retrieved from my original blog via the Internet Archive

retrieved from my original blog via the Internet Archive

A Los Angeles journalist befriends a homeless Juilliard-trained musician, while looking for a new article for the paper.

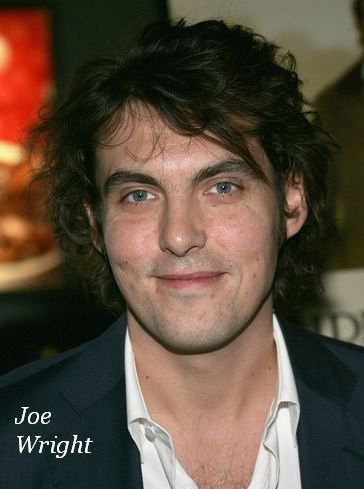

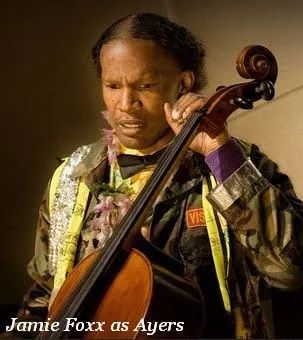

Director: Joe Wright. Writers: Susannah Grant (screenplay), Steve Lopez (book). Stars: Jamie Foxx, Robert Downey Jr. and Catherine Keener.(1)

The film is the The Soloist and I’d never heard of it till Arash wrote a review on his blog.

I liked very much what he said, rented the DVD, and loved it. I’d only query one thing: his reiterated suggestion that the film was less “satisfying” than other films about contemporary madness afflicting a creative person—such as A Beautiful Mind, Shine. I said I would write my own thoughts on the film. I spent a couple of days thinking about it, comparing various films, scribbling a profusion of thoughts, trying to wrap them into a relatively coherent piece, which I accidentally published before it was ready. When I read it through I found it too hopeless to be rescued by editing. There was hardly a sentence worth keeping. The thing was bloated, redundant and dead.

I wondered whether I could rescue anything from the ruins. But then, in the moment of that thought, I received encouragement. The movie itself is about the possibility of rescue from ruins: can the journalist Lopez, through friendship and charitable interventions, save the talented musician Ayers from the ruins of his fallen self?

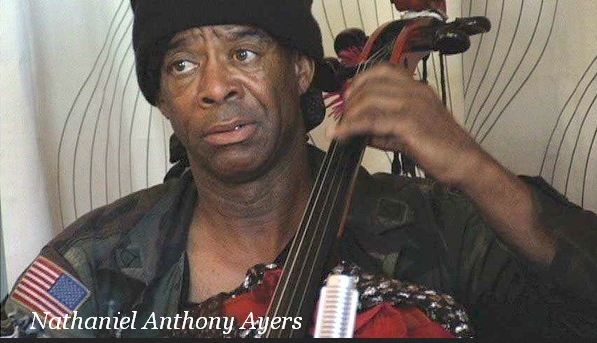

As a boy he’d been accepted into Juilliard, a prestigious school for the performing arts, to study the cello. He could look forward to an orchestral career at least, or even go beyond, like his fellow-student Yo Yo Ma. How did he end up homeless on the street in Los Angeles, bizarrely dressed, getting tunes from a two-stringed violin? Somewhere a fuse must have blown in his head and never got repaired. He hears voices, talks in a logorrhœic stream, has a cleanliness obsession, abhors being shut in, requires boundless personal space and freedom. Many of us have small problems with reality: he has a big problem. If life is a piece of paper, it’s written on two sides. One one is the external world of our senses. On the other, our thoughts and ideas are endlessly scribbled. We all have to reconcile the two sides, whether we’re aware of it or not. But Ayers hears voices, confuses thought with reality. With him, the text of existence bleeds through from one side of the paper to the other, producing an illegible scribble. Thus he finds the world frightening, seeks a niche where he can make sense of it, ends up on the street, a place which offers certain advantages to the mentally fragile. Once there, you’re no longer tormented by the expectations of others; and there’s nowhere further to fall. From all the discomfort, the constant danger of mugging, you can wrest a kind of peace. At any rate, Ayers does.

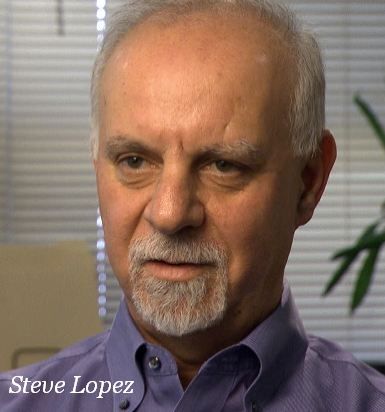

Along comes Steve Lopez, columnist for the LA Times. The chaos in his life is of a different order. His wife threatens to leave him. He’s injured by a fall from his bicycle. He’s driven by a relentless procession of journalistic deadlines. Encountering Ayers in the street, he scents a human-interest story good for several instalments; pursues him in search of material and a back story. He gets unwillingly sucked into genuine friendship and caring; tempted into clumsy interventions on the poor man’s behalf.

