion for painting, oddly expressed though it was, and he had done much for it; when he settled in Auvers nearly twenty years earlier he had found Daubigny painting there, and after Daubigny’s death six years later he had tied hard and successfully to maintain Auvers as an art centre—aid tried, in fact, to do what Vincent had wished to do at Arles, to tempt men into the country to paint from nature and under a cl

ear light. He had thought in particular of the Paris painters and he had chosen well; Vincent was enraptured the moment he saw the little town—barely more than a village—sketch along one of the rolling hills, green and fertile, forming the Oise valley with the clear water running under the willows far below. It was a queer blend of styles; the eighteenth-century centre about the Maine, the clusters of rickety thatched cottages bordering the fields, and the newer outlying villas built by Parisians since the railway had been made, but Vincent liked them all—the thatch best of the lot, but the villas too, for they were set in flowery gardens and looked bright and cheerful in the sunshine. He could not wait to paint the place and, having resisted Gachet’s recommendation to an expensive inn, he settled at the cheapest he could find, the Cafe Ravoux in the Place de la Mairie. From his window he could see the Mairie opposite, and that pleased him too, for the little building was very much like the town hall at Zundert.

ear light. He had thought in particular of the Paris painters and he had chosen well; Vincent was enraptured the moment he saw the little town—barely more than a village—sketch along one of the rolling hills, green and fertile, forming the Oise valley with the clear water running under the willows far below. It was a queer blend of styles; the eighteenth-century centre about the Maine, the clusters of rickety thatched cottages bordering the fields, and the newer outlying villas built by Parisians since the railway had been made, but Vincent liked them all—the thatch best of the lot, but the villas too, for they were set in flowery gardens and looked bright and cheerful in the sunshine. He could not wait to paint the place and, having resisted Gachet’s recommendation to an expensive inn, he settled at the cheapest he could find, the Cafe Ravoux in the Place de la Mairie. From his window he could see the Mairie opposite, and that pleased him too, for the little building was very much like the town hall at Zundert.

He began at once with the first of his many views of Auvers, a study of thatched roofs with a foreground of corn and a back-ground of green hills. It differed from his landscapes at St Remy and the later ones at Arles; all morbidity, all exaggeration of colour and form disappeared, the colours were bright and gay, the study had the charm of a Japanese print, of a child’s painting, yet it was a mature and individual work and accurately reflected the state of his mind in the early days at Auvers. The mental disturbance of the last day or two at Paris was wearing off. He discussed his case with Gachet when he went up to the house again on Sunday (he was to spend every Sunday there, Gachet insisted), and his host was reassuring. If Vincent felt too de-pressed, something could be done to drive the depression away; but he thought that the change to Auvers might work its own cure.

Gachet was a deplorable advertisement for his skill as mental healer; on closer acquaintance his nerviness, his eccentricity and spells of low spiritedness were quite frightful—”there’s no doubt that old Gachet is very—yes, very much like you and me” Vincent told Theo—but he was kind, helpful and almost too ready to admire. And as at St Remy in the first weeks, the idea of a man afflicted like himself seemed to Vincent to be a positive comfort; he was not alone, he was actually companioned (per-haps exceeded) in peculiarity by, of all men, a doctor. Gachet ought to know the right treatment; Vincent was certainly feeling better, and was soon writing hopefully to Theo: “I begin to think I caught a disease peculiar to the south and that my coming here will be sufficient to get rid of the whole business.”

