I spent days trying to compose a sequel to my last post about Maggie Boden’s book, The Creative Mind. She had outlined a science of creativity, leaning on her expertise in Computational Psychology, which she more or less invented. A learned paper says ‘Computational psychologists are “theorists who draw on the concepts of computer science in formulating theories about what the mind is and how it works” (Boden, 1988, p. 225)’. I got carried away with the idea of taking it a step further & sketching out a science of subjectivity, despite the fact that this genre of human experience (which Boden calls “idiosyncratic representations of the world”) is specifically excluded from Western science.

I thought that religion, for example, could be explained sympathetically in neutral terms as opposed to its own self-referential doctrines, which can often be distilled into “The Bible (Koran, etc) is the Word of God because it declares itself as such.” And then we would turn our swords into plowshares, & live happily ever after. I thought that a science of subjectivity could discover that the feeling of being blessed by a heavenly presence is traceable to such-and-such stimulation of the brain visible on a neurologist’s monitor screen, identical to a stimulation which occurs equally in people with no religious beliefs at all. . . . So then everyone would join hands and sing Kumbaya together, realizing there is nothing left to fight about.

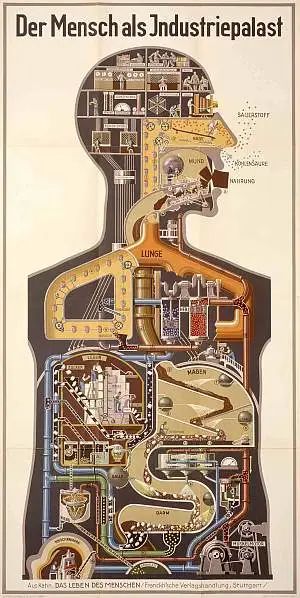

I rather liked the illustration I dug up, though. It’s one I’ve used before, but it’s even better when you click on it and watch the animated version. See also this document. The original poster was designed by Fritz Kahn, who illustrated a book I owned as a child: The Secret of Life: the human machine and how it works. Human machine, yes; secret of life, no.

Anyhow, the post I laboured on destroyed itself through excessive editing. Instead of grieving its loss I felt instantly liberated, and glad of the timely lesson it bequeathed.

I enjoyed the brilliance of Maggie Boden’s book, The Creative Mind to the point of envy, especially and illogically since I’d met her face to face, near the beginning of her illustrious career. I wrote, in that unlamented draft, how much it had taught me about creativity.* Well, perhaps. Writing down your spontaneous thoughts lets you question them later, especially when you’ve let yourself get carried away. Until the counter-thought blows down the fragile house of cards, you’ve taken time out to live another life in harmless imagination, explore it all the way to reductio ad absurdum. Then you wake up in the middle of the night as if it had all been a dream.

Actually I prefer Henri Bergson’s Creative Evolution (1907), though I’m only 3% through and feel no obligation to persevere to the end. Enough with idol-worship! He proposes “an alternative explanation for Darwin’s mechanism of evolution”, one which is generally considered to have been superseded by the “neo-Darwinian synthesis”. I’m no scientist. I have no grounds to argue with their verdict on Bergson, nor on any aspect of their work. They don’t impinge on my home territory, so to speak.

What I embrace is that which speaks to me and finds an answering response within, beyond fact and reason. Bergson, regardless of how he is seen today, speaks a language I understand better than Boden’s. “Bergson convinced many thinkers that the processes of immediate experience and intuition are more significant than abstract rationalism and science for understanding reality.” (When lacking other attribution, my quotes usually come from Wikipedia.) And here’s a tiny excerpt from his book (he uses many words where I would prefer to use few). It makes sense to me, though a scientist may say it explains nothing, means nothing:

The universe endures. The more we study the nature of time, the more we shall comprehend that duration means invention, the creation of forms, the continual elaboration of the absolutely new.

