What makes us the way we are? What sets us off on our own unique path? Heedless of a fine drizzle, I set out on foot to West Vale, pondering on these questions. There is nothing like walking to set imagination and memory alive. On this afternoon of purposeless wayfaring, I saw my whole life stretched out as a consistent whole. So on the way, I composed an autobiographical memoir, keeping to the theme of “Going it alone”.

I spent my early childhood in Bassendean, a suburb by the Swan River in Perth, Australia. We lived in a bungalow on the old Perth Road. I wasn’t a spoilt child: my mother would leave me there sometimes when the landlady or other lodger offered to keep an eye on me. I was once left unattended in a playpen on the verandah. She was shocked on her return to find not just me missing, but the playpen too. I was found toddling along the pavement, still in the playpen, pushing it straight towards the riverbank.*

When the war ended, my newly-widowed mother yearned for England. I adored the happy-go-lucky life of Bassendean, but for her it had been a makeshift. She was a cut above: her family coat of arms was in Burke’s Landed Gentry. Soon after my fourth birthday, we set sail on the mv Rangitata bound for Tilbury. As the ropes were cast off at Fremantle, the passengers stood on deck waving to loved ones left behind on the quay. Mother never told me that my real father was amongst those seeing us off. I had not been told about fathers, though I may have picked up some information from children in the street.

On this ship I escaped from my mother at every opportunity. I explored the ship from top to bottom and bow to stern, wriggling unimpeded through doors and up ladders. The crew usually chased me away from their deck, but I got kindness and care from a thousand mother-substitutes. The ship was full of war brides emigrating to join their fiancés. After six weeks on board, I remembered no other life, but it came to an abrupt end at Tilbury.

This return to England, with its bombsites and scarcity, proved a shock to my mother. Even her parents’ house had been bombed. She’d spent the Thirties in Singapore as a dancing teacher, with cooks and maids and chauffeurs and Chinese millionaire clients and a tall, dark handsome husband. Possessions, husband and way of life had all been wiped out by the Japanese invasion. She had escaped with her life – and her little bastard from Bassendean.

After the winter of ’47 with deep snow and no heating in my grandparents’ half-bombed house, she had the bright idea of finding a wealthy husband in Switzerland. On the way, I was dropped off to lodge with my “aunt” in Holland. Auntie Non had two little babies of her own, so I – cuckoo in the nest – was shut out of the house on fine days to fend for myself, hours at a time. I explored the woods and picked bilberries. I saw blood and feathers left by foxes after raiding chicken runs. I saw sacks of grain being pulleyed up to tall storehouses at the wharves. I found a fascinating field strewn with tiny pieces of metal and – my favourite – fragments of mirrors. We lived at Arnhem, so perhaps it was part of the battlefield where so many Allied parachutists had died.

I went off on my own to school each day, with a little tin of jam sandwiches for lunch. I dodged the big barking dogs and lingered at the smithy, where the furnace roared. I winced when the smith burned in a new shoe on the horse’s hoof and hammered in the nails. My Dutch became fluent. Once again, my previous life faded like a dream.

One day my mother turned up to collect me for the return trip to England. Whenever I got used to a life, I was dragged away to something else. Less than a year previously, I had successfully learned from a Victorian primer, Reading Without Tears, at my grandmother’s knee. Now I could read in Dutch too but when I tried to speak English, Dutch came out. For many months, my “aunt” sent me books from Holland, but soon I could not read them any more. Another disconnected episode of my life faded away.

Back in England, my mother started seeing a gentleman in the next town. Things became serious, and one day I was invited over to meet him for tea. I suppose she was already installed in his house, but I did not keep track of her comings and goings. All I remember is my grandfather putting me on a bus, with instructions to get off at West Hill. Unfortunately there were West Hills in both towns and I got off at the wrong one, then wandered around feeling foolish until my grandfather found me hours later.

It was just after my sixth birthday when I acquired a stepfather. Then my mother acquired a baby. In principle, this was the start of normal family life, but I was sent to a boarding school seven miles away, giving space to the newly-weds, I guess. At half-terms I came home by bus. Once I found the door locked and no one at home: they had forgotten I was coming.

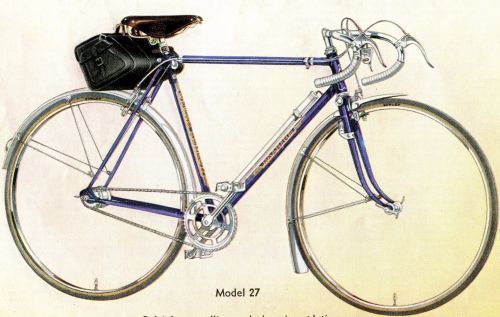

My happiest school memory was when I was ten. My parents told the school I could not come home at half-term. I did not know it yet but my mother had finally walked out and gone back to my grandparents’ house pending divorce. A fellow pupil, his name was Cooksey, lent me his bicycle at half-term. I had never ridden a bike, but I spent every waking moment of those two days on a stony track through the woods. Bruised, bramble-scratched and nettle-stung, I dropped into bed exhausted when it got dark. My dream was all of bicycle-riding.

My happiest school memory was when I was ten. My parents told the school I could not come home at half-term. I did not know it yet but my mother had finally walked out and gone back to my grandparents’ house pending divorce. A fellow pupil, his name was Cooksey, lent me his bicycle at half-term. I had never ridden a bike, but I spent every waking moment of those two days on a stony track through the woods. Bruised, bramble-scratched and nettle-stung, I dropped into bed exhausted when it got dark. My dream was all of bicycle-riding.

At dawn I leapt up and back into the saddle, still sore from the day before. Astonished, I found that I could ride steady and fast without falling off. Boy and bicycle, joy and triumph, all alone in the woods.

I realised something then, and kept it a guilty secret till this present moment. I loved books more than people and riding a bike more than my parents.

*PS on October 18th 2025: now in my eighties and with a spinal condition, I can walk plenty each day propped up on a Topro walker, supplied by the NHS.