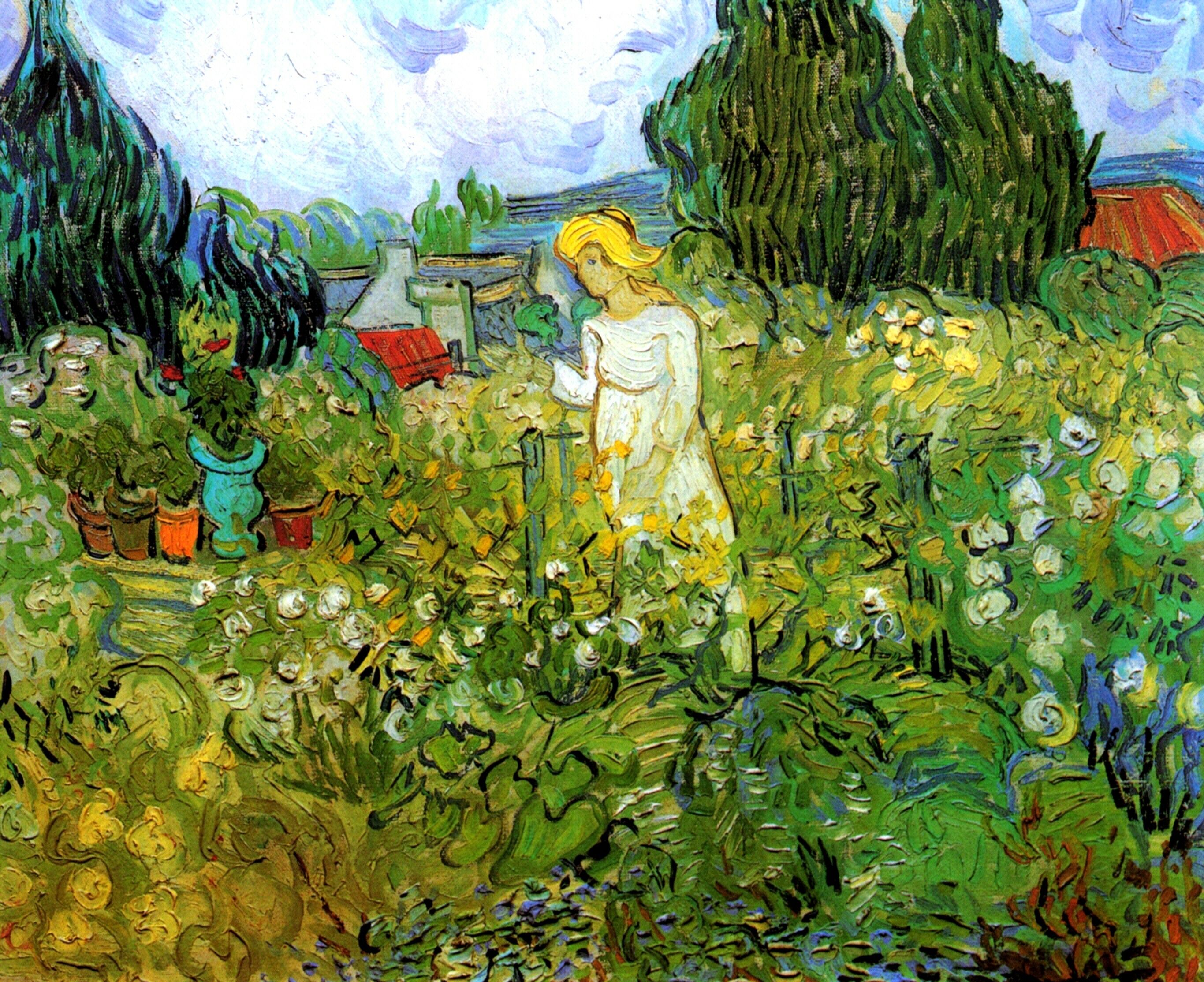

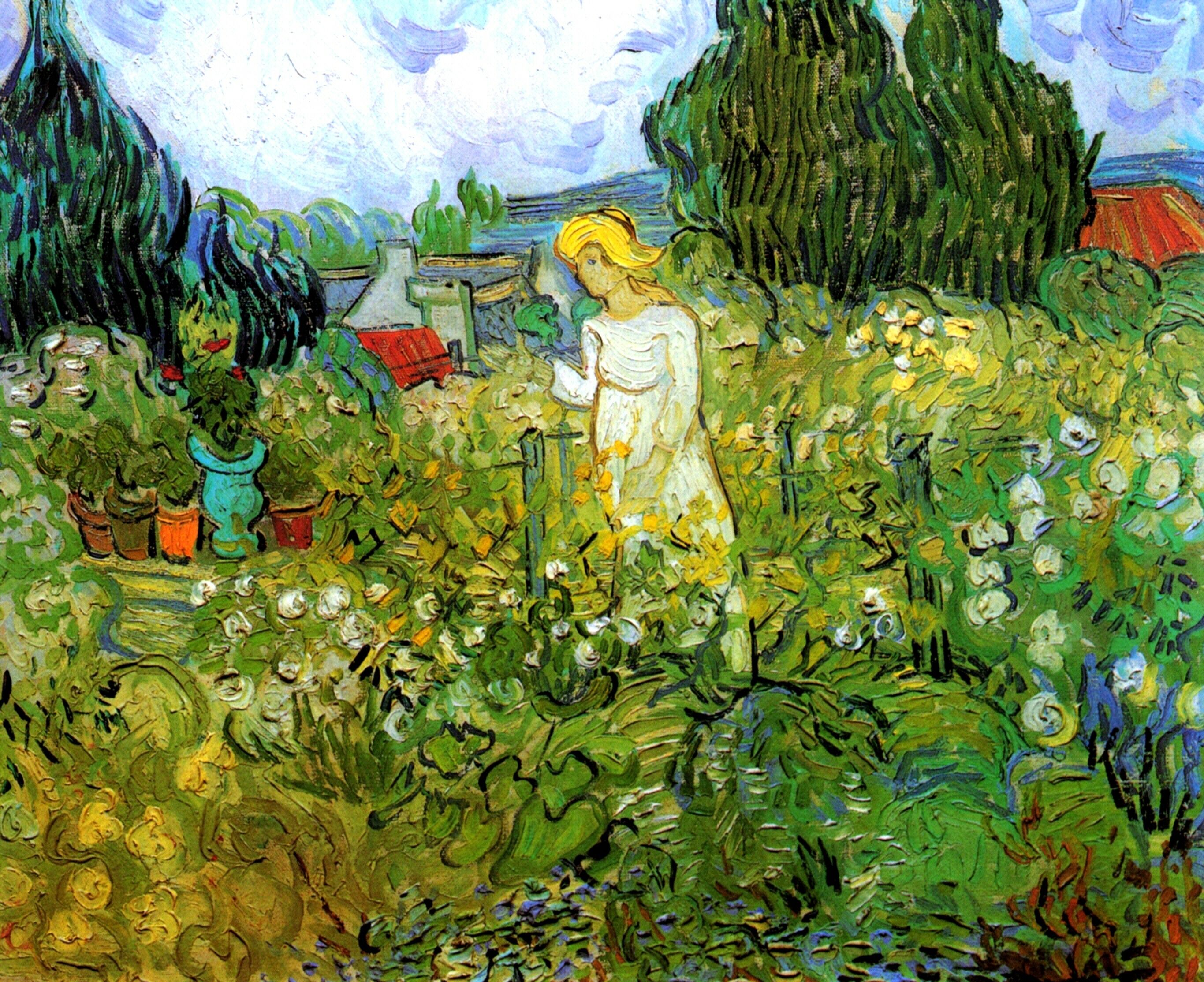

Such a thought was enough to change his whole attitude—a change best shown by his forbearance towards Gachet. In a sense those Sundays were absolute torture; he and Gachet struggled through two full meals of four and five courses because Gachet had old-fashioned notions of the manner in which to treat a distinguished guest; but Vincent not only perceived this, he endured it without a word. He had many kindnesses from Gachet; he was promised models beginning with the Gachet family, he was free to paint in the garden and immediately did so, making a study of Gachet’s daughter among the flowers and painting his Dans le Jardin du Dr Gachet, a work of particular interest in which the cypresses are treated as in the St Remy studies and the startlingly brilliant colours remind one of the Arles canvases, but which nevertheless conveys a sense of calm and order absent from both earlier periods as if—as was indeed the case—he has absorbed all the benefits of Provence while throwing aside the excessive emotionalism that Provence had raised in him. But these favours from Gachet would have been as nothing not so long ago to a Vincent asked to sit still for an hour or more, to stuff himself, and to listen to interminable reminiscences and rhapsodies. Now, chastened by his experiences and elated by the prospect of permanent release from them, he found a patience and a charity unknown in him before.