This chimes with things I’ve tried to say since this blog began. I’d like to finish with the first paragraph retrieved from the unlamented draft which destroyed itself some hours ago:

This blog has always been dedicated to fleeting impressions that defy description or analysis. An early example was a brief moment of what I called knowing, on a rough-and-ready street near my home, when I saw something special in all the people I encountered there, which I hoped they would feel themselves, though suspecting they didn’t. I didn’t know how to express it, unless by using the word “immortality”. (See this post.) It was a powerful experience and I did my clumsy best to convey it at that time. Another kind of fleeting experience comes with a phrase that sums it up, seeming to arrive in my head newly-minted like a whisper from the Muse, but needing reflection and expansion to tease out its meaning. An example which springs to mind is in a post titled “Infinite are the depths” for that was the phrase which accompanied the moment of insight, that went beyond ordinary consciousness.

* I tried to convince myself that I felt positive about Maggie Boden, especially as I was trying to make contact with her and see if she remembered the occasion. There was no reply to my email. Much later I allowed myself to remember the experience of meeting her: an instant mutual antipathy. She more or less cut me dead though we were staying in the same youth hostel. When she proposed that everyone play Scrabble, which I thus heard of for the first time, I retired to my bunk and slept. I don’t think we ever spoke to one another. One prefers to repress such memories of gaucherie & low self-esteem.

Not only that, but I very much dislike her determined blindness to what makes us human. And I’m ashamed to recall how I was prepared to deny all this for the sake of contact with a respected scientist / celebrity.

It is late in the day, and my bed is calling. But I must say something, even if it is that I cannot find a way into this post because at first glance it appears to be self-contained, it requires no comment. Yet comment I must, because I am always excited by expressions of wisdom, and writing that generates questions. I think Socrates and Plato had much to say about this. So I will ask, as an opening gambit, one simple question. How do you define 'machine'? And now to bed.

LikeLike

It is early in the morning, and your question is so excellent, Tom, that I feel challenged to deliver an answer that may be worthy of it. “Machine” is a potent word in science and technology; equally so in everyday mythology, that is in the language of metaphor.

Literally a machine is a human artefact, constructed to deliver a useful outcome. Traditionally, its usefulness is measured by its predictability: it does what it’s meant to do. A computer program which doesn’t do this is a malfunctioning machine, just like a chisel or lathe which spoils the wood presented to it.

So when Boden embarks on computational psychology, and ends up with computational models which she claims emulate human creative processes, she is discovering mechanical aspects of creativity. To use her favourite example, the imagery employed by Coleridge in his “Ancient Mariner” can be traced back to things he read elsewhere, and other influences. Which doesn’t mean that his writing of the poem could have been predicted from antecedent inputs.

Common perception tells us that life is not predictable. “Life” is also a potent word in science and technology, when compared with inert matter. Bergson likes to make a distinction between objects of investigation whose behaviour may be predicted—mechanical things obedient to determinable laws—and life, which unfolds unpredictably in time.

The central paradox is this, that physically, I can be shown by science to be made of machine-like components, whose construction and behaviour is semi-predictable by DNA, which had not been discovered in Bergson’s lifetime. Nor had Chaos Theory, come to that.

But . . .

(I shall leave the rest hanging and unfinished, an unpredictable work-in-progress)

LikeLike

“I thought that a science of subjectivity could discover that the feeling of being blessed by a heavenly presence is traceable to such-and-such stimulation of the brain visible on a neurologist’s monitor screen.”

I believe there have been experiments done to that effect.

And hey, don't go switching book horses in mid-stream on me. I'm still working on the Boden book. So far it seems interesting, although “so far” isn't too far at all yet. It's squeezed somewhere in the pile of all my other daily diversions.

LikeLike

Also, as long as this post is sprouting branches (or maybe eyes like a potato) right under my feet, I might as well take a stab at this “machine” question.

Yes, “machine” can refer to a human artifact, but I think in the broader sense that it's being used here and the connotation involved, it would be closer to say that a machine is anything that operates through complex functions; a thing with many working parts.

LikeLike

I'm mindful of what you say, Bryan. Bergson is too heavy a dude to add to anyone's daily reading list or to-do list of chores. I did download his book to my Kindle, but in this post I just used the reference from laziness, as any dwarf would do, given the opportunity to thumb a ride on shoulders of giants.