When you watch the DVD, a “making of” feature allows you to compare the actors who play Lopez and Ayers with glimpses of their real-life counterparts. This is where you can see for yourself how art triumphs over everyday life. Actors display personality and emotion where real people veil themselves for privacy. I’ve seen documentary re-enactments by the actual characters of real-life dramas*. They’re dull affairs in comparison with The Soloist.

Art is more than feeling. It’s a generous sharing. In an interview the director Joe Wright said:

Art is more than feeling. It’s a generous sharing. In an interview the director Joe Wright said:

I’d never wanted to make a film in Hollywood, I like making films in Britain about the British experience for British audiences. But, I went over there and met Steve Lopez and Nathaniel Ayers (played by Robert Downey, Jr. and Jamie Foxx in the movie), and then the people on skid row, in particular the members of the Lamp Community, and I just fell in love with them.

So, I made it to spend time with them, it wasn’t really a kind of career move.(3)

To produce art takes more than falling in love, but the love must be there. Without love there is nothing but craft, though you could argue that even craft demands love as its magic ingredient. For Lopez, it breathed life into his newspaper articles, spawned a book, inspired his readers, one of whom gave Ayers (still living on the street) a very fine cello. For the actors, it produced performances which change our attitude towards mental illness and homeless people. For Ayers, his love for Beethoven and Lopez sustained his comfortless existence; but hasn’t cured him. The very act of labelling a condition as “illness” implies curability. Perhaps we should say “handicap” in cases like Ayers’, or van Gogh’s, and not mental illness. Handicap can be transmuted to art, and if your life in any way inspires others, that too is art.

Not everyone feels as I do. Says the critic Roger Ebert:

“The Soloist” has all the elements of an uplifting drama, except for the uplift. The story is compelling, the actors are in place, but I was never sure what the filmmakers wanted me to feel about it. (4)

Says Joe Wright:

I tried to respond to the way the story was guiding me. I was also aware that I had to be careful about the ending really, what I was saying. I believe in asking more questions than I answer, to leave the audience with questions, and not to suggest there is any simple cure for the situation. (3)

I’m with Joe! Art is more than life. It is a mirror to show us what we cannot see unaided. Without reading, without movies, without life surrounding me doing its thing, without writing, I’d have a poorer idea of who I am. Wilful blindness hides awkward facts from us, but art is the mirror, the candid camera.

Says Michael Foley, referring to Joyce & Proust:

Says Michael Foley, referring to Joyce & Proust:

If you write for yourself, it will be relevant to everyone and if you write for everyone it will be relevant to no-one. . . . In exposing their bizarrely singular natures, these two novelists revealed that psychological peculiarity is universal. No one is as odd as Joyce or Proust—except everyone.

What I dislike most in Hollywood films is their use of cliché as a shorthand to set the scene and present the characters, as if to say, “you know, this kind of person”. It extends to every detail, even the background music, which tells you how and when to feel. It works on me so well that I hate myself, sometimes starting to cry before the opening credits have cleared from the screen, with no element of the plot yet revealed, just a great panorama, say, and an orchestra spinning the first golden threads of joy mixed with doom which will permeate the atmosphere till the bleak yet heartfelt finale.

I find no trace of cliché in The Soloist. I may have fought back the tears at one or two points, but I won the struggle easily. Joe Wright didn’t manipulate me, and I bless him for that. Instead of cliché there was freshness. Everything defined itself in fascinating detail. Everything contributed to the story, and the story was compelling for presenting truths validated by your own inner response.

It’s all too easy to peddle platitudes. But then we skim surfaces and in attempting to portray the common truths, miss truth altogether.

I discover myself more in reading than writing. I don’t mean just reading the written word, but maybe studying the false emotions of an actor, reflected in his face, for they are the mirror to feelings I can never directly acknowledge in myself, the distorting mirror that shows me how I really look. When I sit at my desk trying to tell it how it is, words flee. Only when I look elsewhere, sniff the open air, read the book of Nature, catch the phrase someone utters, aloud or in a book, do I collect clues to define my true state. Like Dirk Gently, the holistic detective, I can’t help believing in the interconnectedness of all things.

I discover myself more in reading than writing. I don’t mean just reading the written word, but maybe studying the false emotions of an actor, reflected in his face, for they are the mirror to feelings I can never directly acknowledge in myself, the distorting mirror that shows me how I really look. When I sit at my desk trying to tell it how it is, words flee. Only when I look elsewhere, sniff the open air, read the book of Nature, catch the phrase someone utters, aloud or in a book, do I collect clues to define my true state. Like Dirk Gently, the holistic detective, I can’t help believing in the interconnectedness of all things.

And the more I explore through reading and writing, the more fractured I find myself to be, the more handicapped, the more human. Pessoa is the Portuguese for person. Let him have the last word here, possibly to shed light on the mind of Nathaniel Ayers:

Nothing is more oppressive than the affection of others—not even the hatred of others, since hatred is at least more intermittent than affection … But hatred as well as love is oppressive; both seek to pursue us, won’t leave us alone.

. . .

Only what we dream is what we truly are, because all the rest, having been realized, belongs to the world and to everyone. If I were to realize a dream I’d be jealous, for it would have betrayed me by allowing itself to be realized…. We achieve nothing. Life hurls us like a stone, and we sail through the air saying “Look at me move.”