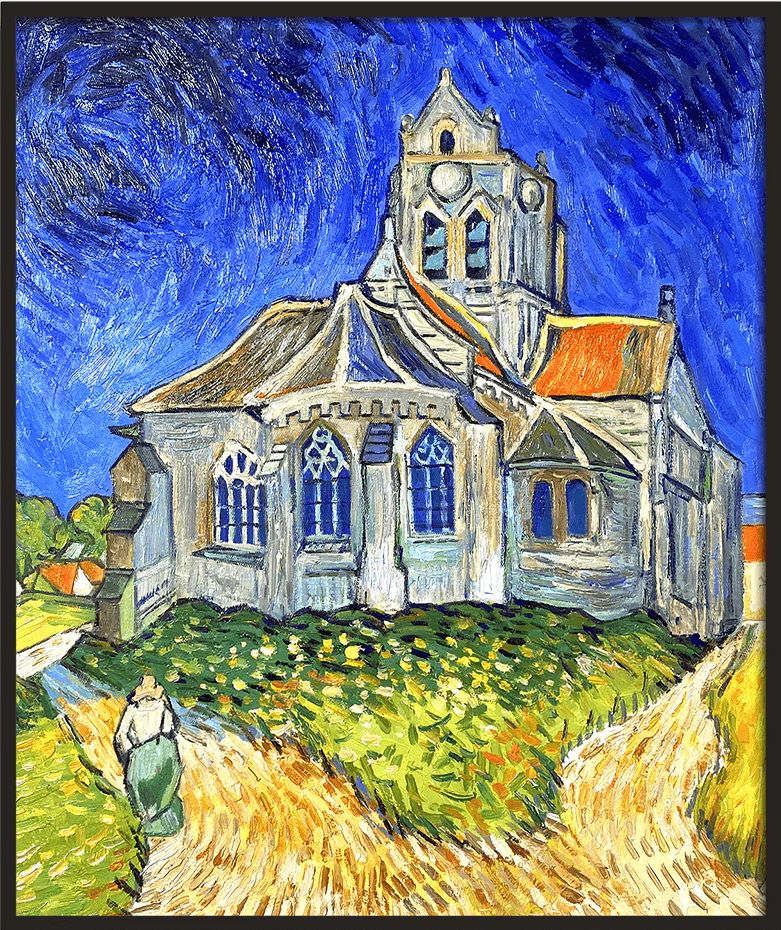

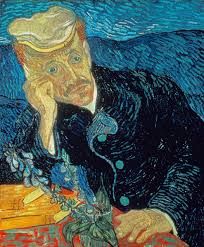

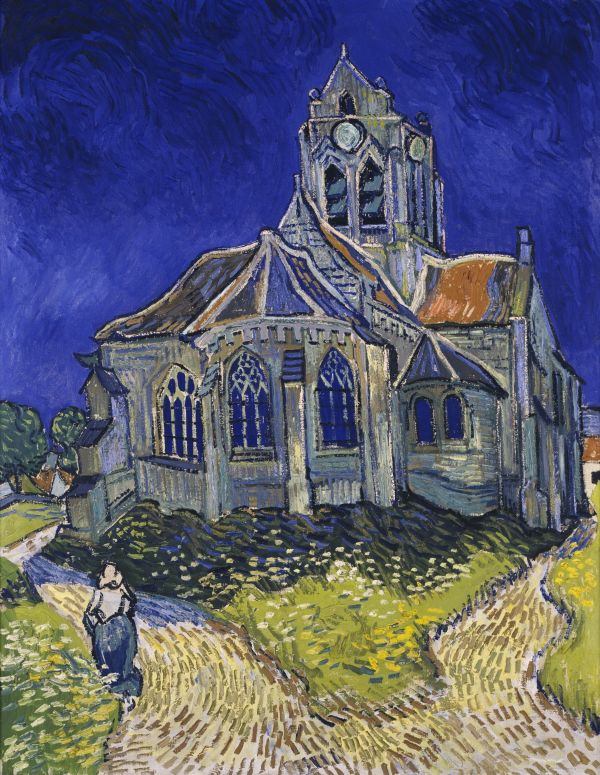

The first week he painted Gachet’s portrait—the portrait in which he wanted to portray “the heartbroken expression of our age”. Gachet, like Madame Ginoux, was an impatient sitter, and Vincent painted him as he had painted her, rapidly and with a masterly unity of design. Gachet was delighted—”he is absolutely fanatical about it”, Vincent told Theo—demanded another, and became from that moment a fervent admirer. He had seen Vincent’s studies in the cafe bedroom and prophesied a great future for him. This Vincent found embarrassing—he regarded himself still as in his infancy as a painter—but after years of neglect it was also undeniably gratifying. After all, Gachet was not an ignoramus, he had known, admired and collected the work of the Impressionists—if collection was the word for that haphazard assortment in odd corners. Vincent began to take heart, his premonitions to fade; he painted, light-heartedly for him, one confident picture after another, including Les Vaches after the engraving that Gachet had made with the study of Jordaens in mind but with a strength and mastery of colour unsuspected in the original. This picture he made with a speed unusual even for him; his , taken more slowly, was more impressive still—a remarkable example of his power to bestow individuality on the inanimate. He says of it—he wrote as usual though with a noticeable increase of confidence about all his work—”It is much the same as the studies I made of the old tower at Nuenen except that the colour is probably more expressive, more sumptuous” but as usual he did himself less than justice; colours and conception alike are inimitable. Elated by the progress he was making he was soon suggesting to Gauguin, who was back in Brittany, “It is very probable that —if you agree—I may join you for a month to make one or two seascapes, but specially to see you. Then we will try to do some-thing serious and studied—the kind of thing we should probably have done if