And as you say, there have probably been experiments done to that effect, just as ZACL says, there are branches of science doing anything I might dream about.

So, to quote Brutus, let them

“bestride the narrow world

Like a Colossus, and we petty men

Walk under [their] huge legs and peep about . . . “

LikeLike

So according to your definition of machine, Bryan, I cannot escape being one. For I am a thing with many parts, most of them still working, I'm proud to announce. Therefore I am a machine, and my case is destroyed. Are we having one of those bar-room fights again? I do hope not.

LikeLike

A fight? No. Not that I'm aware of. I was just trying to field Tom's question.

But I can certainly appreciate why you might balk and being referred to as a mere “machine.” In that regard, one might say that you are more than the sum of your working parts. The body has its mechanisms (as does the mind, I'm sure) and as such a human being might be said to be a “machine”, but I would hardly think that it would do justice to the human experience to close the book there and call it the end of the story. What more is there to the story? Who can rightly say? I know I can't, at least not off the top of my head. For now, I'll just say that I have my own misgivings about such a reduction, just as you do.

LikeLike

Yes, and we have in the past discussed the old argument about free-will and determinism. I've always thought there was something wrong in the premise of that argument. At this moment, it seems obvious that “free-will” is not the opposite of “determinism”. What is not determined is indeterminate. It's open. Che sera sera, the future's not ours to see, what will be will be. Thus spake the philosopher Doris Day.

LikeLike

Sorry for the facetiousness in general and silly reference to bar-room fights in particular. I meant that I still regret the discussions which scuppered our project “Stranger in Paradox”, for which I still acknowledge full blame. As we have oft remarked, you can't edit blogger comments, only delete them.

LikeLike

Okay! So let us accept that our sensual bodies are machines of the biochemical variety, constructed in a biochemical machine-shop. This then leads us to the question, “What is the 'I' to which you referred when you said that you were not a machine?” Clearly, the 'I' does not refer to the physical/sensual body whose CPU creates the delusion of reality, and then proceeds to objectify that delusion.

It has been claimed, by Gurdjieff and others, that the 'I' is unknowable at least by science and debate which requires the use of an ego-based thinking function. Certainly it would appear to be unknowable through the senses and the intellect, a point that Plato made. Because the 'I' is thus indefinable, relating as it does to our inner rather than our outer world, it and its experiences cannot adequately be put into words, as you pointed out in the final paragraph of your script. Yet in that moment, you 'experienced.' That experience was reality, truth, a 'knowing' as perceived by your 'I-ness'.

I agree with your statement that, “What I embrace is that which speaks to me and finds an answering response within, beyond fact and reason.” I come back to the point I made in my first comment that your post had the air of self-containment. I think that was because through your description of the writings of others, your own experiences of reality were permeating, and I enjoyed that.

Finally, I would like to thank you for this opportunity to engage in a sharing, rather than a debating, of ideas. It has been some time now since I wrote on Gwynt, quite simply because I feel lost, and fear to tread where angels will not. I don't know how long this phase will last, but living with it is not easy.

LikeLike

I can’t quite proceed as fast as you suggest, Tom, when you say “Let us accept that our our sensual bodies are machines of the biochemical variety, constructed in a biochemical machine-shop.” I don’t feel justified in accepting this as an axiom to start from, insofar that a machine, in my definition, behaves predictably except when it malfunctions. Unlike you and me.

I would want to leave open the possibility that you and I make ourselves up as we go along, to some extent; I don’t mean by a conscious act of will, though that is not ruled out either. Let us suppose that the behaviour of a living creature, including maintenance of its own physical form, is determined by interaction between its nature and the surrounding world, moment to moment. This makes us different from machines, which would be uncontrollable if they behaved like that—as has been much explored in science fiction.

The difficulty I anticipate with Gurdjieff, Plato and others is in establishing cut-off points, frontiers, if you like, separating the “I”, senses, intellect and biochemical machine. Certainly the distinctions exist, but the difficulty is encapsulated in this word “machine”.

