This could describe me:

While out walking I’ve formulated perfect phrases which I can’t remember when I get home. I’m not sure if the ineffable poetry of these phrases belongs totally to what they were (and which I forgot), or partly to what they weren’t. [from fragment 399 of The Book of Disquiet, by Fernando Pessoa, tr. Richard Zenith]

This too:

I hesitate in everything, often without knowing why. How often I’ve sought—as my own version of the straight line, seeing it in my mind as the ideal straight line—the longest distance between two points. I’ve never had a knack for the active life. I’ve always taken wrong steps that no one else takes; I’ve always had to make an effort to do what comes naturally to other people. [from fragment 399 of The Book of Disquiet, by Fernando Pessoa, tr. Richard Zenith]

And I wish I’d been able to think clearly enough to say this:

It is in the nature of beginning that something new is started which cannot be expected from whatever may have happened before. This character of startling unexpectedness is inherent in all beginnings and in all origins. Thus, the origin of life from inorganic matter is an infinite improbability of inorganic processes, as is the coming into being of the earth viewed from the standpoint of processes in the universe, or the evolution of human out of animal life.

. . .

Action and speech are so closely related because the primordial and specifically human act must at the same time contain the answer to the question asked of every newcomer: “Who are you?” [from “The disclosure of the agent in speech and action” in The Human Condition, by Hannah Arendt]

All the same, I do try to say things for myself, such as this:

In the spring and summer of this year 2006 I opened all my senses, not just the usual five, to Nature. I’m searching here for an adequate word, but Nature will have to do. I exposed myself to the sublime and intricate world of non-human life, its pathos and grandeur. [my post on The Human Condition]

But most of the things I want to say, and haven’t the ability to express, have been said by others, and I discover them in the authors I admire:

ADMIRATION, n. Our polite recognition of another’s resemblance to ourselves. [from The Devil’s Dictionary, by Ambrose Bierce.]

Sometimes I read things that have special meaning for me, perhaps adrift from the author’s intention:

. . . every animal is in the world like water in water.

. . .

Nothing, as a matter of fact, is more closed to us than this animal life from which we are descended. Nothing is more foreign to our way of thinking than the earth in the middle of the silent universe and having neither the meaning that man gives things, nor the meaninglessness of things as soon as we try to imagine them without a consciousness that reflects them. [from first chapter, “Animality” of Theory of Religion, by Georges Bataille, tr. Robert Hurley]

*********

I’ve lived as a rolling stone, more Sisyphus than Jagger, and if I have gathered any moss it has been in the form of books: the love of them and sometimes the possession. In my youth I’d transport them in trunks and lay them out somewhere at my temporary destination; till a divine madness, as it seemed then, overtook me in 1972 & I gave away all I possessed. In recent years I’ve been avidly buying again, and keeping them in the cheapest option, IKEA bookcases each called Billy, till I realized how unsuitable and heavy these particle-board monsters really are. You wouldn’t bury your worst enemy in a coffin that plain. I won’t call them ugly, but a pig is still a pig, however pretty the lipstick you may try to apply; no matter how precious the books you want to display. So I’ve been giving those Billys away to The Central Aid Furniture project, which offers them to its low-income customers.

That was the easy part. What to replace them with? I’ve scoured the world-wide web for ready-mades on sale or even pictures of what I sought. There are plenty of zany ideas, but I found none which truly respected their function, none which had a notion of the elegance possible. I even checked out bookshelfporn.com. Surely there’d be something there? But alas, Freud was right. Mankind is polymorphously perverse: that site drools over quantity with a dreary monotony. The truly erotic must have more finesse. Bookshelves are to books what clothing is to the naked human form. The one should draw you to the possibilities of the other.

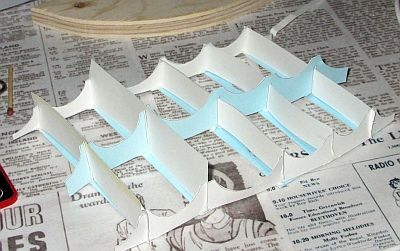

So I had to design my own, from first principles. I’ve just completed Mark 5, the most advanced. The whole process, from design to model, from cutting to assembly, has been a major project. Mark 5 is based around a central spine or keel, as in a wooden ship from the long era of sail. One day I might add several layers of yacht varnish, but it’ll do as it is. And I hope when I’m gone the next house-owner will keep it there intact.