we had been able to stay together in the south.” He had said out of the despair of St Remy, “I believe we shall work together again”, and that unlikely prophecy now seemed possible. The thought of Gauguin, never long out of his mind, and the joy of imagining himself at work with him once again plainly influenced his vision. He painted two studies of village children of which in particular is with one important exception the spit of Gauguin’s child studies in Brittany—the exception being that his children have not the appeal of Gauguin’s, being formidable rather than touching.

Gauguin’s reply was noncommittal—the inn was full, he said for he had no wish to have his “assassin” at close quarters again. Vincent was distracted momentarily from dismay by a visit from Theo and his family. Gachet invited them for the day and early in June Vincent met them at the station with a bird’s nest for his nephew, he carried the child to the Gachet house and took him round the yard, introducing him to all the animals. Theo had never seen him in such spirits and he too became bright and cheerful: Vincent had not exaggerated; the move to Auvers seemed to have cured him.

They lunched out in the garden where Vincent had made his portrait of Gachet, and in the afternoon Vincent took Theo and Jo round Auvers, pointing out what he had painted and what he must paint as soon as possible—Daubigny’s garden (his widow still lived in the village), the queer staircases from one street to another, the Maine, the fields and cottages, his landlord’s young daughter. Theo looked at the work in Vincent’s room: it was good and he felt pleased and proud: the Gachet portrait and L’ Arlésienne alone justified all the help so gladly given through the years. Surely Vincent’s hardships must be over: he was a very good painter, he would be a great painter, it was even possible that Gachet had not spoken wildly when, in a confidential whisper, he declared that Vincent was a giant among painters. “Every time I look- at his pictures I find something new. He’s not only a great painter, he’s a philosopher.”