“Machine” describes a human concept, like all the axiomatic elements of Euclid’s geometry: lines, points, angles and so on. Do they occur in nature? Not exactly: we see them in nature, by a process of abstraction undertaken by the intellect. Thus we have western medicine which views the person as a machine made up of potentially exchangeable spare parts, which has proven itself successful, according to certain criteria, but not necessarily correct in its understanding of “The Secret of Life”.

LikeLike

A book which has influenced my thinking is 'The Web of Life' by Fritjof Capra. It presents a perspective I find both innovative and compatible with Blake's approach.

Capra:

“At a certain level of complexity a living organism couples structurally not only to its environment but also to itself, and thus brings forth not only an external but also an inner world. In human beings the bringing forth of such an inner world is linked intimately to language, thought and consciousness.”

There is more from Capra in this post:

http://ramhornd.blogspot.com/2013/09/web-of-life-ii.html

LikeLike

Thanks, Ellie. I have not read Capra but see that in “The Web of Life” he talks approvingly of Maturana and Varela and their concept of autopoiesis. I had a book by them which explained that, & in retrospect wonder why I tried so hard to understand it. Now I am happy to leave physics to the physicists, and indeed science of all types to the scientists, especially after the last few days. Bergson is a different matter: a rather endearing philosopher who makes it up as he goes along, and can more easily be seen as wrong now than he could at the time, when DNA had not yet been discovered.

On the topic of Blake I have something for you which you may not have come across: this video made in London showing his grave in Bunhill Fields and discussing his life & works rather well I thought, in just over 6 minutes.

LikeLike

. . . and you will notice that lower down on that page there are several articles on Blake and two more videos.

This one on his radicalism

and this one demonstrating his printing process

LikeLike

“I would want to leave open the possibility that you and I make ourselves up as we go along, to some extent….”

Like existentialism, perhaps? Hmmm? Hmmm!?

LikeLike

I don't think so . . . not Sartre, not Kierkegaard, not Camus. Who or what do you have in mind?

No, it was something akin to chaos theory, in the sense that in the wide world, as opposed to a machine working in strictly controlled laboratory conditions, it is impossible to know what might happen and what what will actually happen. I think we can predict with some certainty what won't happen. A piglet won't be born which grows wings and learns to fly. The Pope won't convert to Islam.

I happened this evening to see a Martini ad on YouTube, called Luck is an Attitude which illustrates the point about making ourselves up as we go along . . .

LikeLike

This is what is so exciting to me: to see the evidence of people working to build the intellectual and spiritual content which is the foundation of our civilization. Thanks for all three videos and for the confirmation that the minds of men are being opened by our popular media.

Capra postulates transitional points where the organization can change its dynamic. The same elements are present but the energy is redirected to produce a different outcome. The simplest example of this to me is learning to read: the same marks are on the page but how different is their import. That was what Blake was always seeking: to see the world in a grain of sand, to see that everything was interconnected and holy, to hold infinity in the palm of his hand.

Perhaps we are moving in the direction of intellect/spirit/art/imagination being dispersed in a interconnected network of humans where no one can claim possession but comprehension is in the shared linkages.

LikeLike

I wasn't really thinking of a specific person, just that general Existentialist idea “existence precedes essence.”

An Existentialist would say, for instance, that a table is a thing (an artefact, if you will) designed to fufill a basic function. Different tables serve different functions. A coffee table serves on function, a breakfast table another, and they are designed with that function in mind. A human being, on the other hand, according to the existentialists, is a work in progress. We exist first and then define our own purpose and fuction THROUGH our existence, contrarywise to how it works with the table. A man becomes a coward, for example, by adopting that way of dealing with life and acting in a cowardly fashion. He doesn't act in a cowardly fashion merely because he was designed to be that TYPE of person, in the same way that a coffee table was designed to be that TYPE of table.

This may be all completely irrelevant to the topic at hand (which I humbly confess has gone a little over my head.) If so, feel free to completely disregard it and continue on as you were.

LikeLike

“Continue as you were” might be difficult. Where were we, anyhow?

Much of it is over my head too. How did we get here? I suggest that the thing which drives us to science, technology, philosophy, politics & theology is the sense that something needs fixing: in particular that others have got it wrong, and that is why there are problems in the world.

