It took little time for my mother and stepfather to discover their marriage was a mistake. The knot was tied in church on a chilly day in January: my sister appeared in September. He was a bachelor of independent means—owning various properties around the town and living off their rents, while she was a woman of the upper middle-class with a young bastard to support. At thirty-eight she was a little old to live indefinitely with Mummy and Daddy, especially as her younger sister, Mark’s mother (see my last) had already sought sanctuary there, in similar circumstances.

Perhaps bride and groom each thought the other a prize because of their looks. My mother was not Helen of Troy but she knew how to turn men’s heads: a natural blonde with the heart of a spoilt child. He—I must give him a name, for he was the first and not my only stepfather. I’ll call him Kenneth: it suits the way he spoke, stuttering like a bashful boy. You would not meet a more painfully shy man aged fifty-two. Yet he was handsome. Not as tall as my mother’s first husband, that long limbed-Dutchman with the moody looks of Rudolph Valentino, he was “rangy” all the same. With his lean physique & rugged yet boyish face, he could have modelled for country tweeds and brogues. But the state of undress suited him most. He was a dedicated naturist. If you don’t know what that is, “all will be revealed”: a phrase that may be all the clue you need. Far from being just his oddity, naturism affected the course of my life, as I will show in a future instalment.

I have never seen a white man with such mahogany skin. At school there was a wall-map of The World, in varnished calico, showing the Empire in pink, with the various “races” around the edge, in their national costumes. The Red Indian was depicted with a skin the same colour as Kenneth’s. To him it was a sin to stay in when the sun peeped out; and even when it wasn’t shining, indoors was stuffy whilst outdoors was bracing. He was so lean and fit you could see his muscles and veins, visible like tangled ropes under a wrinkled hide.

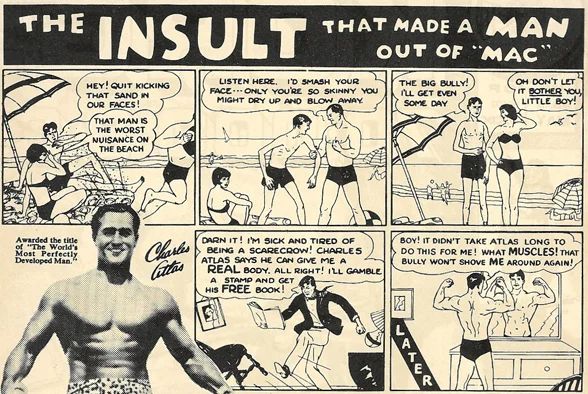

Kenneth had been like the classic “seven-stone weakling” in the advertisements of Charles Atlas. He’d been a runt of a child, prone to illness, his lungs judged defective. He was bullied at school, overprotected by womenfolk at home who enforced lots of bed-rest and no playing out with other boys. As he emerged from his teens, a doctor advised him that all this molly-coddling had been bad for him: he should strengthen his body with fresh air and hard work. An inheritance gave him the chance to buy some land and start a pig-farm, all on his own. He prospered and converted his capital into properties to let. He could not abandon the thrift which had helped his lonely path. He obeyed a puritanical Christianity and Victorian values, but his true religion was Nature Cure. Stanley Lief, Harry Benjamin, Gayelord Hauser were its High Priests, with their respective publications Health for All (a magazine), Better Sight without Glasses and Look Younger, Live Longer.

Kenneth had been like the classic “seven-stone weakling” in the advertisements of Charles Atlas. He’d been a runt of a child, prone to illness, his lungs judged defective. He was bullied at school, overprotected by womenfolk at home who enforced lots of bed-rest and no playing out with other boys. As he emerged from his teens, a doctor advised him that all this molly-coddling had been bad for him: he should strengthen his body with fresh air and hard work. An inheritance gave him the chance to buy some land and start a pig-farm, all on his own. He prospered and converted his capital into properties to let. He could not abandon the thrift which had helped his lonely path. He obeyed a puritanical Christianity and Victorian values, but his true religion was Nature Cure. Stanley Lief, Harry Benjamin, Gayelord Hauser were its High Priests, with their respective publications Health for All (a magazine), Better Sight without Glasses and Look Younger, Live Longer.

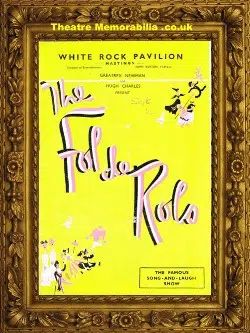

For recreation, he liked to see variety shows at the White Rock Pavilion, such as the Fol-de Rols”. For old times’ sake—he clung to every habit that had yielded him joy—he haunted the livestock market at the nearby village of Battle. We’d all lean over the pens whilst the auctioneer jabbered the bids for calves, sheep, poultry, and pigs, as in Kenneth’s heroic farming days. Then it was time to refresh ourselves in what he called a “tea-place”. He abhorred smoke and drink but loved those places—usually less sunlit and empty than in my picture—where waitresses dressed in black, with white caps and aprons, served tea and cakes.

For recreation, he liked to see variety shows at the White Rock Pavilion, such as the Fol-de Rols”. For old times’ sake—he clung to every habit that had yielded him joy—he haunted the livestock market at the nearby village of Battle. We’d all lean over the pens whilst the auctioneer jabbered the bids for calves, sheep, poultry, and pigs, as in Kenneth’s heroic farming days. Then it was time to refresh ourselves in what he called a “tea-place”. He abhorred smoke and drink but loved those places—usually less sunlit and empty than in my picture—where waitresses dressed in black, with white caps and aprons, served tea and cakes.

I seem to have resembled all three of my mother’s husbands, none of which was my father. Moody like the first, the one I never even knew; awkward in company, restless for the outdoors like the second. Never mind the third, we will get there in due course. But I do recall that in the first days of living in Kenneth’s house—we should call it a flat for the downstairs was let to tenants, in fact I was fourteen before I lived in a house exclusively occupied by my own family—I found myself adopting his stammer. He was my first father-figure. I could hardly help imitating him.

For summer holidays, he favoured a “nudist camp”: Woodside House, Wootton, Isle of Wight. A place which dramatically changed my life, as you may discover.