(Continued from previous post)

My mother’s beloved Singapore roadhouse was called The Gap: a prophetic name. After the war, it was nothing but a gap; one that she mourned forever and never really replaced.

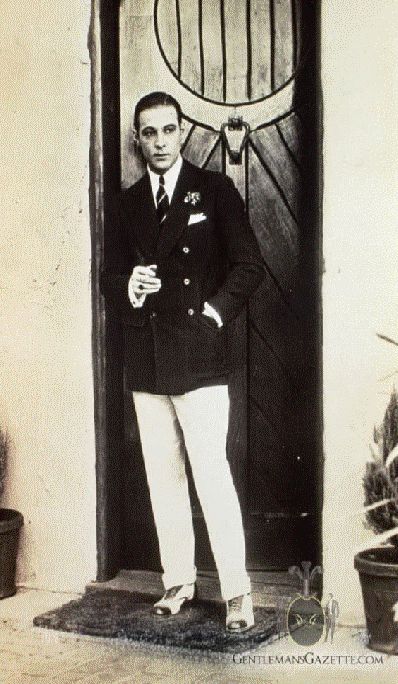

The gap in my life was a father. When I met him fifty years later, he admitted having been in the crowd at Fremantle Docks waving with all the others, while my mother and I leaned over the rail of the mv Rangitata as it receded into the limitless sea. Lucy our landlady was there, I remember her but not him, proof that we were never introduced. Later when I was six, sent to boarding school in England my place of exile and in need of a father to boast about, I was only armed with tales of her husband, missing presumed dead, and photos with his hair slicked back like Rudolph Valentino. I embroidered her tales till my heroic father was drowned saving his best friend Klom, when the boat they were escaping in was shelled by the Japanese. And now I’m wondering if that Klom she spoke of so often was her lover . . .

Throughout my life, I struggled with explaining why and how I was born in Australia, to make it sound logical and not random. “My parents lived in Singapore . . . my mother went to Australia because of the war . . . no, my father was killed fighting the Japanese.” I wonder how many in my generation had to justify our existence like this, never quite clear how we got to be conceived. In the jostling teasing world of boarding school, I tried to tell interesting tales of my life. My favourite invention was a pet kangaroo, which we kept in a high fenced compound, and which I sometimes took for walks on a dog’s lead.

“My father stayed behind doing important war work. No he wasn’t a soldier, he was a radio announcer. He used to read the news. Naturally, that was a cover for his Special Operations on behalf of the Allies, that he couldn’t even tell my mother.”

By the time I learned the facts I was past caring. I went to visit my mother’s best friend who was slowly dying. She’d been kind to me as a child and I’d had an attachment to her daughter, from whom I had learned the facts of life, when she was six and I was four. I said “Let’s do it then!” for I was a smooth operator at that age. We took off our clothes and tried, but it’s not easy standing up. My grandfather caught us and was amused. When I reminded the girl seven years later, she was not.

I digress. My mother’s best friend, croaking with cancer of the throat, managed to whisper that my mother aged thirty had an affair with a boy of eighteen, the result being me. I thought she was fooling, making a joke, though talking hurt her. “I promised your mother never to mention it,” she said, and refused further details.

(To be continued)

whoaw!!!

what a magical tale. it has all the ingredients of a classic post-war novel. please vincent continue till the end. you are a magician!!

LikeLike

Vincent,

You once spoke of being ordinary (or aspiring to it).

I come from a long line of common, ordinary folks each with their own extraordinary tales.

I have found that these stories are often more compelling, and a more truthful reflection of the human experience than those who we would call famous, infamous or celebrity.

We are routinely confronted with trumped up tales of inhuman proportions told on film and in television. And yet tales of the ordinary have so much more redeeming value, with just as much entertainment, excitement, and heart felt response.

LikeLike

i second charles. this is what i always wanted to say. but never had the word power.

LikeLike

Ah, mothers. I have one, too. Who never told me the truth, and couldn't even if she had wanted to.

LikeLike