What i liked in particular in the videos about Blake that i linked to above is the perspective it gives. He came from a certain class, born in London at a troubled time, with the dark Satanic mills of the industrial revolution near where he lived, and little boys being driven up chimneys to clear the soot. The commentator on one of those videos was saying that all this, and Blake's reaction to it, was very relevant today, because we had riots here in England not so long ago, just as in Blake's day, and our MI6 headquarters is there to spy on us, just as they spied on people then. & my reaction was, “Well there is only a connection there if you see one.”

So when you mention the Existentialist's view, I think of Sartre or Camus. They have been through the ghastliness of WWII, they have abandoned the consolations of religion and need to construct for themselves a new form of consolation that doesn't depend on the old faiths and hierarchies which never protected us from the horrors of the 20th century anyhow.

Today, it's different again. In America you (or they) they see one set of problems. Over here in England it looks different. I say England on purpose because Scotland despite the referendum outcome has created its own new problem, Europe is its own problem, Islam is its own problem, religion has become like a pain in a phantom limb (how can you get rid of that?), everyone's problem is everyone else's problem.

We used to have explanations for everything, and even though they were ignorant explanations they were kind of acceptable or even satisfying if most people subscribed to the same thing. In a war for example, say WWI, it made things more tolerable if one felt that the slaughter was for the sake of something ultimately worthwhile. And we still want to feel that consolation that everything makes sense, so that the world is a sane and safe enough place for us to have children.

So I think that each of us sees it differently but our interest is more than an academic curiosity about different philosophies. It's to see a clear path through the chaos so that everything makes a bit of sense.

And for me, writing this post was a kind of counterblast to my last. That one looked at whether science could throw valuable light on human creativity, and concluded that “Yes, it can.” This one says, in effect, “No, science sees us as machines.” But then I think that people aren't satisfied with that limited role for science. We can't trust our priests any more to tell us about us. So if scientists say something to soften the machine, make it fuzzier & more like us, with quantum physics, or the Tao of Physics (Fritjof Capra) then it gives us hope, which is what we so earnestly desire.

And this is my humble confession of how much is over my head too.

LikeLike

OK, try this on for size:

“But it is only the

inner, unorganized side of a man which can evolve as does a seed by its own growth, from itself.

For that reason the teaching of inner evolution must be so formed that it does not fall solely on the

outer side of a man. It must fall there first, but be capable of penetrating more deeply and

awakening the man himself—the inner, unorganized man. A man evolves internally through his

deeper reflection, not through his outer life−controlled side. He evolves through the spirit of his

individual understanding and by inner consent to what he sees as truth.”

'The New Man'

http://www.innerstream.net/Maurice-Nicoll-The-New-Man.pdf

This is the reason why we struggle to assimilate whatever understanding we can acquire through science, art, philosophy, history, etc. Not because they have the answers but because the answers we have within ourselves may be activated by contact with whatever truth is in them.

LikeLike

From Bergson's thought:

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bergson/#3

“However, a fringe of intuition remains, dormant most of the time yet capable of awakening when certain vital interests are at stake. The role of the philosopher is to seize those rare and discontinuous intuitions in order to support them, then dilate them and connect them to one another… In a word, it is life in its creativity which unifies the simplicity of spirit with the diversity of matter.”

LikeLike

Thanks, Ellie, these are all input to the whole, like disparate jigsaw pieces that turn out to belong to the same puzzle. Watch this space.

LikeLike

Um, guessing from the number of comments here -am assuming that you – or they – are 'machines'.

(a modicum of 'control' by machines, perhaps).

LikeLike

oops, the difference a missing three letters make.

What i meant to type was “you – or they – are NOT machines”.

LikeLike

Thanks for the correction, Davoh, was beginning to think you were speaking in riddles, if not in tongues. There is, it's true, a lot of spam about, kind of machine-generated. Not to mention self-replicating and possibly self-mutating viruses. We need a corresponding modicum of caution. I hope things are sunny in Sunny Corner?

LikeLike