By definition the past is lost. We can’t live there any more; only in memory, imagination and books. To my simple mind, a progressive is one who’s excited by plans for the future, whereas a conservative takes inspiration from aspects of the past. In my own case, I concur with Robbie Burns that the best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft agley. We may rough-hew them, as another poet says, but destiny, too, takes a hand in the shaping.

By definition the past is lost. We can’t live there any more; only in memory, imagination and books. To my simple mind, a progressive is one who’s excited by plans for the future, whereas a conservative takes inspiration from aspects of the past. In my own case, I concur with Robbie Burns that the best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft agley. We may rough-hew them, as another poet says, but destiny, too, takes a hand in the shaping.

Everyone can clearly see a mixture of good and bad in the past. The present is no less mixed, but which is good? Which is bad? Mud is slung between one entrenched dogma and the other. Meanwhile the future creeps up on us, day by day. May it be shaped by well-meaning hearts! May they give one another space to breathe!

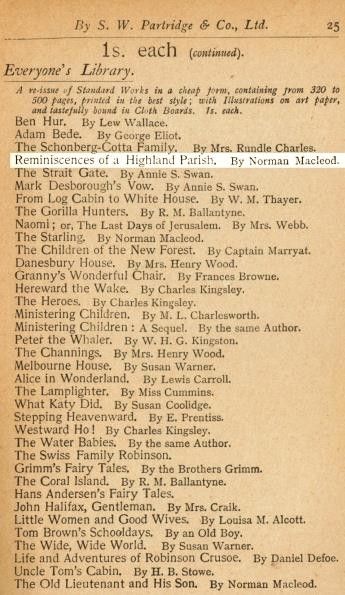

I bought an old book in Oxfam, a dollar at today’s exchange. It was first published in 1867; my edition is about 1910. It has a chapter on the Tacksmen*, from which I’ve taken some excerpts. Its author describes a Highland way of life already eroded and all but wiped out since the tour made by Dr Johnson with James Boswell in 1773.

I think there is more here than history, coloured by rose-tinted nostalgia; but I don’t want to colour it further with my own ideas. . . .

The Tacksmen at that time formed the most important and influential class of a society which has now wholly disappeared. . . . In no country in the world was such a contrast presented as in the Highlands between the structure of the houses and the culture of their occupants. The houses were of the most primitive description ; they consisted of one story—had only what the Scotch call a but and ben ; that is, a room at each end, with a passage between, two garret rooms above, and in some cases a kitchen, built out at right angles behind. Most of them were thatched with straw or heather. “The house and the furniture,” writes Dr Johnson, “ were . . . always nicely suited. We were driven once . . . to the hut of a gentleman, when, after a very liberal supper, I was conducted to my chamber, and found an elegant bed of Indian cotton, spread with fine sheets. The accommodation was flattering; I undressed myself, and found my feet in the mire. The bed stood on the cold earth, which a long course of rain had softened to a puddle.” But in these houses were gentlemen, nevertheless, and ladies of education and high-breeding. . . .

One characteristic of these tacksmen . . . was their remarkable kindness to the poor. There was hardly a family which had not some man or woman who had seen better days, for their guest, during weeks, months, perhaps years. These forlorn ones might have been very distant relations, claiming that protection which a drop of kindred blood never claimed in vain; or former neighbours, or the children of those who were neighbours long ago ; or, as it often happened, they might have had no claim whatever upon the hospitable family beyond the fact that they were utterly destitute, yet could not be treated as paupers, and had in God’s providence been cast on the kindness of others, like waves of the wild sea breaking at their feet Nor was there anything “ very interesting” about such objects of charity. One old gentleman-beggar I remember, who used to live with friends of mine for months, was singularly stupid, and often bad-tempered. . . .

Now this hospitality was never dispensed with a grudge, but with all tenderness and the nicest delicacy. These “genteel beggars” were received into the family, had comfortable quarters assigned to them in the house, partook of all the family meals ; and the utmost care was taken by old and young that not one word should be uttered, nor anything done, which could for a moment suggest to them the idea that they were a trouble, a bore, an intrusion, or anything save the most welcome and honoured guests. This attention, according to the minutest details, was almost a religion with the old Highland “gentleman” and his family. The poor of the parish, strictly so called, were, with few exceptions, wholly provided for by the tacksmen. Each farm, according to its size, had its old men, widows, and orphans depending on it for their support. The widow had her free house which the farmer and the “ cottiers” around him kept in repair. They drove home her peats for fuel from “ the Moss;” her cow had pasturage on the green hills. . . .