The 12mm spruce plywood from which it’s built is rather soft, but surprisingly light. One thinks of Howard Hughes’ famous “Spruce Goose”, that huge flying boat which flew only once and became a museum piece in Long Beach California, where I missed going to see it for some reason when I went there in 1989, and lodged in the RMS Queen Mary. The plane is actually made of birch, and has been moved to another museum in Oregon.

And here I must digress and say how similar was the fate of the Saunders-Roe Princess, built in East Cowes, where I briefly lived with stepfather no. 2 who worked for that company. See this post. And again, how similar was the fate of the R100 airship, not to be confused with the ill-fated R101, which I wrote about in this more recent post.

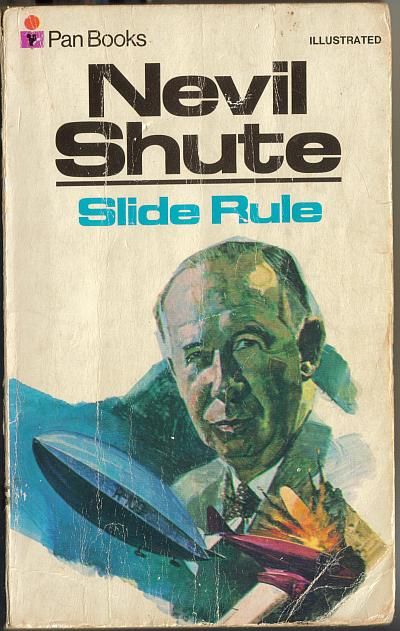

I’m glad in particular to speak again of Nevil Shute’s book Slide Rule, which describes his role in the construction of R100, because I thought of it during the design and construction of my bookshelf. Would its lightweight elegance be robust enough to bear the weight of Harrap’s French & English Dictionary, & various coffee-table books we’d been given that you can hardly pick up? In the end, I may have over-engineered it, to be on the safe side, but I don’t think it shows.

Here’s another passage from his book, the gist of which stays in my memory from reading it more than twenty years ago:

Sixteen steel cables ran from the centre of the polygon, the axis of the ship, to the corner points, bracing the polygonal girder against deflections. All loads, whether of gas lift, weights carried on the frame, or shear wire reactions, were applied to corner points of the polygon, and except in the case of the ship turning these loads were symmetrical port and starboard. One half of the transverse frame, therefore, divided by a vertical plane passing through the axis of the ship, consisted of an encastré arched rib with ends free to slide towards each other, and this arched rib was braced by eight radial wires, some of which would go slack through the deflection of the arched rib under the applied loads. Normally four or five wires would remain in tension, and for the first approximation the slack wires would be guessed. The forces and bending moments in the members could then be calculated by the solution of a lengthy simultaneous equation containing up to seven unknown quantities; this work usually occupied two [human!] calculators about a week, using a Fuller slide rule and working in pairs to check for arithmetical mistakes. In the solution it was usual to find a compression force in one or two or the radial wires; the whole process then had to be begun again using a different selection of wires.(6)

There is more in the same vein, but the above is enough, or more than. In my case, I’ve been aware that the bookshelf’s load is spread in a fashion I prefer to call “unquantifiable”; balanced and cantilevered in myriad ways. It seems rigid enough: you don’t see it flex or hear it creaking, and I don’t suppose it would fall off the wall in an earthquake.

There is a satisfaction in engineering, even on the miniature scale I’m capable of. Let Nevil Shute, though, have the last word.

When all forces were found to be in balance, and when all deflections proved to be in correspondence with the forces elongating the members, then we knew that we had reached the truth.

As I say, it produced a satisfaction almost amounting to a religious experience. After literally months of labour, having filled perhaps fifty foolscap sheets with closely pencilled figures, after many disappointments and heartaches, the truth stood revealed, real and perfect, and unquestionable; the very truth. It did one good; one was the better for the experience. It struck me at the time that those who built the great arches of the English cathedrals in mediaeval times must have known something of our mathematics, and perhaps passed through the same experience, and I have wondered if Freemasonry has anything to do with this.*

In my own case, I have been consciously building shrines of spruce in thanksgiving to a host of authors for their generosity in sharing “what oft was thought, but ne’er so well express’d”, and thus to be mirrors to the reader’s soul.

PS 29th July 2018: The original post started with talking about reading and writing, with quotes from more than one author. I’ve separated that part and republished it as a post on its ow. I’ve split the comments as well.

* From pp 72-73 of Slide Rule, by Nevil Shute (Pan Books, 1968)

An elegant design.

