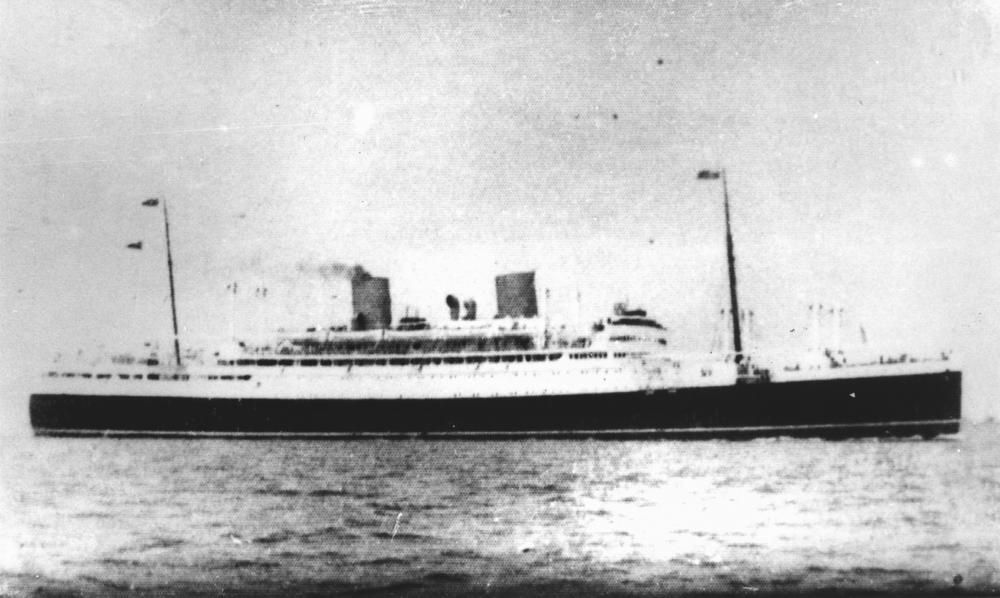

I’m not finished with the mv Rangitata, which brought me as a four-year-old from Fremantle to Tilbury. The Rangitata hasn’t finished with me either. Our acquaintance was a six-week voyage sixty years ago but memories can still be triggered; the shuddering vibration from its engines, the smells of hot paint, engine oil, bleach, disinfectant, sewage. It still haunts my dreams, not as a ship but a labyrinth, a grand staircase at each end and tiers of galleries. I still wander them trying to find my way. Sometimes, I arrive at its second class dining-room, my eyes scanning the crowd for a familiar face, waiting for one person who promised to join me. Through the long corridor of years, the Rangitata is still a theatre of dreams. Not just the ship itself but Fremantle Docks, the scene of an Exodus I didn’t understand. We got up in the night and it was not yet dawn when our taxi arrived at a great looming Customs Shed, in the cold drizzle of an Australian June.

I’m not finished with the mv Rangitata, which brought me as a four-year-old from Fremantle to Tilbury. The Rangitata hasn’t finished with me either. Our acquaintance was a six-week voyage sixty years ago but memories can still be triggered; the shuddering vibration from its engines, the smells of hot paint, engine oil, bleach, disinfectant, sewage. It still haunts my dreams, not as a ship but a labyrinth, a grand staircase at each end and tiers of galleries. I still wander them trying to find my way. Sometimes, I arrive at its second class dining-room, my eyes scanning the crowd for a familiar face, waiting for one person who promised to join me. Through the long corridor of years, the Rangitata is still a theatre of dreams. Not just the ship itself but Fremantle Docks, the scene of an Exodus I didn’t understand. We got up in the night and it was not yet dawn when our taxi arrived at a great looming Customs Shed, in the cold drizzle of an Australian June.

Dream: I’m in a vast shed with a busy concourse and offices leading off. I enter a long bare room, like something out of Kafka, with a counter at the other end and a clerk in attendance. Behind him are pigeon-holes with mail and parcels from many decades ago: faded, dusty, unclaimed. I have been summoned to attend, but my hopes are vague and tattered. The clerk hands me a sheaf of almost illegible papers. Are they for me? No, it is more complicated: something to do with my grandmother; a family secret that no living person understands. My heart quickens. Perhaps I am to inherit something? I wake up and the mystery remains unsolved. I need to know!

Dream: I’m in a vast shed with a busy concourse and offices leading off. I enter a long bare room, like something out of Kafka, with a counter at the other end and a clerk in attendance. Behind him are pigeon-holes with mail and parcels from many decades ago: faded, dusty, unclaimed. I have been summoned to attend, but my hopes are vague and tattered. The clerk hands me a sheaf of almost illegible papers. Are they for me? No, it is more complicated: something to do with my grandmother; a family secret that no living person understands. My heart quickens. Perhaps I am to inherit something? I wake up and the mystery remains unsolved. I need to know!

Memory: the day of embarkation from Australia, Fremantle Docks. My mother is anxious. I tag along, wanting to know what’s happening. She tells me in fragments and I try to make sense of it all. Within that Customs Shed, we go to the luggage office to deposit our trunks for loading into the ship’s hold, but at the time I don’t understand it: only through later overlays of memory. We can stow only small bags in our tiny cabin, which we are to share with two women: the ship is crowded beyond its designated capacity.

The luggage office was hardly memorable in itself, though many incidents of that unique day remain vivid. Its importance came later, when it stuck as the scene of a double betrayal, part of which lurked monstrous and hidden.

As a four-year-old I took comfort in a well-loved soft toy. I would hug it to my chest while my tears soaked into its fabric skin. My favourite one was an elephant. So in our cramped cabin I asked for it and my mother said it was in the trunk stowed in the hold. I could have it when we reached England. I didn’t understand and then she reminded me of that luggage office where we had handed over the trunk.

Our arrival was too exciting to remember the Elephant but I did later, in a moment of tearful need. She confessed to having left it in Australia, along with all my other possessions, bar one: the tattered Monkey with arms hanging off, which was hers when she was a child. My response was a torrent of vituperation surprising from one so small, and long-lasting resentment.

The bigger betrayal was not the Elephant left behind. It was that man left waving at the quayside, of whom I have no memory, for we were never introduced. My father.

Searing. As young children, feelings around a favorite toy are so intense. We have no concept of “symbolism” – maybe partly why we respond to it whole heartedly.

LikeLike

the later part is disturbing. i am quite sensitive to mothers and feel that a mother is the greatest friend of a child.

may be because i have a great mother!

LikeLike

Very touching for someone who have been brought up in the ideal way amidst ideal circumstances. And I quite agree to what ghetu says. In India motherhood is sacrosant.

Its only now with our way of life changing under the strains of new economic order that we can see some variations. Women, in India, were never expected to live for themselves.

LikeLike

[…] I still dream of that voyage […]

LikeLike