The parish . . . which once had a population of 2200 souls, and received only £11 per annum from public (church) funds for the support of the poor, expends now under the Poor-law upwards of £600 annually, with a population diminished by one-half, but with poverty increased in a greater ratio. This, by the way, is the result generally, when money awarded by law, and distributed by officials, is substituted for the true charity prompted by the heart, and dispensed systematically to known and well-ascertained cases, which draw it forth by the law of sympathy and Christian duty. I am quite aware how poetical this doctrine is held to be by some political economists, but in these days of heresy in regard to older and more certain truths, it may be treated charitably.

The effect of the poor-law, I fear, has been to destroy in a great measure the old feelings of self-respect which looked upon it as a degradation to receive any support from public charity when living, or to be buried by it when dead. It has loosened also, those kind bonds of neighbourhood, family relationship, and natural love which linked the needy to those who had the ability to supply their wants, and whose duty it was to do so, and which was blessed both to the giver and receiver. Those who ought on principle to support the poor are tempted to cast them on the rates, and thus to lose all the good derived from the exercise of Christian almsgiving. The poor themselves have become more needy and more greedy, and scramble for the miserable pittance which is given and received with equal heartlessness.

The temptation to create large sheep-farms has no doubt been great. Rents are increased, and more easily collected. Outlays are fewer and less expensive than upon houses, steadings, &c. But should more rent be the highest, the noblest object of a proprietor ? Are human beings to be treated like so many things used in manufactures? Are no sacrifices to be demanded for their good and happiness?  Granting, for the sake of argument, that profit, in the sense of obtaining more money, will be found in the long run to measure what is best for the people as well as for the landlord, yet may not the converse of this be equally true—that the good and happiness of the people will in the long run be found the most profitable?

Granting, for the sake of argument, that profit, in the sense of obtaining more money, will be found in the long run to measure what is best for the people as well as for the landlord, yet may not the converse of this be equally true—that the good and happiness of the people will in the long run be found the most profitable?

In the meantime, emigration has been to a large extent a blessing to the Highlands, and to a larger extent still a blessing to the colonies. It is the only relief for a poor and redundant population. The hopelessness of improving their condition, which rendered many in the Highlands listless and lazy, has in the colonies given place to the hope of securing a competency by prudence and industry. These virtues have accordingly sprung up, and the results have been comfort and independence. A wise political economy, with sympathy for human feelings and attachments, will, I trust, be able more and more to adjust the balance between the demands of the old and new country, for the benefit both of proprietors and people.

*tacksman (Scottish):One who holds a tack or lease of land . . . esp. in the Highlands, a middleman who leases directly from the proprietor of the estate a large piece of land which he sublets in small farms.

Um, the absolute arrogance of th “English” who tend to forget that the “Nation’ of the British Isles was forged by many and successive ‘invasions’. So, let me go back a bit (and yes, relying on ‘written’ history -very little is known about the ‘original’ inhabitants (at this point will have to skip past the Angles, Jutes and Saxons who also left a cultural legacy – the Romans – and yep, at some point in history decided that it wasn’t worth hanging about – but left a lasting legacy. Who next? O, the Normans. From what we now know as France. 1066CE (CE denotes ‘christian era’ and BCE denotes ‘before christian era’. Apologies, but cannot view history as ‘before Christ or ‘after christ ” Anno Domine”? That is an incredibly powerful subliminal message reminding us that the Roman Imperium has never been defeated.

O, where was i .. ah, the Normans … some might say that they brought ‘civilisation’ and ‘sophistication’ to the British Isles .. but some might say that they were, basically – thugs on horseback.

I could go on, and on … but the basic question remains … what’s changed?

LikeLike

“The arrogance of the English”, eh? That’s a sweeping statement, asking to be swept in its turn. Not that I deny it. Perhaps some are born to be humble, others are born to have something worth being arrogant about. Be grateful for your English ancestry, why not? Nothing to be ashamed of.

LikeLike

My English ancestry? Um, OK, am suitably humbled. Yessir, nossir (bows head and tugs the brim of cap).

LikeLike

Seriously, Vincent, ‘recorded’ Australian History is what; 250 years old? Who really knows what this Island continent will be like 2000 years hence.

LikeLike

Also, we really have to consider the reality of geography. ‘Asia’ is closer than “Europe”.

LikeLike

… and not even in the Northern Hemisphere – with all it’s squabbles and troubles (you can delete this bit .. heh.)

LikeLike

I can delete all the bits, when the fancy takes . . .

As for being humbled, when there is cause for shame, one should atone. At other times find reason to be proud, whoever one is, and of whatever inheritance or geographical origin.

To one’s enemies pride may be called arrogance.

LikeLike