LikeLike

Brilliant! This post has me intrigued for many reasons, not the least of which is your sense of design and carpentry skills.

One of your best IMHO.

LikeLike

Glad you like it. The design took many days. It was Monty (see previous post “The Happy Ending”) who introduced me to carpentry, about 65 years ago, but these are the biggest jobs I've done since.

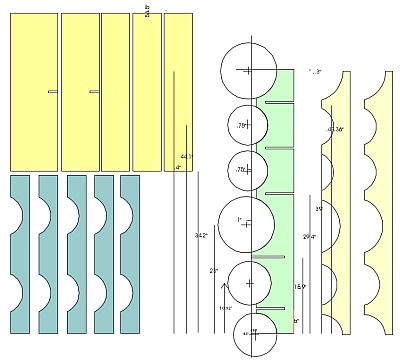

I've added another photo, showing my helper building Mark 3. William has worked with me on a succession of jobs, each one requiring more skill than the previous one. Whenever I teach him something new, he gets it quickly and soon surpasses me in deftness, speed and anticipation. But it's more exhausting with an apprentice, faster-paced, fewer rests. We built Mark 3 in two days not counting the coats of varnish. Mark 5 was a bigger job but the design and build was staggered over a month. And the build was facilitated by the timber yard, who for £10 did 19 straight cuts so that the piece of plywood was divided into the 13 pieces you see in the top diagram. I only had to saw out the arcs, the central shelf cutouts and final cutting-to size to fit the alcove.

Someone younger than I could start a business, I'm sure, making these things. But they'd need more automated tools. They take far too long by hand-crafting methods.

LikeLike

“Bookshelves are to books what clothing is to the naked human form. The one should draw you to the possibilities of the other.”

Now there's a quote for the ages.

LikeLike

Bryan, I hope you are wrong! Taken literally & out of context, it’s a whoremongering thing to say. Let it stand where it is, screwed down within its paragraph, like a stool in a bar that don’t want no more trouble.

Anyhow, wasn't it you or DaRev (in blessed memory—he's been on a vow of silence rather long) who pointed me in the first place to bookshelfporn.com? I have to pin the blame on someone.

LikeLike

Even when one is committed to one’s inner life, and all that that means, there is nevertheless something intensely satisfying in ‘getting something done’ in a practical way. Your bookcases, I’m sure, gave you just that kind of satisfaction of a job well done.

Going back to your opening paragraphs, I certainly feel for you when you talk about expressing something perfectly in the head, only to lose it when needed. And sometimes it seems a cause for regret when I look back over some of the things I have written, and ask myself, “Did I really write that?” in a manner that expresses uplifting surprise. Of course the follow-up is, “I’m sure I’ve passed my peak, and will never be able to write like that again.”

There is a joy about reading what others have said, that exactly expresses what one would have wanted to say. In the end, it isn’t so much what one records as what one experiences that counts. It’s just that for some people, the veil that hangs between, and distorts, the experience as it passes into a recording, seems to be thinner than for me at least.

I did enjoy this post very much, and well done for the carpentry efforts. You have my admiration for your work.

Even when one is committed to one’s inner life, and all that that means, there is nevertheless something intensely satisfying in getting something done in a practical way. Your bookcases, I’m sure, gave you just that kind of satisfaction of a job well done.

I did enjoy this post very much, and well done for the carpentry efforts. You have my admiration for your work.

LikeLike

You might be interested in another quote from the same book by Arendt (The Human Condition, p225) , which I find relevant to what we may call “Zen in the art of bookshelf construction”:“It is indeed true—and Plato, who had taken the key word of his philosophy, the term “idea,” from experiences in the realm of fabrication, must have been the first to notice it—that the division between knowing and doing, so alien to the realm of action, whose validity and meaningfulness are destroyed the moment thought and action part company, is an everyday experience in fabrication, whose processes obviously fall into two parts: first, perceiving the shape (eidos) of the product-to-be, and then organizing the means and starting the execution.”Wow, that Hannah Arendt, some dame! (They’ve made a pretty good film in her name, too.)

LikeLike

[…] Green https://rochereau.wordpress.com/2015/03/24/the-bench-on-st-michaels-green/ Spruce https://rochereau.wordpress.com/2015/03/19/spruce/ Why did the R101 Crash? https://rochereau.wordpress.com/2015/01/29/why-did-the-r101-crash/ Sisyphus […]

LikeLike

[…] this post, I described how I’d got rid of the IKEA bookshelves and replaced them with my hand-built […]

LikeLike