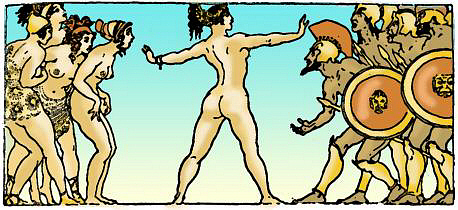

Originally performed in classical Athens in 411 BC, it is a comic account of one woman’s extraordinary mission to end the Peloponnesian War. Lysistrata persuades the women of Greece to wiRthhold sexual privileges from their husbands and lovers as a means of forcing the men to negotiate peace—a strategy, however, that inflames the battle between the sexes.

I love this play, with its strong, brave & inventive language reminiscent of Shakespeare. In many ways it seems quite modern, give or take a century. We can see in it how much of our Western culture comes from the Greeks, long before the invention of a sin-obsessed Christianity.

As someone who reacts negatively to the over-earnest bleating of some feminists, with their strong whiff of misandry, I find myself applauding Lysistrata and her gang of militant women protesters. Aristophanes carries the whole thing off with bawdy humour. It’s rumbustious good fun, even the threatened violence and ritual humiliation of the ridiculous old men, who are left none the worse apart from having pisspots poured on them. It’s satire targeted at its own contemporaries yet survives the centuries. I imagine some of its original audience squirming but unable to take offence out loud, for fear of being identified with the laughing-stocks depicted on stage. Given a good translation *, many of the innuendoes can be picked up by a modern audience without help of notes.

There is much relevance for our age. I think of various trouble-spots, and suspect the heroine’s household metaphors still have something useful to say:

MAGISTRATE

How, may I ask, will your rule re-establish order and justice in lands

so tormented?

LYSISTRATA

Nothing is easier.

MAGISTRATE

Out with it speedily–what is this plan that you boast you’ve invented?

LYSISTRATA

If, when yarn we are winding, it chances to tangle, then, as perchance you

may know, through the skein

This way and that still the spool we keep passing till it is finally clear

all again:

So to untangle the War and its errors, ambassadors out on all sides we will

send

This way and that, here, there and round about—soon you will find that the

War has an end.

MAGISTRATE

So with these trivial tricks of the household, domestic analogies of

threads, skeins and spools,

You think that you’ll solve such a bitter complexity, unwind such political

problems, you fools!

LYSISTRATA

Well, first as we wash dirty wool so’s to cleanse it, so with a pitiless

zeal we will scrub

Through the whole city for all greasy fellows; burrs too, the parasites,

off we will rub.

That verminous plague of insensate place-seekers soon between thumb and

forefinger we’ll crack.

All who inside Athens’ walls have their dwelling into one great common

basket we’ll pack.

Disenfranchised or citizens, allies or aliens, pell-mell the lot of them

in we will squeeze.

Till they discover humanity’s meaning…. As for disjointed and far

colonies,

Them you must never from this time imagine as scattered about just like

lost hanks of wool.

Each portion we’ll take and wind in to this centre, inward to Athens

each loyalty pull,

Till from the vast heap where all’s piled together at last can be woven

a strong Cloak of State.

MAGISTRATE

How terrible is it to stand here and watch them carding and winding at

will with our fate,

Witless in war as they are.

LYSISTRATA

What of us then, who ever in vain for our children must weep

Borne but to perish afar and in vain?

MAGISTRATE

Not that, O let that one memory sleep!

LYSISTRATA

Then while we should be companioned still merrily, happy as brides may,

the livelong night,

Kissing youth by, we are forced to lie single…. But leave for a moment

our pitiful plight,

It hurts even more to behold the poor maidens helpless wrinkling in

staler virginity.

Isn’t it delightful? Or perhaps one needs to read the whole thing. And if one has a sense of life in England, Europe or the States before women’s suffrage, one will appreciate the frustration of women excluded from affairs of state.

Lysistrata by Aristophanes, translated by Jack Lindsay† & illustrated by Norman Lindsay‡—free download from Gutenberg

As further reading, I recommend an essay on a single line from the play: The Lioness & the Cheese-Grater

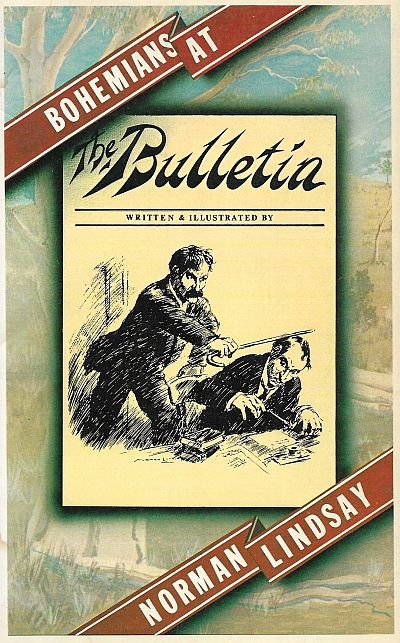

‡ It was a delight to rediscover Norman Lindsay (1879-1969), whose talents as a writer, as well as a brilliant illustrator, are well showcased in Bohemians at the Bulletin, which in prose and drawing recalls the Australian writers he knew in Sydney at the dawn of the 20th century; writers I’ve enjoyed—Steele Rudd, Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson (famous for “Waltzing Matilda”), Tom Collins (Such is Life) and Miles Franklin (My Brilliant Career), which was also made into a film. Nine films have been based on his novels.

† Jack Lindsay (1900-1990) was a son of Norman Lindsay. His translation of Lysistrata was published in 1925.

I feel a special affinity for Australian literature, doubtless arising from the country of my birth and paternity. It occurred to me that my readers would not likely share this affinity. Then oddly, as if in answer to this thought, I opened at random a poem by Fernando Pessoa called Oxfordshire, which ends with the enigmatic line

You can be happy in Australia, as long as you don’t go there

—which reflects my attitude exactly.

My new discipline of posting daily seems to be falling into a literary groove. I didn’t push it in deliberately, let it stay there or climb out of its own accord. I shall simply keep writing and see what happens

It’s a great feeling when an old or even ancient story feels relatable.

“You can be happy in Australia, as long as you don’t go there.”

Ha! It’s kind of like they took that old saying, “It’s a great place to visit, but I wouldn’t want to live there,” one step further and said, “Well, why even bother with the visit?”

LikeLike