Theo expressed his pride and pleasure to Vincent; he was charming, full of understanding—so much so that Vincent must have had the illusion that the Ryswyk accord had again been established.

Theo and Jo sat back relievedly in the Paris train that evening: a day with Vincent and not one jarring note! Theo said that he felt as if a new life was beginning for them all. Vincent, left by himself, felt his loneliness all the more for the company he had had, but he also felt the strength to face it. When his mother said how lonely she was in her old age, he replied: “I understand how you feel. I shall always be lonely too. My work is the only thing that keeps me contented.” In the next few weeks, he tried to live up to his words: he worked hard: he painted another portrait of Gachet, his son

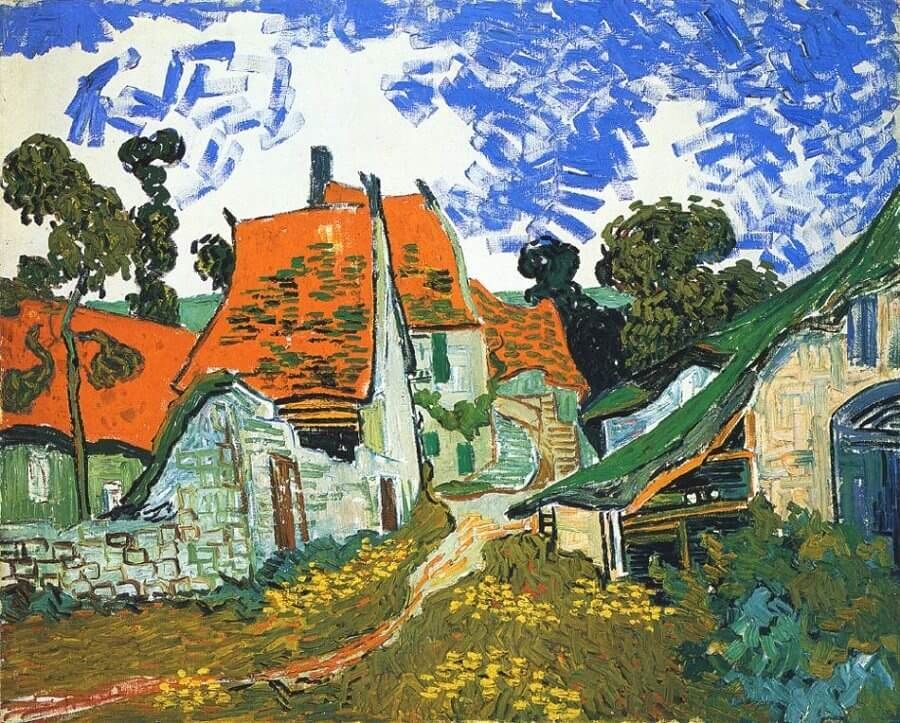

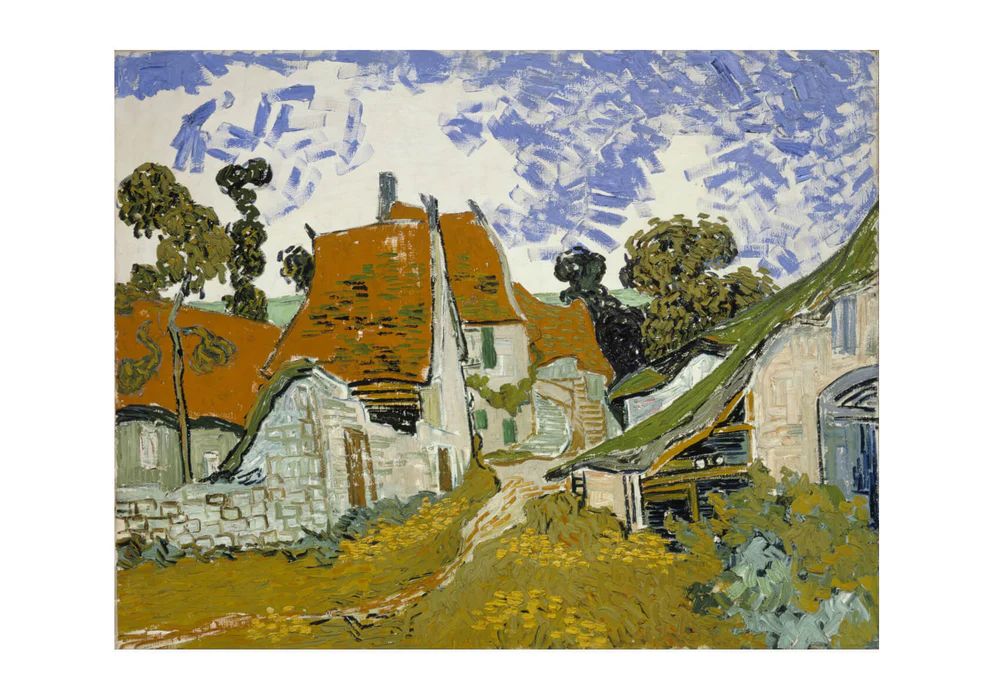

Theo, he painted three portraits of the sixteen-year-old daughter of his landlord, one of them a notable example of psychological I realism, he painted Daubigny’s garden and one landscape after another, culminating in the great Champ de blé sous un ciel bleu, and made his charming Paysage à Auvers as a companion picture to his painting of the Crau at Arles. The pictures poured out as though he had been freed from fear, as though he at last felt that the years of struggle were to have a triumphant end. His L’Escalier d’Auvers is a study in sinuosity years ahead of its time—a fascinating example of the curved line technique he had adopted at St Remy but used now without strain; he painted in his Jeune Fille Début a study, not of the usual field of corn, but of a “close-up” of the sheaf as ostensible background to the figure: he made in his Bouquet des Champs (unhappily impossible to reproduce satisfactorily in black and white) the finest of all his still-lives: “some thistles, corn, leaves of several grasses. One is almost red, the other very green and another yellowish.” What he did not say was that he had picked these things, grass, dock leaves, corn stalk, poppy, as he passed through the fields, had stuck them anyhow into an ochre jar and had painted rapidly a study of such beauty of colour, composition, such mastery of technique that the onlooker finds himself wordless. And finally he produced what is possibly his most striking canvas, the Rue à Auvers, the work not only of a great painter but—and the one contributes to the other—of a man at last unhaunted and free; the clear, bright colours and the irregular line of roofs with their hint of the fantastic leading him back to the cottages he had loved and had tried again and again to paint in the Netherlands. Always at this time he is talking of past times, at Etten in particular, as if the final flowering of his genius allowed his mind to return in happiness to those much loved scenes. He worked fast but not exhaustively. There was much to do, but there also seemed for the first time in his life no need for hurry except the natural eagerness of the painter surrounded by subjects. He was, after all, only thirty-seven; the brush at last “slips between my fingers like a bow on the violin”; perhaps the future was his. He had never felt so well nor so hopeful. His contentment was expressed in a letter to Wil—his first from Auvers because_ he explained, he had been so busy. He wrote enthusiastically “It keeps me contented.” In the next few weeks he tried to live up to his words: he worked hard: he painted another portrait of Gachet, he painted his son, he made a study of Marguerite Gachet at the piano that brought a cry of “admirable!”

it’s unfinished & likely to stay that way, but you can buy a copy of the book very cheaply from eBay here

LikeLike